Setting the pace

Monday, April 2, 2012

Dr. William Barrow leads veterinary pathobiology team toward a safer, healthier world

When asked what he does for fun, Principal Investigator William Barrow laughs and says, “Work.” The disciplined scientist has had 27 consecutive years of National Institutes of Health funding. Receiving a NIH award is difficult and keeping it is a constant challenge.

Barrow’s infectious disease and organizational background positioned him as a scientist willing, qualified and competent to take on the task of administering a multi-year, multi-million dollar NIH contract such as one he was awarded in 2003. The management and performance of that contract, positioned him and his team well for their newest NIH award.

Currently executing a seven-year IDIQ (Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity) contract with a maximum potential value of $25 million, Barrow’s team at the Oklahoma State University Center for Veterinary Health Sciences is working on making the world a safer, healthier place. Barrow manages the contract and guides the overall performance of the team. The contract continues until May 31, 2018.

The purpose of this contract, Barrow says, is to provide the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) with a broad range of in vitro assay capabilities that can be used to screen potential drugs for human infectious diseases or diseases of human importance caused by infectious agents.

In other words, in a controlled environment, like a test tube, they examine the effects of various compounds to see if they are effective against a panel of bacterial pathogens that are available now or will be available in the future.

“The services provided under this and other similar contracts will assist NIAID in accomplishing its goal of developing medical products to counter emerging, re-emerging and other infectious diseases, as well as agents of bioterrorism,” Barrow says.

His team—all within the Department of Veterinary Pathobiology—includes co-investigators, Philip Bourne, Christina Bourne and Kenneth Clinkenbeard. Also involved in this contract are staff members Esther Barrow, Patricia Clinkenbeard, Mary Henry and Nancy Wakeham.

Back to the beginning

Barrow, who has family roots in Oklahoma, has been interested in science since his youth.

“I wanted to know what made things tick,” he says.

As a young boy, Barrow wanted to become an M.D. He admired family doctors, some of which actually made house calls. He had a favorite uncle, Dr. Llewellyn Barrow, who graduated from the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine in 1931 and played a major role in the discovery and development of the anti-nausea medication, Dramamine. This uncle, an M.D. in the U.S. Army during World War II, received a citation from a U.S. general for one of the first uses of the drug for the D-Day invasion and the fact that it had saved many lives by preventing sea sickness.

Later Barrow became interested in research. He completed his bachelor’s degree at Midwestern State University, and his master’s degree at the University of Houston focusing on how insecticides affected bacteria in the environment. After earning his master’s degree in microbiology, Barrow became the assistant lab director for the regional health department in Tyler, Texas. It was here that he learned more about bacteriology, mycology, parasitology and serology.

“Every quarter the state tested the lab,” explains Barrow. “We received a group of unmarked samples and we had to correctly identify each bacterial pathogen or parasite, as the case may be. I learned a lot about diseases, what causes them, and how drugs work or don’t work to combat them.”

Barrow returned to graduate school at Colorado State University, where he earned his doctorate in microbiology in 1978 followed by a Heiser Postdoctoral Fellowship at the National Jewish Hospital and Research Center in Denver, Colo. That fellowship was sponsored by the Heiser Fellowship Program for Research in Leprosy. Additional training through an NIH Fogarty Senior International Fellowship was later conducted in the Tuberculosis Unit at the L’Institut Pasteur in Paris, France.

Raising the bar

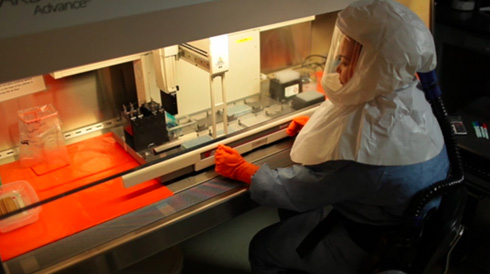

Today Barrow’s research team uses in vitro assay capabilities accomplished with high-throughput screening and electronic database management to test potential drugs —techniques that were established during their first NIAID IDIQ drug screening contract.

“When we received the first NIAID contract, we purchased necessary equipment and developed programs to study the effects of a drug on our inventory of bacteria,” Barrow says. “We can use that same technology to do similar work for this contract.”

Barrow and the team use cultures and some reagents from BEI Resources—the main repository for cultures and reagents for microbiology and infectious diseases research. Their services are also supported by a contract through NIAID.

Barrow credits the good track record his team has and the expertise they have developed by working through the first contract as the reasons the team was awarded this new contract. His wife, Esther, also a microbiologist, has played an important part in the endeavor. Her efforts were instrumental in helping Barrow establish the research program that they brought to OSU, which eventually led to this contract and other NIAID awards.

“Bill is a really nice guy with a good sense of humor and an infectious laugh,” smiles Esther. “Sometimes people don’t see this side of him because he is so serious about his work. He is dedicated and always looking to the next step, the next logical research endeavor and preparing the proposal to compete for funding to make the research a reality.”

