Apollo 14 member Roosa, a former OSU student, to be honored at 50th anniversary of mission

Tuesday, June 15, 2021

Media Contact: Jordan Bishop | Communications Specialist | 405-744-9782 | jordan.bishop@okstate.edu

Failure was never an option for Stuart Roosa.

Growing up in Claremore, Oklahoma, in the 1930s and ’40s, he knew a strong work ethic and academics would get him where he wanted to be. That red-haired kid’s dedication took him from the Dust Bowl to jumping into forest fires and flying planes and eventually, to the moon.

Roosa, who began his college career at Oklahoma State University, was the command module pilot for the Apollo 14 mission in 1971. His family’s foundation, Back to Space, is hosting the 50th anniversary gala of the event on June 18-19 at Kennedy Space Center.

Although Roosa died of pancreatitis in 1994, his legacy has lived on through his family. All three of his sons joined the military, with Jack Roosa following in his footsteps as a fighter pilot. Jack’s daughter, Danielle Roosa, founded Back to Space in 2017. Its mission is to educate new generations on space travel as well as to honor the pioneers who came before, like her grandfather.

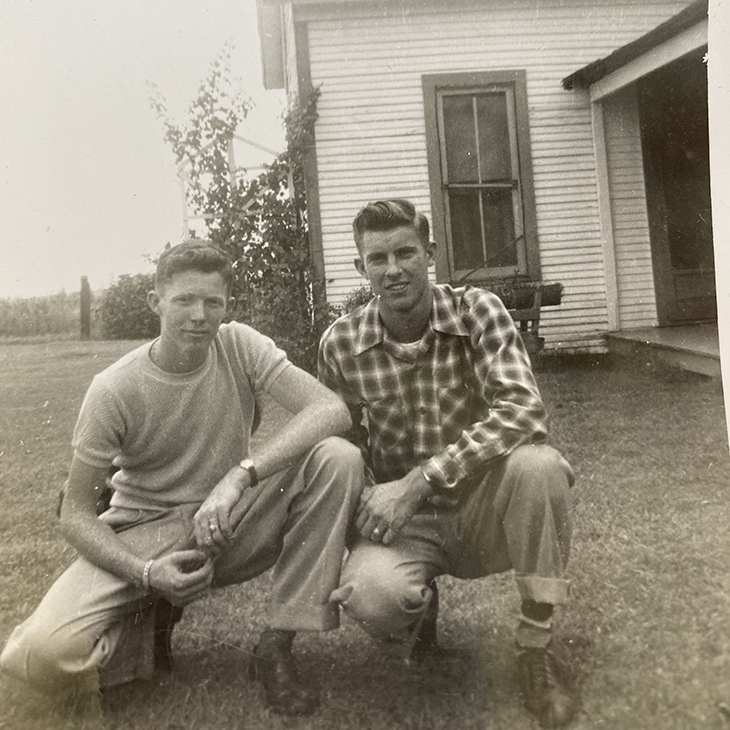

Stuart Roosa studied engineering at then-Oklahoma A&M College in 1951 before transferring to the University of Arizona when his parents moved from Claremore to the Copper State prior to his sophomore year.

In the summer of 1953, after working for the U.S. Forest Service for a couple of semesters, Roosa applied to be a smokejumper. Based primarily in the Pacific Northwest, Roosa jumped into forest fires in remote places where ground crews couldn’t go and spent days at a time stopping the spread of the fires.

“You can't walk right into being a smokejumper; you have to put some time in to get to know who you are,” son Jack Roosa said. “It is highly competitive. It is like being in the Navy SEALs. You are at the top of the pole being a smokejumper. I think that is a testament to my father as to how driven he was. If there was something challenging or being on the top rung of whatever ladder you were climbing, he was extremely driven to go do that.”

After a few years, Stuart Roosa earned a degree in aeronautical engineering from the University of Colorado and joined the Air Force. A fighter pilot, Roosa honed his flying skills before eventually applying to test pilot school, where he graduated in 1964.

After graduating from Edwards Air Force Base in California, most pilots stay on and test advanced aircraft. Roosa again wanted to do something different.

Having heard that NASA was taking another class and on the heels of President John F. Kennedy saying he wanted to put a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s, Roosa applied, knowing it was going to be a long shot.

“He applied, and I want to say it was about six months after submitting his application, he got a call from (Director of Flight Crew Operations) Deke Slayton down at NASA and he said, ‘Why don't you come on down to Houston?’” Jack Roosa said.

Stuart Roosa joined NASA in 1966 as part of the fifth astronaut class. About that time, NASA had begun the Gemini program, based off the success of its Mercury missions. In 1961, Alan Shepard had become the first American to enter space, putting Kennedy’s ambition into play.

When he joined, Roosa knew that he was far down the list of people who would get missions, but he kept at it, waiting to see if he would be chosen. He earned his break when he was put on the support crew for Apollo 9, putting him in the rotation for a spot on the main crew.

On July 20, 1969, the Apollo 11 mission made history, putting the first man on the moon in Neil Armstrong.

The next year, Roosa heard he was going to be named to the Apollo 13 crew, along with Shepard and Edgar Mitchell. However, Shepard hadn’t flown since that famed Mercury mission because of an ear disorder. After surgery in 1968, Shepard was allowed to fly again but NASA figured he needed still more time and bumped Roosa’s crew from Apollo 13 to Apollo 14.

The infamous Apollo 13 flight suffered a blown oxygen tank — with the crew of Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert and Fred Haise acting on the fly to conserve their remaining resources and return home alive.

Because of Apollo 13, Roosa’s crew had to take extra precautions. Pressure was on them as well, with the public wondering if the missions were worth the risk and money. The Apollo 14 crew was flying to prove Apollo 13 was an anomaly and to ensure the Apollo program would continue.

