The truth of Oklahoma’s state fossil revealed

Monday, March 17, 2025

Media Contact: Sara Plummer | Communications Coordinator | 918-561-1282 | sara.plummer@okstate.edu

One of Andy Danison’s favorite dinosaurs growing up was the carnivore Saurophaganax. Originally found in the Morrison Formation in the Oklahoma panhandle in the early 1930s, the bones attributed to Saurophaganax later became Oklahoma’s official state fossil.

But Saurophaganax, which translates to lord of the lizard eaters, has always been a drama king.

After their discovery, the fossils were named Saurophagus maximus, which was later considered invalid. In 1995, the material was reassessed and given the valid name Saurophaganax maximus. However, since its discovery, researchers have doubted whether this dinosaur is actually distinct from the better-known Allosaurus.

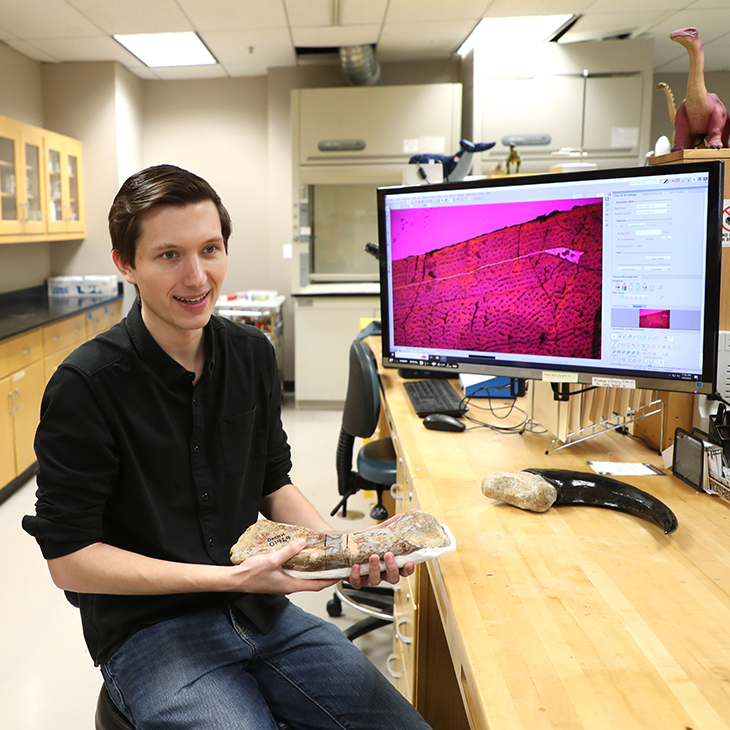

Now, Danison, an anatomy and vertebrate paleontology Ph.D. student at OSU Center for Health Sciences, has reanalyzed the fossils and found that one of his favorite dinosaurs doesn’t exist as originally described.

“When I became a paleontologist, I said there are things I want to accomplish in this career, and the first on that list was to figure out what was going on with Saurophaganax,” he said. “There’s been a long-standing controversy about whether it was just a really big and skeletally mature Allosaurus, or whether it was justifiably its own genus.”

Through painstaking analysis of claw, metatarsal, tail and vertebra bones and comparing them to similar fossils of other known species, Danison determined that some of the fossils attributed to the carnivorous theropod more likely belonged to herbivorous sauropods from the same site.

“All the bones were jumbled together from the same site; we were able to pick through those and make some really nice comparisons. We showed that a lot of these bones were not from the carnivorous dinosaur we thought they were,” he said, but instead are bones from at least three species of dinosaur — a carnivore and two herbivores.

