On the Job with a CVHS Veterinary Cardiologist

Friday, February 13, 2015

Like humans, cats and dogs can develop heart disease. Some breeds are more likely than others to develop heart problems.

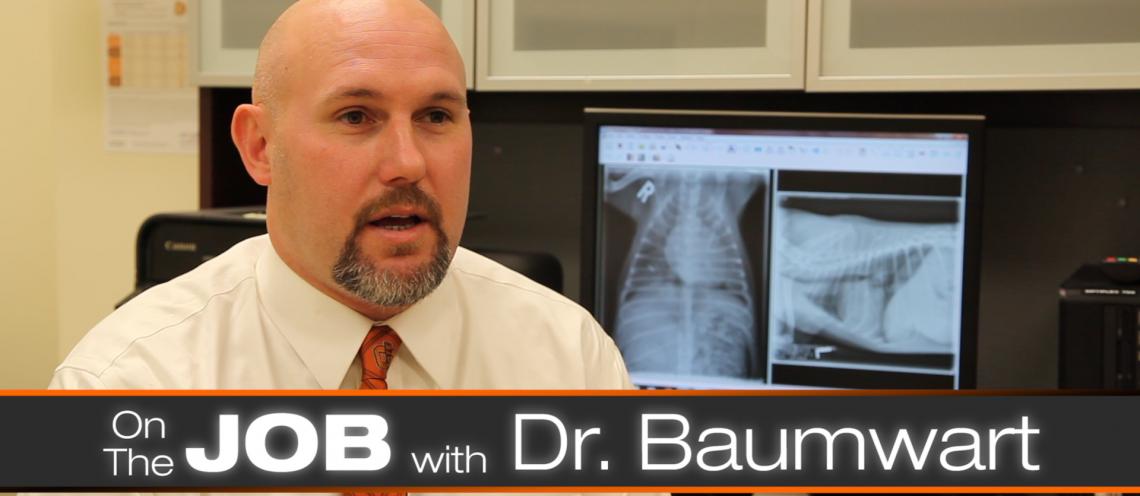

The Veterinary Medical Hospital at Oklahoma State University’s Center for Veterinary Health Sciences has a board-certified veterinary cardiologist on staff — Dr. Ryan Baumwart — to help owners treat heart disease in their pets. According to Baumwart, the hospital sees approximately four to five primary cardiology cases daily.

“When people ask me what I do for a living, they are sometimes surprised to learn I am a veterinary cardiologist,” Baumwart said. “Many don’t even know that there is such a thing. A typical referral to the hospital’s cardiology section entails a review of the patient’s history — what tests have been done on the animal, what has been discovered, the medications prescribed to the pet, and what has worked or hasn’t worked, which can be very helpful. Then, I’ll examine the patient. Usually, we will do a cardiac ultrasound of the heart (echocardiogram) to help figure out what is happening with the heart.”

Like human medicine, a cardiology exam at the veterinarian can involve chest radiographs or X-rays and electrocardiograms (EKG or ECG).

“Sometimes there are electrical problems of the heart. We’ll attach the patient to EKGs to help determine what those problems are,” Baumwart said. “The majority of the time, an ultrasound will tell us what is going on structurally with the heart. Then, we try to tailor a therapy to make the animal feel better.

“In some instances, unfortunately, there is nothing that can be done for the pet if we are dealing with things like cancer. Usually, a medical option or a surgical option can help improve the patient’s overall health.”

Baumwart explains that most dogs will develop heart disease at some point. In some cases, it comes sooner rather than later and needs to be addressed to maintain the pet’s quality of life.

“Doberman pinchers are one of the breeds pre-disposed to heart disease. More than 50% of Dobermans get a dilated cardiomyopathy of their heart where their muscle fails. It’s a genetic problem,” Baumwart said.

“Cavaliers are the poster child for having a valve problem with 100% of that breed affected. It’s just a matter of when they get it. We see some Cavaliers that get it at 2 or 3 years of age. Most of the time in other breeds of dogs if we are going to see problems, we don’t see it until 10 or 12 years of age.

“All dogs get some degree of heart disease. As the dog ages, the valves thicken, which can lead to some leakage of the heart valves. Fortunately, they all don’t have problems because of this. It’s kind of like arthritis in older pets.

Baumwart comes from a long line of OSU veterinarians.

“I grew up in a family of veterinarians. My father is a veterinarian in western Oklahoma, and my brother and sister have followed in his footsteps. I grew up around it and loved it. I couldn’t think of anything better to do than veterinary medicine,” Baumwart said.

“I chose veterinary cardiology because, early in my vet school career, the heart was difficult. It wasn’t the easiest thing to understand. I think that’s what kind of drew me to it. Then, I did an off-campus rotation in Los Angeles, where I could be around cardiology. It was a high-paced practice. We saw a lot of cases, including some famous people’s dogs, which made it even more fun. Then, during my internship, I was around some excellent cardiologists who further solidified my desire to go into cardiology.”

Baumwart earned his DVM degree from OSU in 2002 and completed a rotating internship there.

“I was fortunate enough to stay in Ohio for my residency in cardiology. It was a four-year program that I completed, and I then passed my board certification in cardiology,” Baumwart said.

Baumwart is one of 28 board-certified specialists on staff at Oklahoma State Veterinary Medical Hospital. These veterinarians are experts in their fields, ranging from cardiology to ophthalmology to surgery to internal medicine. At OSU, Baumwart has not only access to his colleagues' expertise but also to specialized equipment.

“While many veterinarians have an ultrasound in their practice, it does take a specialized ultrasound to do hearts well,” Baumwart said. “One ultrasound is not equal to another. The more you pay, the better the image often. We have a high-quality ultrasound and can do in-hospital ECGs or electrocardiograms. At the hospital, we also have the technology to monitor and read the patient for 24 or even 48 hours. Then, using a particular computer program, we can look at the information and analyze it to better understand what is happening in the patient’s heart.

“I enjoy being back here at the University and seeing various animals. I recently came out of private practice, where we saw a lot of cats and dogs. They get a lot of heart disease. Here, we treat not only dogs and cats — which I love — but we see the occasional iguana, horse, or cow.

“The thing I enjoy the most about cardiology is the surgical side of things and doing some of the interventional surgery procedures,” Baumwart said. “For example, putting a pacemaker in a dog that is passing out. The dog goes from passing out ten times a day to not passing out at all. It’s very rewarding.”

Baumwart will rely on specialized X-rays, which are basically recording devices, during some of those surgeries.

“It’s an X-ray that gives us real-time images instead of static images. This technology allows me to place wires and catheters into the heart and see where they are going,” Baumwart said. “We recently had two challenging cases where I thought I was in one side of the heart, and I ended up being on the other side of the heart — not that it hurt the dog. It was just one of my more challenging moments. I may not deal with these big pieces of equipment daily, but it’s beneficial in treating our cardiac patients.”