Younger T.rex bites were less ferocious than their adult counterparts

Friday, March 12, 2021

By closely examining the jaw mechanics of juvenile and adult tyrannosaurids, some of the fiercest dinosaurs to inhabit earth, scientists from the University of Bristol and OSU College of Osteopathic Medicine at the Cherokee Nation have uncovered differences in how they bit into their prey.

Geology Ph.D. student Andre Rowe from the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom along with Eric Snively, Ph.D., and associate professor of Anatomy at OSUCOM at the Cherokee Nation authored the research on T. rex’s bite as it grew up. They applied engineering methods to the lower jaws of baby, teenage and adult tyrannosaurs to find out how much stress and where stresses from the bite were channeled through the mandibles.

The researchers found that younger tyrannosaurs were incapable of delivering the bone-crunching bite that is often synonymous with the T. rex and that adult specimens were far better equipped for tearing out chunks of flesh and bone with their massive, deeply set jaws.

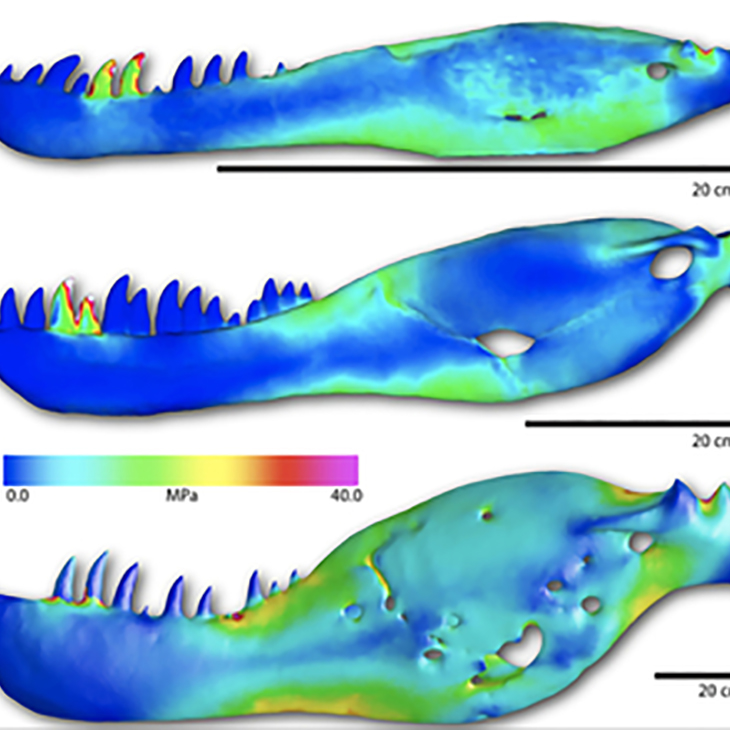

Snively said they applied virtual muscle forces to 3D computer models of the tyrannosaur jaws with a method called finite element analysis.

“The method is useful for orthopedic and sports medicine research, and we turned its spotlight on the dramatic phenomenon of T. rex feeding,” he said.

They also were able to use previous T. rex research conducted by OSU Center for Health Sciences Associate Professor of Anatomy Paul Gignac, Ph.D. Adult tyrannosaurids have been extensively studied due to the availability of relatively complete specimens that have been CT scanned.

The availability of this material has allowed for studies of their feeding mechanics. The adult T. rex was capable of a 60,000 Newton bite (for comparison, an adult lion averages 1,300 Newtons), and there is evidence of it having actively preyed on large, herbivorous dinosaurs.

The team were interested in inferring more about the feeding mechanics and implications for juvenile tyrannosaurs.

The main hypothesis was that larger tyrannosaurid mandibles experienced lower peak stress, because the jaws became deeper and wider relative to length as they grew, and that younger tyrannosaurids experienced greater stress and strain relative to the adults, suggesting relatively lower bite forces consistent with proportionally slender jaws.

But their research found the juveniles experienced lower absolute stresses when compared to the adult, meaning adult tyrannosaurs would experience high absolute stresses during feeding but shrug it off due to its immense size.

“As T. rex grew, its jaw muscle forces seem to have increased even faster than the strength of its mandible. The jaws of adults were so deep that they still absorbed the high forces without much trouble,” Snively said.

"Like a honey badger, adult T. rex just didn't care."

However, when mandible lengths are equalized, the juvenile specimens experienced greater stresses, due to the relatively lower bite forces typical in slender jaws,” said lead author Rowe.

“Tyrannosaurids were active predators and their prey likely varied based on their developmental stage. Based on biomechanical data, we presume that they pursued smaller prey and fulfilled an environmental role similar to the ‘raptor’ dinosaurs such as the dromaeosaurs,” he said. “Adult tyrannosaurs were likely subduing large dinosaurs such as the duckbilled hadrosaurs and Triceratops, which would be quickly killed by their bone-crunching bite.”

Rowe said that he hopes future researchers continue to delve into CR and surface scanning of dinosaur cranial material and more application of 3D models in dinosaur biomechanics research.

“This study illustrates the importance of 3D modeling and computational studies in vertebrate paleontology — the methodology we used in our study can be applied to many different groups of extinct animals so that we can better understand how they adapted to their respective environments,” he said.

To the public, T. rex is paleontology’s mightiest prima donna, Snively said, but researchers don’t always see tyrannosaurs that way.

“At OSU, we’re also interested in T. rex as another animal in its ecosystem and how it interacted with its environment throughout its life,” he said. “The juveniles were hunting and eating in different ways than the adults and were just as important.”

MEDIA CONTACT: Sara Plummer | Communications Coordinator | 918-561-1282 | sara.plummer@okstate.edu