Research into tyrannosaur feet may one day help treat sports injuries

Monday, December 19, 2022

Media Contact: Sara Plummer | Communications Coordinator | 918-561-1282 | sara.plummer@okstate.edu

There’s no debate that Tyrannosaurus rex’s monstrous teeth and jaws — and its multi-ton bite force — were instrumental in the dinosaur’s ability to catch and eat prey. But what about their feet?

A group of health professionals, scientists and paleontologists, including two anatomy professors from Oklahoma State University College of Osteopathic Medicine, recently published a study into tyrannosaurs’ unique feet and how they may have played a role in this dinosaur family’s success as top predators — and how their findings could help treat or prevent sports injuries in humans.

Tyrannosaurs have longer feet for their body size than other carnivorous dinosaurs. The large middle bone of the foot is triangular when viewed from the front or in a cross section and then it tapers to become narrow at the ankle.

In previous studies by Eric Snively, OSU-COM associate professor of anatomy, and Thomas Holtz, vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Maryland’s Department of Geology, they found this unique long bone called arctometatarsus enabled tyrannosaurs to have relatively fast forward motion.

“People have long been attracted to the awesome power and ridiculously small arms of Tyrannosaurus rex and its kin, but the legs and especially the feet of the tyrant dinosaurs were also highly specialized,” Holtz said. “This new study helps to show that even on a microscopic level, tyrannosaurs were adapted for both long-distance running and rapid acceleration.”

The new research looks at whether large ligaments in tyrannosaurs potentially strengthened the sole of the foot near the toes — a unique feature among large dinosaurs and a pattern not found in any modern animal.

