Prehistoric whales evolved large brains earlier than once thought while retaining sense of smell

Friday, July 25, 2025

Media Contact: Sara Plummer | Senior Communications Coordinator | 918-561-1282 | sara.plummer@okstate.edu

In the desert just west of Faiyum, Egypt, is the world’s largest concentration of prehistoric whale fossils, a UNESCO World Heritage site called Wadi Al-Hitan — Whale Valley.

Abdullah Gohar, a Ph.D. student in anatomy and vertebrate paleontology at OSU Center for Health Sciences, grew up in Faiyum and now studies how whales evolved from prehistoric land mammals to living fully in water.

“It has hundreds of complete whale skeletons all over the place,” Gohar said. “The earliest whale fossils came from the Eocene epoch, which is basically from around 55 million years ago until 33 million years ago. This is the golden age of whales because they started there and continue today.”

At OSU-CHS, Gohar studies under paleontologist Holly Woodward Ballard, PhD., a professor of anatomy specializing in paleohistology.

He is also one of several co-authors from universities in Germany, Italy, Egypt and Oklahoma whose research into the evolution of whale brains was recently published in the scientific journal Evolution.

The researchers studied high-resolution CT scans of the skull fossils of two early whales: Protocetus, which lived about 43 million years ago, and Aegyptocetus, which lived about 41 million years ago.

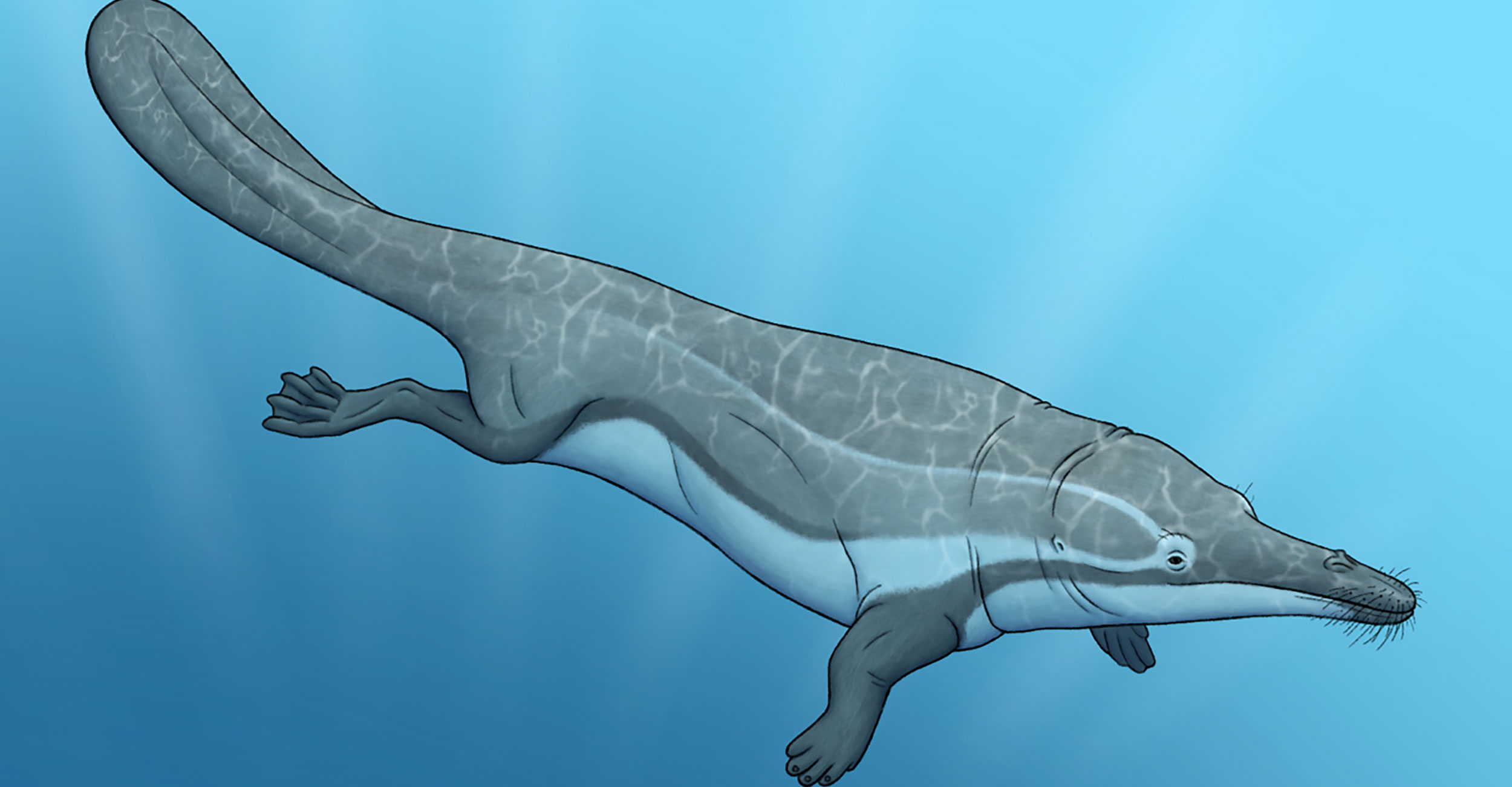

Both were semi-aquatic whales, meaning they spent time on land as well as in water, based on the olfactory bulbs and canals and other elements of their anatomy and morphology.

Gohar said they had a complex ethmoid bone, which separates the nasal cavity from the brain.

“If you have well-developed ethmoid bones, this means you have a complex sense of smell,” he said. “The living whales today have either a really reduced sense of smell, like in baleen whales or a completely absent sense of smell, like in dolphins or toothed whales. But terrestrial mammals, because they need this on land, they have a well-developed sense of smell.”

This further supports the evidence that Aegyptocetus and Protocetus were midpoint species in the evolution of whales from terrestrial to fully aquatic mammals, Gohar said.

Using the CT scans of the interior of the skull fossils, the team was also able to study the brain cases to determine the brain size relative to the overall size of both animals.

“Cetaceans today — whales, dolphins, porpoises — have one of the largest brains relative to their body size. I think they come second after primates. Scientists always believed that this happened after they became fully aquatic. The adaptation to be fully aquatic triggered them to have a very large brain size relative to their body size,” he said.

But studying the brain cases of Protocetus and Aegyptocetus, Gohar said the research team found that wasn’t the case with these semi-aquatic whales, which were roughly 10 to 13 feet long.

“They are not fully aquatic yet, but they still have this large brain size relative to their body size,” he said. “This means that Protocetus not only has a big brain size relative to its body size but also has a well-developed sense of smell. This sense of smell isn’t important when they are diving underwater, but it’s actually very important on land.”

Gohar said early whales remained in this semi-aquatic state for a long time, about seven to 10 million years, before becoming fully aquatic.

“It was really important for them to cool down because the Eocene epoch, the time of the origin of whales, it was a really, really hot time. They experienced significant global warming at that time,” he said. “This is one of the hypotheses of why they went into the water in the first place, to cool down and search for food, because there were not a lot of animals living on land at that time because of the hot weather.”

Woodward Ballard said that knowing that these semi-aquatic whales had large brain sizes and a well-developed sense of smell simultaneously millions of years ago can help us understand animals today.

“The paper’s authors show that brain enlargement began while whales still relied on terrestrial environments, suggesting it was a pre-adaptive trait that supported their shift to a fully aquatic ecology,” she said. “Understanding this sequence of trait acquisitions also helps predict how modern amphibious mammals like seals and otters might evolve.”

Gohar is also part of a research team led by Egyptian paleontologist Hesham Sallam, a professor at the American University in Cairo and founder of the Mansoura University Vertebrate Paleontology Center in Mansoura, Egypt.

Sallam, who is also a co-author on the study, said it’s an exciting time to be a paleontologist studying these fossils found in Egypt.

“Egyptian fossils remain a goldmine for understanding major evolutionary transitions, such as the evolution of whales. Studying the brain anatomy of these ancient whales offers us a unique window into the moment when whales began to cognitively diverge from life on land while still retaining their ancestral sensory ties to it,” he said.

Gohar said he will continue to study the evolution of whales before he graduates from OSU-CHS in a few years. Then, he plans to return to Egypt to continue his research and pass on what he has learned to others.

“The first thing I want to do is transfer the knowledge. The Ph.D. students from Dr. Sallam’s lab, like me, who now live in the United States or elsewhere, are giving virtual lectures to the next generation of undergrads or even primary school or secondary school students who are passionate about fossils or dinosaurs,” he said. “After I finish my Ph.D., I want to go back to Egypt and transfer all the scientific knowledge I have about whale evolution to the next generation.”