They aren’t the only husband/wife duo on the team.

Phillip Bourne’s background is biochemistry. He manages the drugs to be tested as they are received. He also manages the electronic database, develops the robot programs and various drug screening programs and trains individuals on how to run the samples through each system.

His wife, Christina, brings molecular biology and crystallography to the team.

“She focuses on the mechanism of action studies as well as quality control,” Barrow says. “We routinely check our inventory of bacteria to make sure the genotype of the organism remains constant. This allows us to verify to NIAID that the test organisms have not changed and that we tested a particular drug against the strain of bacteria listed in our inventory.”

Ken Clinkenbeard is a co-investigator like the Bournes. He earned his doctorate in biological chemistry and has more than 35 years of experience working with infectious diseases.

“Esther, Patricia (Ken’s wife), Mary and Nancy are the worker bees,” smiles Barrow. “They make sure the tasks get completed and projects keep moving forward. They help train new employees and ensure our high standards of quality work.”

A total of 17 contracts were awarded under this program. Those contracts involve Part A (Bacteria and Fungi), Part B (Viruses), Part C (Parasites and Vectors), Part D (Toxins), and an additional Part E, which provides for a Central Data Management Center that will support the receipt, storage, quality control and analysis of all data generated under Parts A, B, C and D. The contract awarded to OSU’s veterinary center was one of six awarded for Part A.

“We have capabilities that a lot of groups do not have,” smiles Barrow. “You can’t screen certain organisms just anywhere. We have the appropriate laboratories, equipment, protocols and training in place to screen organisms that most institutions aren’t capable of handling. We can use the knowledge and training we have established to work with other groups and bring in more research funding to the veterinary center and to OSU.”

The need for answers

The scope of the work encompasses any type of in vitro assay work needed for infectious disease research, including routine screening of products and development of new in vitro assays and database management of work. According to the NIAID, providing different viable options will allow the NIAID to respond to changing priorities as scientific and public health needs shift, including rapid responses to public health emergencies.

“The importance of this research can best be explained by noting the increasing consequences of emerging infectious diseases and the development of drug resistance in various microbial communities,” Barrow says. “Microbial drug resistance generally develops in human beings as the result of improper use of antimicrobials. As observed in recent years, drug resistance can also develop in animal communities and be transmitted to humans. Look at the case of MRSA infection being transmitted from pigs to humans and the salmonella-related egg recall.”

Antimicrobial drug resistance can develop in all major groups of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), antibiotic resistance has been called one of the world’s most pressing public health problems. On April 7, 2011, the World Health Organization made antimicrobial resistance an organization-wide priority and the focus of World Health Day; they consider drug resistance to be one of the top three threats to human health today.

Since 2001, the NIAID has been establishing a “…comprehensive infrastructure with extensive resources that support all levels of biodefense research.” Having accomplished this solid framework of research and product development over the last several years, the NIAID is “…now transitioning this infrastructure to provide the flexibility required to meet the challenges of emerging, re-emerging and other infectious diseases in addition to biodefense.”

Through the NIAID Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (DMID), a more integrated approach is now being created to perform in vitro assessments of antimicrobial activity for a broad spectrum of pathogens.

According to the NIAID, this strategy is being employed to “…advance science by promoting cross-fertilization across and within disciplines and approaches; serve the research community more conveniently; achieve efficient use of resources through economy of scale and avoidance of duplication; and provide the flexibility needed to respond to changing priorities.”

“This is the reason for the multiple Parts A-E that were established by the new contracts recently awarded,” explains Barrow. “With these new contracts, the DMID is replacing the original in vitro programs with one broad IDIQ solicitation of multiple contracts to provide access to a larger number of qualified contractors, provide increased flexibility for services and thus more effectively cover all areas of current and potential future interests.

“It is the intent of the DMID that the procedures developed through this program will be shared among contractors within the program as well as with the wider research community. This in turn will assist the NIAID in its role in developing medical products to counter various emerging infectious diseases as well as agents of bioterrorism.”

Barrow is confident he and his team’s work will produce tangible results.

“I know that our work has a good chance of leading to the creation of new products to address the issues of emerging infectious diseases and drug resistant strains and that will help make the world a better place for humans and animals alike,” he says.

In addition to benefitting NIAID, Barrow’s team’s research brings tangible benefits to the state of Oklahoma. As a result of the first drug screening contract, the veterinary center was awarded about $8 million. Of that amount, the college received almost $221,000 for renovations, about $500,000 worth of new equipment, about $2 million in indirect costs, and just over $546,000 for a fixed fee. The work generated almost $2.5 million for personnel labor, including fringe benefits. Under the contract, 2.5 percent of the total expenditures were designated to small businesses; some of which are located in Stillwater and other cities in Oklahoma. With the new contract, the OSU Center for Veterinary Health Sciences will be able to continue these research services and maintain its role in the Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Program that is currently evolving at the NIAID and throughout the country.