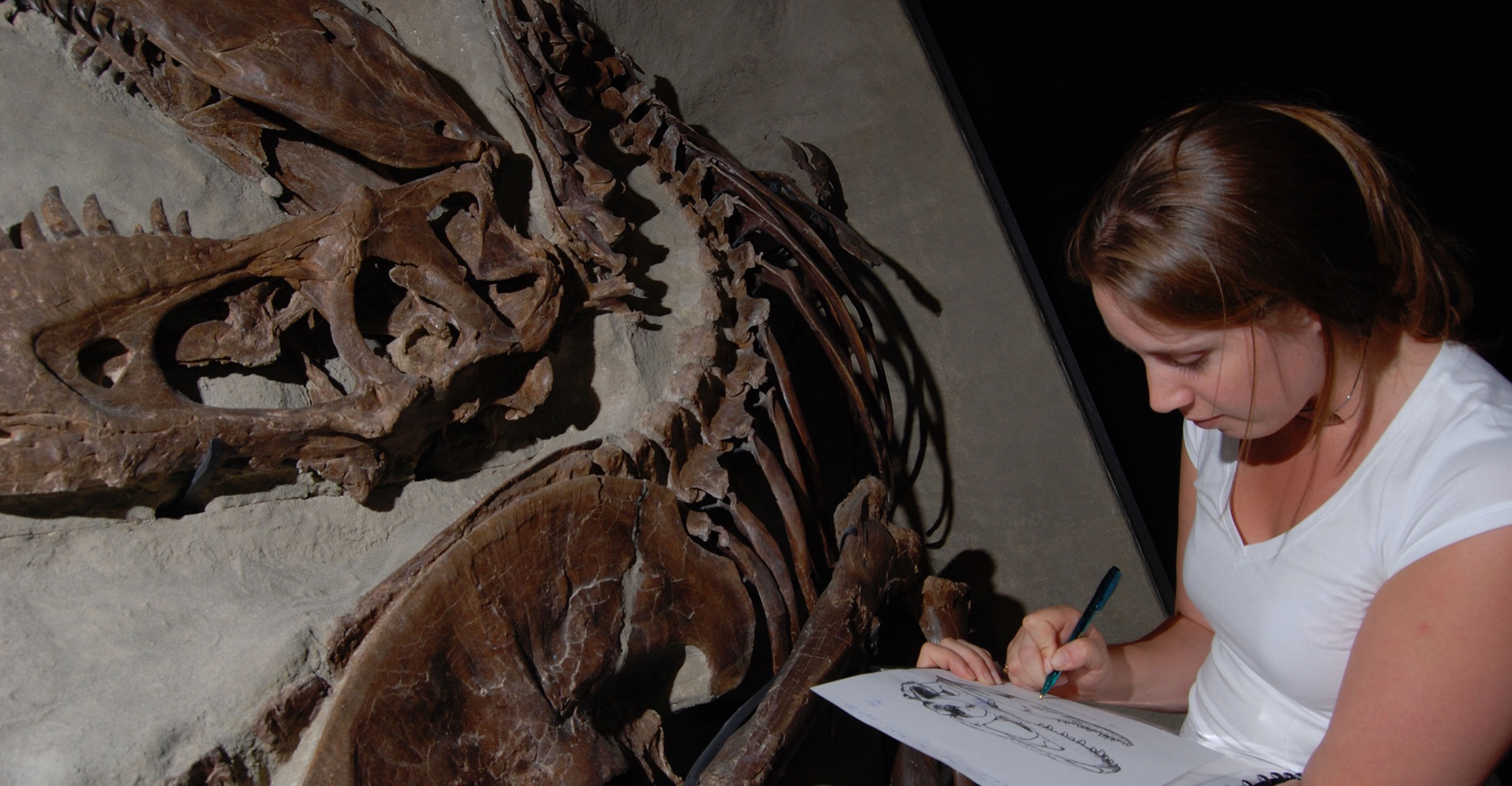

Large ligaments leave behind rough surfaces on bone, which Snively identified in tyrannosaur fossils. Then, University of Calgary Emeritus Professor of Biological Sciences, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Anthony Russell showed how the pull of ligaments and tendons forces bone into rough, undulating surfaces.

But since soft tissue like ligaments aren’t fossilized, it was difficult to test the hypothesis until the study’s lead author Lara Surring, primary care paramedic with Alberta Health Services, realized they could test for ligaments by training a scanning electron microscope on the rough surfaces of the tyrannosaur fossils and compare to other carnivorous dinosaurs.

For this study, Surring said the team was not only curious to see how some of the largest land animals to ever exist were able to maintain function and strength in their lower limbs at such large sizes, but how their findings could help in modern medicine.

Ligament and tendon injuries are common in humans and make up around 30-50% of sports injuries. How these structures attach to bone influence the likelihood for joint or avulsion injuries when over exertion pulls tendons and ligaments from their attachments to bone.

“Exploring fossils reveals clues as to how the skeletal system has adapted in various ways through time,” she said. “We are hopeful that learning how tyrannosaurs made skeletal adjustments to stay functional at the limits of animal size will eventually help us to evaluate and improve human skeletons after injury or aging. This research is one more step in that direction.”

Surprisingly, tyrannosaur feet have direct and unexpected parallels with human performance as humans and tyrannosaurs both seem to have adapted to long-distance walking and running.

Daniel Barta, assistant professor of anatomy at OSU-COM at the Cherokee Nation, and Michael Burns, associate professor of biology at Jacksonville State University extracted thin sections of metatarsal bones from a tyrannosaur and a control dinosaur, a small carnivore Coelophysis.

The scanning electron microscope revealed pits in the rough bone surface, exactly matching tight ligament attachments in modern animals. The internal bone structure of the tyrannosaur showed mineralized ligaments that anchored the sinews within the bone, while the control carnivore dinosaur lacked such strong attachments.

“With external and internal microscopy revealing its faded soft tissue, one small step for a tyrannosaur advances our understanding of a vivid past,” Snively said.

Surring discovered even more ligament attachments that bound the foot together both externally and internally, and this new scanning electron microscope method enabled the researchers to rigorously test for the presence of soft tissue in fossilized animals.

“Although we’ve known about fossils for millennia, and dinosaurs for centuries, fossils can continuously provide new information as we can apply newer and more sophisticated analytical techniques,” Burns said. “Hard-tissue histology and electron microscopy shed new light on old bones in this study. Future students and researchers will undoubtedly develop new techniques to answer the questions we can’t currently solve.”