“When Kennedy made the goal for Apollo to land a man on the moon by the end of the decade and they did that, there was a lot of internal discussion within NASA whether they should continue doing this,” Jack Roosa said. “The chances were something bad was going to happen in space, and the worst thing that could happen was killing some folks in space.”

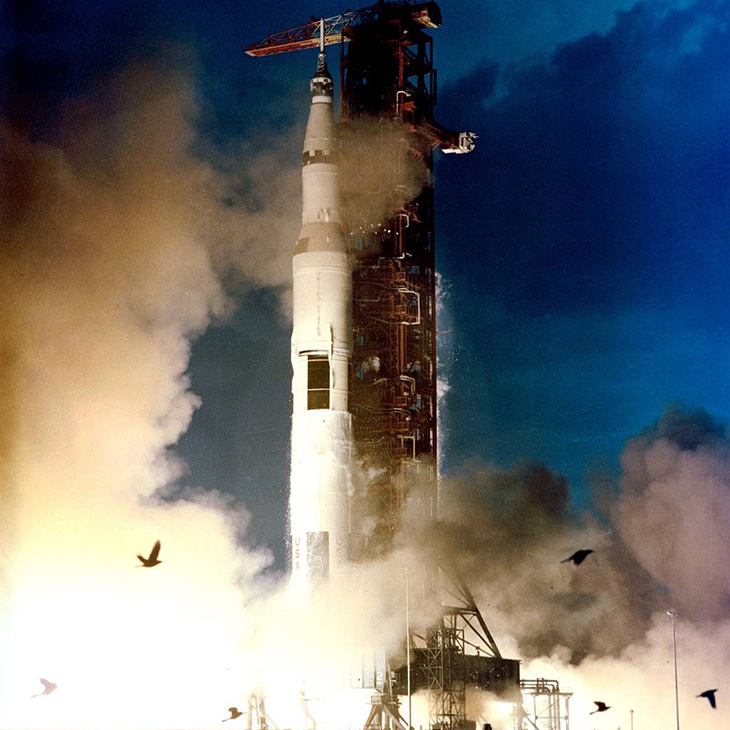

The rocket launched on Jan. 31, 1971. Their mission was to collect geological data near the same place where the Apollo 13 crew was supposed to land.

Out of the gate, Apollo 14 had problems, first with a 40-minute weather delay at launch and then during the docking procedure in space which could have ended the mission.

Eventually they did dock, and the mission continued. The lunar landing crew of Shepard and Mitchell set foot on the moon on Feb. 5.

Meanwhile, Roosa orbited the moon in the command module Kitty Hawk for two days. There, he took photos of the moon’s surface and scouted out future landing sites. After hooking back up with Mitchell and Shepard, the crew returned to Earth on Feb. 9.

Roosa also carried out a special mission for the Forest Service, bringing hundreds of tree seeds into orbit with him, which were later planted as “moon trees” after his return.

Jack, who was 10 at the time, said it was an odd time for the family with the media hoopla around the house. It was a whirlwind, from all the press coverage to the events after the mission that included a ticker tape parade in Chicago and a visit to the White House to have a state dinner with President Richard Nixon.

“So you got to go through some very unique and once-in-a-lifetime events,” Jack Roosa said. “You go through all of that and then the spotlight moves to another family and then you go back to school. As you get older in life, you reflect on how phenomenal it all was.”

As quickly as it began, the coverage moved on to the next flight. Stuart Roosa, who would have been in rotation to be a commander and land on the moon in a later Apollo mission, never got the chance as the program was canceled in 1972. Budget cuts following Apollo 17 were to blame.

Roosa left NASA to go into the private sector in 1976, retiring as a colonel from the Air Force. One of only 24 men to travel to the moon, Roosa spent 217 hours in space.

“I think for the astronauts, it is a tough transition,” Jack Roosa said. “You are at the career top of your Air Force/astronaut field, and you are fairly young. My dad was 37 when he flew. The old saying is you don't want to peak early and for those folks who are in their mid- to late 30s and they think, ‘I just accomplished something historic;’ sometimes it is hard to get excited about the next gig, whatever it may be.”

Stuart Roosa later became the owner and president of Gulf Coast Coors in Mississippi. Roosa Elementary in Claremore is named for him.

Growing up watching his dad’s accomplishments, Jack wanted to be just like him, eventually joining the Air Force and becoming a fighter pilot, flying in 80 combat missions during his 20 years of service.

“My dad and I had a passion for flying so when we would get together during my Air Force career, we would sit together and tell flying stories,” Jack Roosa said.

Jack has retired from the Air Force but he helps out with Back to Space and enjoys getting to teach kids about what his father did and also connecting with astronauts who worked with his dad.

He is happy to see the interest in space is coming back and thinks Danielle launched Back to Space at just the right time.

“Danielle started this because that was not there. Because space wasn’t cool and wasn’t in pop culture anymore. She always said this joke that she asked someone who was her age, ‘Who went to the moon?’ and they would say ‘Lance Armstrong,’” said Heather Sisson, chief marketing officer for Back to Space. “She said there was a huge gap there and wanted to make space cool and approachable and really talk about the legacies, too. That was the spark for Danielle.”

A for-profit program, Back to Space works with students in STEM disciplines and has learning programs and hands-on activities to help educate. A television program and a lunar landscape facility in the Dallas-Fort Worth area are also in the works.

While the Apollo 14 crew is honored at the gala, the Roosa family is proud to have been a part in ensuring the mission has not been forgotten and hopes that someday, travel to the moon and beyond will happen again.

To find out more about the Back to Space foundation, go to backtospace.com. Proceeds from the 50th Anniversary Gala will go to the Gary Sinise Foundation and the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation.