Kara Lab develops new method to improve spacecraft landing safety

Tuesday, December 9, 2025

Media Contact: Desa James | Communications Coordinator | 405-744-2669 | desa.james@okstate.edu

Space missions hinge on stability, and researchers from the College of Engineering, Architecture and Technology at Oklahoma State University are reshaping how engineers predict it.

Dr. Kursat Kara, associate professor in the School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, and Ph.D. candidates Shafi Al Salman Romeo and Ashraf Kassem have developed a method to accurately predict the behavior of a space capsule during atmospheric entry. This advance supports safe landings on Earth and other worlds with atmospheres.

The research introduces a Data-Fusion-based Nonlinear Parameter Identification framework, combining experimental data with advanced simulations to better characterize the dynamic stability of blunt-body vehicles, the capsule shape used for many NASA missions. By treating experiments and simulations as complementary evidence within a unified probabilistic model, DF-NPI provides an uncertainty-aware, data-driven path to identifying nonlinear stability behavior.

Dynamic stability refers to how a capsule responds to disturbances and unsteady aerodynamic moments during entry and descent.

“When a space capsule reenters an atmosphere, the flow around it becomes highly unsteady,” Kara said. “If it is dynamically stable, the wobbles naturally fade away, and the capsule ‘self-corrects,’ keeping its heat shield facing into the flow.”

If the capsule is unstable, it can:

• Expose parts of the vehicle that were never intended to face the highest temperatures.

• Increase structural loads and the G-forces experienced by the crew or instruments.

• Make its flight path less predictable, pushing it away from the planned landing

zone.

Dynamic stability is essential for a safe landing, as it helps protect the capsule, manage structural loads, maintain targeting accuracy and enable reliable parachute deployment.

Dr. Kursat Kara

Associate Professor of Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering

Closing gaps in spacecraft analysis

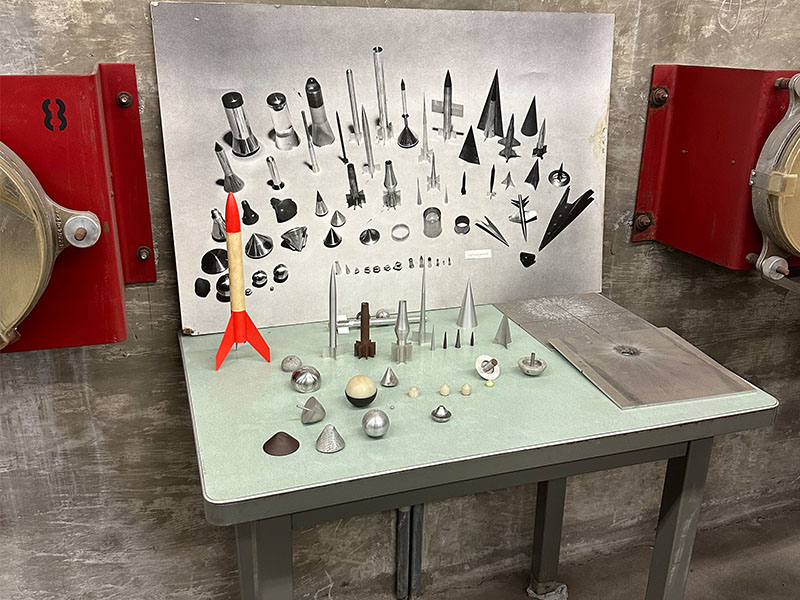

Engineers rely on three primary approaches to study capsule stability, but each has limitations.

Wind tunnel testing often requires mounting a model on a support system that can disrupt the flow. Ballistic-range tests offer greater realism but typically provide limited time histories — like watching only every tenth frame of a movie. High-fidelity computational simulations provide dense detail but can introduce modeling bias.

Because a capsule can experience large angles of attack and complex motion during real entry, stability models based on a single approach may not fully capture its nonlinear behavior over the whole trajectory.

“We developed DF-NPI because we needed a way to combine these different, imperfect sources into a single, consistent picture,” Kara said.

The framework integrates ballistic test data and free-flight computational fluid dynamics using Bayesian inference and Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling. It reconstructs flight trajectories by fusing experimental and simulated data and estimates how stability changes with angle of attack.

In simple terms, DF-NPI asks: What stability characteristics would make both the simulations and the experiments agree — and how certain are we about that answer?

Kassem points out that combining real experimental data with advanced computer simulations provides a significant advancement in assessing the dynamic stability of vehicles during atmospheric entry.

“By using a Bayesian formulation that explicitly captures uncertainty, it provides a clearer picture of a vehicle’s motion as it descends,” Kassem said. “This advancement supports the design of safer spacecraft and more dependable mission planning.”

Romeo notes that this research is tackling a well-known problem and considers the experience rewarding, especially knowing the work may make landing safer for future space missions.

“Entry vehicles behave in complex ways, and no single test tells the full story, so we needed a tool that could capture that complexity,” Romeo said. “Developing a method that blends experimental and simulation data allows us to reduce uncertainty and improve how we predict stability during descent.”

Better design, fewer tests and safer landings

Kara points out that this research can assist future planetary entry missions in three key ways.

“It provides more accurate predictions of wobbling, indicates where uncertainties exist, and reduces the amount of costly physical testing required,” Kara said.

By reducing reliance on large numbers of physical tests, DF-NPI can help build a high-fidelity aerodynamic database from a smaller, strategically designed set of experiments, lowering costs and accelerating design decisions.

The research team collaborated with NASA Ames Research Center engineers who contributed expertise in free-flight computational fluid dynamics and trajectory reconstruction.

“Their input helped us select realistic test cases, interpret the results physically, and refine the DF-NPI outputs, which NASA engineers can ultimately utilize,” Kara said.

The research team would also like to express their appreciation to co-PI, Dr. Omer San from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, for his exceptional collaboration. Additionally, special thanks are given to Cole Kazemba, Dirk Ekelschot and Jeffrey Hill from NASA Ames Research Center, whose expert feedback significantly advanced the project.

These CEAT researchers have answered the call by advancing discovery with tools that could make future atmospheric-entry missions safer, more efficient and more predictable.

This research is part of the Kara Lab's NASA Early Stage Innovations (ESI) project: Physics-Guided Multifidelity Learning for Characterization of Blunt-Body Dynamic Stability (Grant No. 80NSSC23K0231).