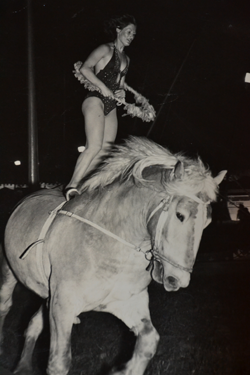

The Big Top show goes on

Monday, February 27, 2012

By Kelly Green

“…I miss a lot of things about show business. When you’re sitting there on the sidelines and somebody rides into the center ring on a horse and does these tricks and is just fantastic and the audience just loves it and the band’s playing, you just can’t help but say, ‘I want to be a part of this.’ I still feel that, even today.” –Robert Rawls, former circus performer

Ever thought of running away and joining the circus? If you live in Oklahoma, you only have to go as far as Hugo to do so.

With a population of approximately 6,000, Hugo, Okla. has a long history of circus culture dating back over 70 years. More than 20 circuses have had winter quarters there. Currently three active circuses headquarter in Hugo: Carson and Barnes, Kelly Miller, and Culpepper & Merriweather. Traveling by road, these tent circuses entertain in towns of various sizes and in small rural communities throughout the country. The owners of Carson and Barnes also own and operate the Endangered Ark Foundation, the second largest Asian elephant sanctuary in the United States.

Led by librarians Tanya Finchum and Juliana Nykolaiszyn, Hugo and its circus legacy are the focus of an oral history research project at Oklahoma State University. The “Big Top” Show Goes On: An Oral History of Occupations Inside and Outside the Circus Tent is comprised of interviews with current and former circus performers living in Hugo. The effort is funded by an Archie Green Fellowship from the Library of Congress’ American Folklife Center. Named for the American folklorist interested in occupations and their cultures, especially those that are disappearing, the fellowships support new documentation and research into the culture and traditions of American workers that will create significant digital archival collections (audio recordings, photographs, motion pictures, field notes) that will be preserved in the American Folklife Center archive and made available to researchers and the public.

“This research is intended to fill a gap in our knowledge about day-to-day work involved with putting on a tent circus,” Nykolaiszyn said. “Preliminary research found very little documented information on this aspect of Oklahoma or on specific people or occupations within the circuses that have had their winter quarters in Hugo. An occasional article in the Daily Oklahoman would mention a Hugo circus with a personal name or two and would refer to Hugo as the Sarasota of the Southwest or the unofficial Circus City, USA.”

Oral history was established as a modern technique for historical documentation in the late 1940s, about the time the first circus wintered in Hugo. Qualitative interviews emphasize the participants’ perspectives and give them a significant hand in shaping the content of the interview. The Oklahoma Oral History Research Program at the OSU Library was established in 2007.

“Circus employees have historically been marginalized and their voices are missing from much of the documented record of occupations,” Finchum said. “As researchers we guide the interview as each participant narrates his or her story. We are seeking to learn and document circus life in relation to circus work.

“What is involved in the typical day of a tight wire walker during the circus season? How does a performer learn the trade? How does a family life coordinate with work in a circus? These are just a few of the questions this project hopes to answer as participants share their first-hand accounts.”

Finchum and Nykolaiszyn traveled to Hugo and met with the Circus City Showmen’s Club, a group of retired and semi-retired circus showmen, to explain the project and recruit potential participants.

Twenty people – nine males and 11 females – shared their experiences and memories of circus work and life. The group represents three families with circus roots at least four generations deep. The majority of those interviewed were trained for the circus by either parents or grandparents. Four of the 20 are first-generation circus workers with an additional one marrying into the business and bringing a parent along. “The circus is not just family entertainment,” Finchum said. “It is families doing the entertaining and all that that entails.” Occupations of participants include: boss canvasman, manager, owner, tight wire walker, aerialist, bareback rider and cook.

As the interviews were transcribed, read and re-read, the researchers say commonalities and differences began to appear. “With each interview it became more evident that over the course of a career in the circus, a single employee may have many job assignments,” Nykolaiszyn said. “For example, as an aerialist ages and can no longer perform in the air, he or she may work the cookhouse and then later the concession stand.”

During one interview, Robert Rawls shared:

“I’ve done just about every job there is to do on a circus, much like the rest of my family. That’s nothing special in my family. If you’re on a circus, you might be a performer, but you also know how to set up a tent, to drive a stake, to operate a truck or a vehicle, or you know how well everything is laid out. You can do the 24-hour man job. You can do it all. We were trained to do everything. So, whenever you’re on a circus, you were always called to do something outside your so-called job description.”

Many of the participants also equated the circus to a small town that moves every day and requires people to live and work in small spaces and in very close proximity.

As shared by Mary Rawls:

“Most of the shows we were on were small and if they weren’t small, then you had a clique of small and they were all friendly. You just felt part of a small town. It was very homey. Everybody knew everybody else and it was just like you lived in a little town that picked up and moved every day. It was very cozy and of course, if you came out with circus slang or something, somebody knew what you were talking about. If you’re talking to a ‘towner’ well, then you’ve got to explain what you’re talking about.”

Statements like Mary’s reflect that although there is very little privacy there is a tight bond among members of the circus community. During the season, the circus may relocate over two hundred times, which means long days and a definite routine. With each “jump” there is order as to which truck arrives first, what each person does at each phase of the set up and take down, and what goes where and when. The researchers found this aspect of the circus has changed very little historically.

One of the unexpected realizations noted by the researchers is the impact regulations have on circuses. Day after day as the circus moves through different jurisdictions, circus management deals with numerous officials. From health inspectors to fire marshals, each town has ordinances for which the circus must comply. In addition to having skills to interact with the paying public, the circus manager needs skills in negotiation, diplomacy, time management and legalese.

The researchers also found that the participants’ identities are closely tied to their work. Circus performers identify themselves as show people, as entertainers. They take great pride in their circus heritage and no matter their age, they can close their eyes and mentally perform.

“With the steady decline of traveling tent circuses, there are fewer and fewer people with first- hand experiences of working in them,” Finchum said. “An end goal of this project is to preserve these narratives for future researchers and to fill in the gap of documented information about this group of the working class.”

This project will also serve to document part of the cultural heritage of southeast Oklahoma and Oklahoma in general. “Circuses that have wintered in Hugo have brought economic benefits to the area as well as entertainment to citizens in the state,” Nykolaiszyn said. “Historically these tent circuses followed the agricultural seasons and set-up on cotton gin lots or ice plant lots. Finding a vacant lot large enough to accommodate a tent circus is becoming more challenging and add the increasing regulations and immigration issues to that, the life of the tent circus is teetering on the edge of an uncertain future.

“Their continued existence is evidence that the circus is still magical for people of all ages and is truly one of the last great family entertainments.”

Original recordings and transcripts from this project will be deposited into the American Folklife Center were they will be archived. Copies will also be deposited into the OSU Library where the transcripts will be made accessible online at www.library.okstate.edu/oralhistory/circus.