Armed with Encyclopedic Knowledge

Friday, March 2, 2012

Spears School professors and students develop one-of-a-kind electronic ammunition encyclopedia.

It’s an age-old problem.

How do you get up-to-date information to people scattered across the globe?

With wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, no one deals with that problem more than the U.S. armed forces.

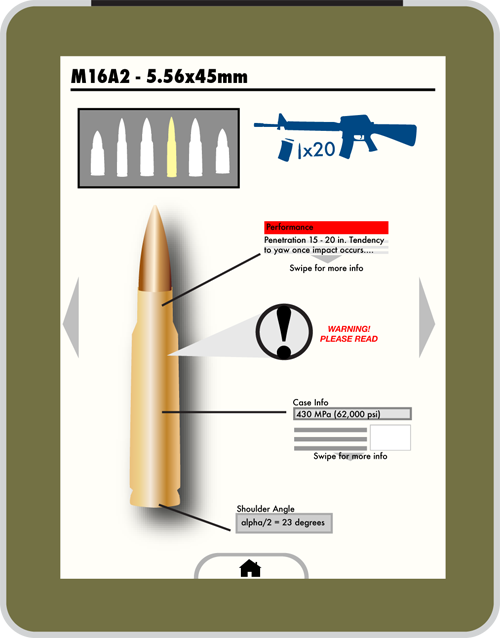

Partnering with the Army’s Defense Ammunition Center, Spears School professors and students developed an electronic ammunition encyclopedia putting the latest information at everyone’s fingertips. Using virtual-reality technology, their products are part of a reach-back system that works on desktop computers to iPods, iPads and iPhones. The encyclopedia is a secure site giving users — largely people who handle, inspect and ship explosives and ammo — details on everything from the smallest bullet to the largest artillery shell.

“Compiling all this into one thing is of significant value,” says Ramesh Sharda, director of the OSU Institute for Research in Information Systems.

It’s the only program of its kind in the American military. The encyclopedia is a support tool for personnel inspecting munitions. It’s also used for refresher training.

and efficiently.

In the corporate world, a good knowledge management system can lower costs and fatten bottom lines. In the Army, it can mean the difference between life and death.

No one knows that better than Upton Shimp, associate director of operations and training at the Defense Ammunition Center in McAlester, Okla. He was working on his doctorate at OSU when he came across Joyce Lucca’s dissertation on a virtual-reality system using 3-D technology to educate employees more effectively than traditional ways.

He spoke with Sharda, who was already working on a project for the Army, a virtual-reality

system to capture organizational memory, the priceless know-how employees’ gather

only through hard-won experience. And Lucca, the dissertation’s author and a postdoctoral

fellow, was one of Sharda’s

graduate students.

“They asked if it could be adapted for training ammunition personnel at a distance,” Sharda says. “I said, ‘That’s a terrific application for that idea.’”

In 2008, he put together a team: Lucca, a slew of talented students and two retired U.S. Air Force officers turned OSU researchers, Lt. Col. David Biros and Maj. Andy Clower.

Working on a more than $1.1 million contract over three years, the group focused on creating the website and server to deliver and house the data. They developed the concept, tested its capabilities and connected it to a Defense Department network.

By December 2008, they had a demo with 10 example munitions ready to show the Defense Ammunition Center, which liked what they saw and green-lighted the program. They wanted 180 items online in two years.

During the summer of 2010, OSU had a little surprise in addition to the demo. Sharda had hired computer science senior and all-around whiz kid Derek Webb to develop a new pitch for the Army: mobile apps for Apple products.

Clower calls Webb a “wunderkind.” If Webb is any example of the kind of students OSU produces, then OSU is surely one of the world’s top universities, Clower says.

Webb is more self-effacing.

“This project totally blew my mind and rocked my world,” Webb says.

The self-described programming addict learned a new computer language, Objective-C,

to develop the applications. He also had to design an interface, an example of which

would be the desktop of a computer or the home screen of

a smartphone.

Everything had to be simple enough for anyone to use in any situation or location. It had to be smooth, reliable and resemble the site his teammates had developed. It also had to be designed without knowing the Army’s security specifications still in development.

“It made our development tricky,” he says.

All that added up to thousands of lines of code and a lot of late nights. Sharda wanted his demo in two months, well before it was ready to be shown to the Army.

“I ended up working very late nights in my apartment in the dark as my girlfriend was trying to sleep, getting mad at me,” Webb says. “I got to see the sunrise a lot.”

He remembers being surprised he was allowed to work on such a project. He only had two years of programming experience at the time. He doesn’t think he could find such work if he weren’t in school.

Webb and a coworker, Fone Pengnate, went through three interface designs before they settled on one.

Throughout the development, Sharda made suggestions and requests to make the app more user friendly. They also worked in a feature that let soldiers erase the device remotely if lost. Eventually, Sharda and Lucca tested the new app and approved it, although it continued to evolve until they showed the Army in the summer of 2010.

Sharda says getting the content was the most challenging part. The OSU team had to track down much of the content on its own. It assembled information and technical data on hundreds of items, taking photos to show damaged and intact items. That was Clower’s and Lucca’s job.

The two were well suited for the job. Lucca has a doctorate in management science information systems and a master’s in telecommunications management. Clower is a former intercontinental ballistic missile launch control officer who spent 24 years in the Air Force, much of that time in an underground bunker with 500 feet of concrete and dirt over his head. He is a grant manager in the school’s management science and information systems department.

“A lot of my background meshed nicely with this project,” Clower says.

Clower and Lucca made 27 trips to McAlester and one trip to Anniston, Ala., to gather data. They took 38,000 photos – more than 100 for each item. They took the photos back to Stillwater, edited them as necessary, such as to show what a damaged item might look like, and put them in the encyclopedia. Clower and Lucca filled out electronic data sheets on the items and developed audio files detailing what users had to inspect. As of August, they had information on 327 items.

Once Defense Ammunition Center users had access, word began spreading among the workers, instructors and students in McAlester.

“We’ve done a pretty good job of covering most of the items that are used by the troops or the ones used in training,” Clower says. “The word on this is spreading. The guys who’ve been through the training the last few years see it, like it and they know it’s there. They’ve started telling the other folks.”

The group is adding more content to the encyclopedia and hoping one day to release the mobile version to soldiers. Sharda says the Defense Department is developing the security guidelines and sorting out how to distribute the program.

In the knowledge management world it’s a rare project — a web-based database-driven system that works seamlessly with mobile devices — and once it becomes more available, it could revolutionize how organizations train their employees.