OCD in Dogs is a Growing Problem

Monday, April 20, 2015

At just 9 months old, Tripp Traw weighs over 80 pounds. He is a Great Pyrenees mix owned by JoAnn Traw of Farmington, Ark. The puppy underwent surgery at Oklahoma State’s Veterinary Medical Hospital for a common problem in young, growing large breed dogs—OCD.

“Osteochondritis Dissecans, or OCD, is a disease of developing bone and cartilage,” Dr. Mark Rochat, small animal surgery section chief, explained. “Bones start as cartilage and change into bone over the first few months of life. Sometimes in the joint, the cartilage doesn’t change into bone and instead thickens. Then the thickened spot becomes a flap and causes pain.”

Tripp’s veterinarian diagnosed the problem.

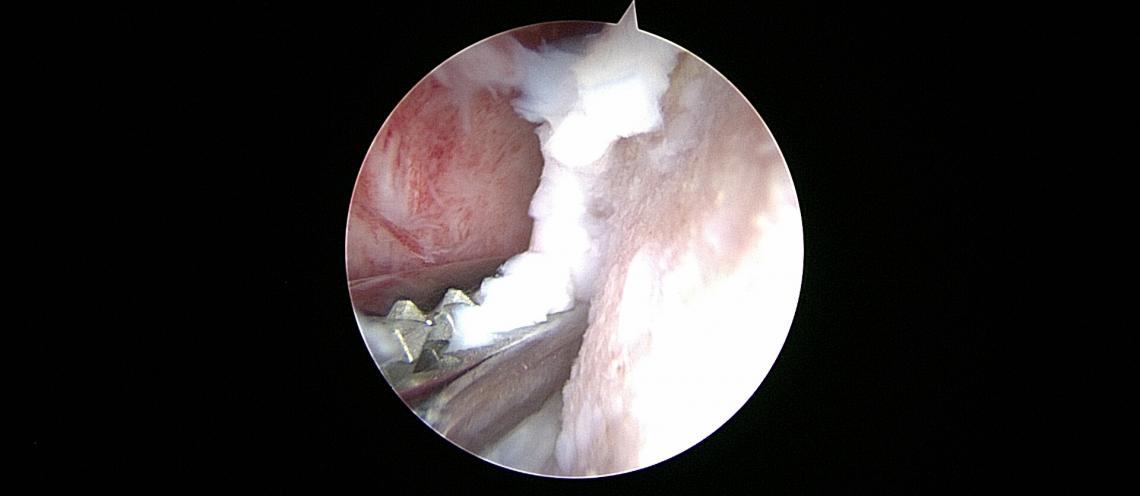

Top Photo: Thinking of the photo as a clock face, on the lower left side (about 7:30 p.m.) the arthroscopic grasper has a hold of the unhealthy cartilage as Dr. Rochat proceeds to remove it from Tripp.

Bottom Photo: This photo is a screen shot of a digital image taken of Tripp’s shoulder area. Thinking of the circle as a clock face, it shows healthy cartilage on the humeral head from 10:30 p.m. to 6 p.m. The vertically oriented cigar-shaped white area is the edge of the unhealthy cartilage that Dr. Rochat removed.

“When Tripp was diagnosed with OCD in his left shoulder, our veterinarian recommended Oklahoma State University,” Traw said. “It was our first time coming to the Veterinary Medical Hospital. I work for the Humane Society of the Ozarks and knew the veterinary college had a wonderful program. We had a great experience. I had researched the condition so I had many questions and Dr. Rochat answered them all before Tripp’s surgery. The veterinary students assigned to Tripp’s case were great. They would call me twice a day to give me an update on his condition. I appreciated that a lot.”

According to Dr. Rochat, the Veterinary Medical Hospital sees two to three OCD cases a year.

“OCD can affect many joints, including the shoulder, elbow, hip, knee or ankle,” he said. “It is fairly straightforward to diagnose and treat. A puppy will become lame for no apparent reason. When we examined Tripp, he showed signs of pain in his shoulder and a radiograph (x-ray) revealed a defect in the humeral head (the bone in the upper arm) where the flap had developed. Using an arthoscope, we removed the cartilage flap and scraped away the underlying unhealthy bone. After four to six weeks of crate rest, Tripp should be good to go.”

“The crate rest was hard because Tripp is still a puppy,” said Traw. “Dr. Rochat continued to answer even more questions during Tripp’s recovery process. He was one happy puppy when he was released to play with his two dog brothers. And as a bonus, Tripp now loves his crate and naps in it off and on during the day and sleeps in it at night. Prior to surgery, he wasn’t completely housebroken and now he is. Two positive things that came from surgery in addition to having a healthy puppy!”

“Tripp’s prognosis is good,” added Rochat. “It is best to treat OCD early before arthritis sets in. If your puppy is showing signs of lameness, don’t think it is just ‘growing pains.’ Take your dog to your veterinarian because your dog could have OCD.”

For more information about Oklahoma State University’s Veterinary Medical Hospital, visit http://cvhs.okstate.edu/osu-veterinary-medical-hospital.