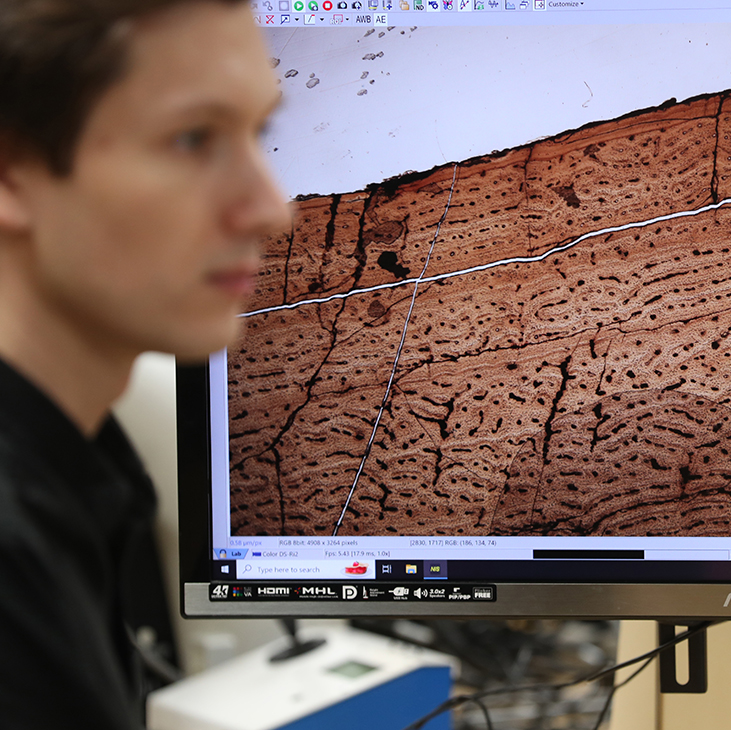

A paleohistological analysis of a metatarsal that examined the tissue inside the bone pointed to a new species that Danison named Allosaurus anax, which translates to "different lizard lord."

Studying a cross-section of the carnivore’s bone determined that it had reached skeletal maturity at a much larger size, supporting the hypothesis that it is distinct from other species of Allosaurus.

Danison said Allosaurus anax would have been around 40 feet long and could weigh up to five tons — about the average weight of an African elephant — making it the largest species of Allosaurus.

“This would make it the same length of a T. rex, but notably lighter,” he said, since T. rex could weigh up to seven tons or more.

Danison said additional research and comparisons of known herbivore fossils will need to be made to determine the species of the unknown herbivore bones once thought part of Saurophaganax.

After almost two years of research and analysis, Danison and his fellow researchers published their findings in the December 2024 issue of the peer-reviewed scientific journal Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Paleontology, which received considerable attention.

“I think within the first 10 days of coming out, more than 2,800 people had actually downloaded the paper, and a bunch of artwork was made online inspired by it, so I was really happy,” he said.

It was in Holly Woodward Ballard’s paleohistology class that Danison first brought up the question of Saurophaganax’s legitimacy — something Ballard, a Ph.D. and professor of anatomy at OSU-CHS, had wondered about herself.

“I was pleased to see a student thinking in a similar way and suggested he explore that question using histology and morphology. I am so impressed by the initiative and tenacity of Andy to put this project together and see it to completion so quickly,” said Ballard, who is also a co-author of the paper. “At the same time, Andy’s attention to detail and care to ensure his methods were rigorous speaks to a level of integrity that I would expect in a more seasoned researcher.”

Eric Snively, Ph.D., and associate professor of anatomy at OSU College of Osteopathic Medicine at the Cherokee Nation, is also a co-author and Danison’s advisor.

“It’s fun to see a researcher’s confidence build while maintaining the healthy self-skepticism that drives good science,” Snively said. “We kept reminding him that he’s the world’s expert on the bones, and he’s been more rigorous about studying them than anyone else. I think around the time of publication, he started to believe it.”

“I think within the first 10 days of coming out, more than 2,800 people had actually

downloaded the paper, and a bunch of artwork was made online inspired by it, so I

was really happy.”

Regarding Saurophaganax no longer being a recognized species, Danison admits he’s a little sad about it. However, he knew that was a possible outcome when he decided to research this controversial dinosaur.

“I went back and forth, and I originally thought it was going to be its own genus, but when I realized that probably wasn’t going to be the case, I was sad but very excited that I had accomplished what I had set out to,” he said. “I was really OK with either outcome. I would have loved it either way. I was just happy to be working on the material.”

And while this research determined that Oklahoma’s state fossil actually came from three different dinosaurs, the impact of Danison’s study goes beyond the state’s borders, said Daniel Barta, Ph.D., assistant professor of anatomy at OSU-COM at the Cherokee Nation and one of the paper’s co-authors.

“More broadly, I hope this finding brings further attention to museums and their collections as powerful engines of scientific discovery and education. Fossils like Saurophaganax that were first discovered many decades ago are still revealing their secrets, including new species,” Barta said. “It’s vital that we continue to preserve and study the paleontological heritage of Oklahoma and share our findings in a way that inspires people of all ages to learn more about nature and consider a career in science.”