Five Things You Should Know about Anaplasmosis This Fall

Monday, September 17, 2018

Every fall, several cases of the cattle disease anaplasmosis are usually seen in this region. Here are the top five things cattle owners should know about the disease in case it rears its ugly head again this year.

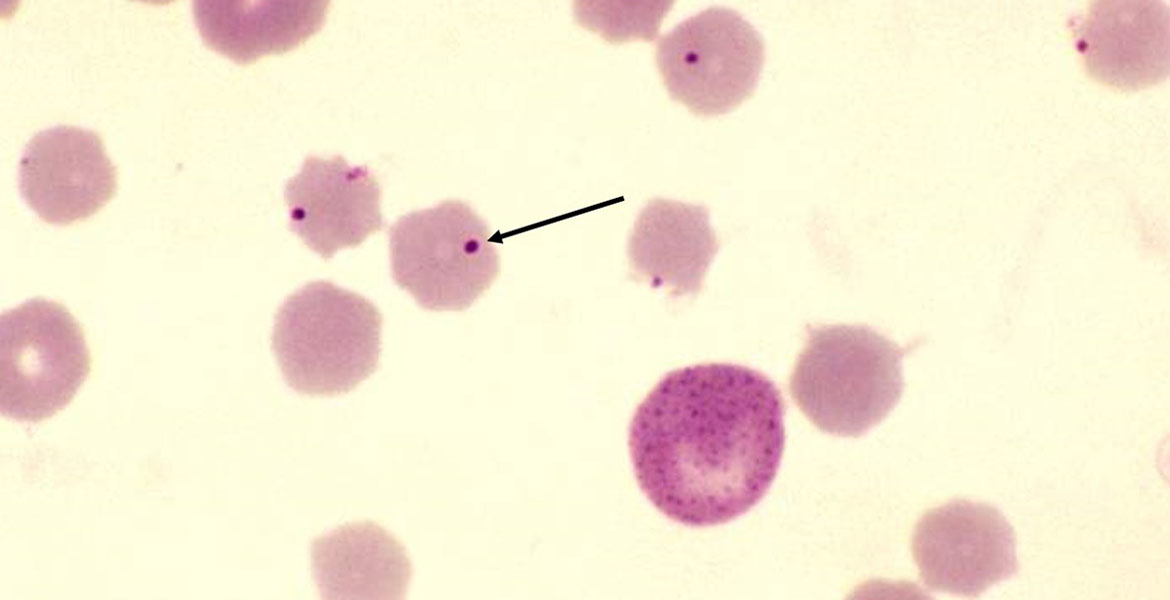

- Anaplasmosis is caused by a bacterial organism that infects the red blood cells but

doesn’t directly cause damage to the red blood cells. Rather, it causes the body to

recognize the red blood cells as foreign and the animal’s body itself kills the infected

cells, causing anemia. This results in the inability to transport oxygen, so the organs

and tissues fail. Initially, affected cattle may simply be noticed standing off alone

or not coming up to feed. Occasionally, an animal is found down and unable to get

up or is simply found dead. Middle aged to older cattle are more often affected than

young.

- It is transmitted by blood-sucking flies and ticks. Anaplasmosis can also be transmitted

by needles and other processing equipment. Measures can be taken to control ticks

and bloodsucking flies, but it’s nearly impossible to eliminate these as contributors

of risk. It is, however, within our power to control the transmission our equipment

causes. Disinfecting castration knives, dehorners, tattooing pliers and other equipment

that contacts blood can stop transmission from one animal to the next. Changing needles

after every animal is perhaps the most important control measure. Research has shown

that, after contacting blood from an infected steer, a single needle is able to infect

animals up to the tenth animal through the chute afterwards.

- Treatment can be successful. This organism can be killed by antibiotics in the class

of tetracyclines. No injectable antibiotics, however, are labelled for use in treating

anaplasmosis, so a veterinarian’s input is required for proper treatment. For cattle

who are severely affected, weak, or down, the prognosis for recovery is poor.

- A critical component in the recovery of any animal from anaplasmosis is that they

be handled quietly and calmly. Any sudden stress can cause them to decompensate for

the lack of oxygen in their blood and they can die instantly. When attempting to get

cattle up to treat them, they should be walked very slowly and quietly. I actually

recommend to my clients, whose herds have had a history of anaplasmosis that, if they

ever find a weak or down cow, they approach her slowly and look at the color of the

corners of her eyes or the inside of her vulva (for bulls, the inner portion of the

sheath works in all but black bulls). If the color is very white or has a yellowish

tinge, anaplasmosis could very likely be the problem. Then, when they call me, I know

that this is an animal that perhaps I should have the owner treat himself/herself

because if I drive up as a stranger in a strange truck, I may cause more harm than

good. This is a great example of a situation where an active, engaged relationship

with your veterinarian can be extremely helpful.

- Prevention is possible through insect and tick control and proper needle and equipment management but there is more that can be done. There are products that can be used in feed to reduce the numbers of organisms in the blood and prevent disease. New regulations activated in 2017 now require a Veterinary Feed Directive (similar to a prescription) from your veterinarian in order to use these. It’s worth a conversation with your veterinarian about your herd’s risk level for anaplasmosis to decide what types of preventative measures make the most sense for you.

We have many things to be thankful for here in Oklahoma, but we do have a slight setback in that we are in an environment that favors infectious cattle diseases like anaplasmosis. Be sure and discuss the control of this and other infectious diseases with your herd veterinarian.

by Meredyth Jones, DVM, MS, DACVIM (LA)