OSU researcher working to learn more about Chagas disease

Tuesday, April 30, 2019

Kelly Allen, MS, Ph.D., an assistant professor of veterinary parasitology at OSU’s Center for Veterinary Health Sciences (OSU-CVHS) whose research focuses on vector-borne diseases, is working to learn more about Chagas disease in Oklahoma. Chagas disease is a condition that develops in humans and dogs as a result of infection with the arthropod-borne parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Read more about Chagas disease and the Oklahoma survey work here: kissing bug research.

What is Chagas disease and how do humans and dogs become infected?

Chagas disease was first described by the Brazilian physician Dr. Carlos Chagas, who first documented the causative parasite, Trypansoma cruzi, in kissing bugs (Family: Reduviidae, Subfamily: Triatominae) and human patients in the early 1900s. Chagas disease is considered the most important parasitic disease in Latin America, and is responsible for millions of deaths annually and the greatest burden of disability-adjusted life years. Disease processes in infected humans and dogs are similar. Clinical manifestations range from unapparent to acute myocarditis and sudden death to chronic disease with eventual heart failure. Gastrointestinal tissue damage in chronic infections leading to megaesophagus and megacolon may also occur.

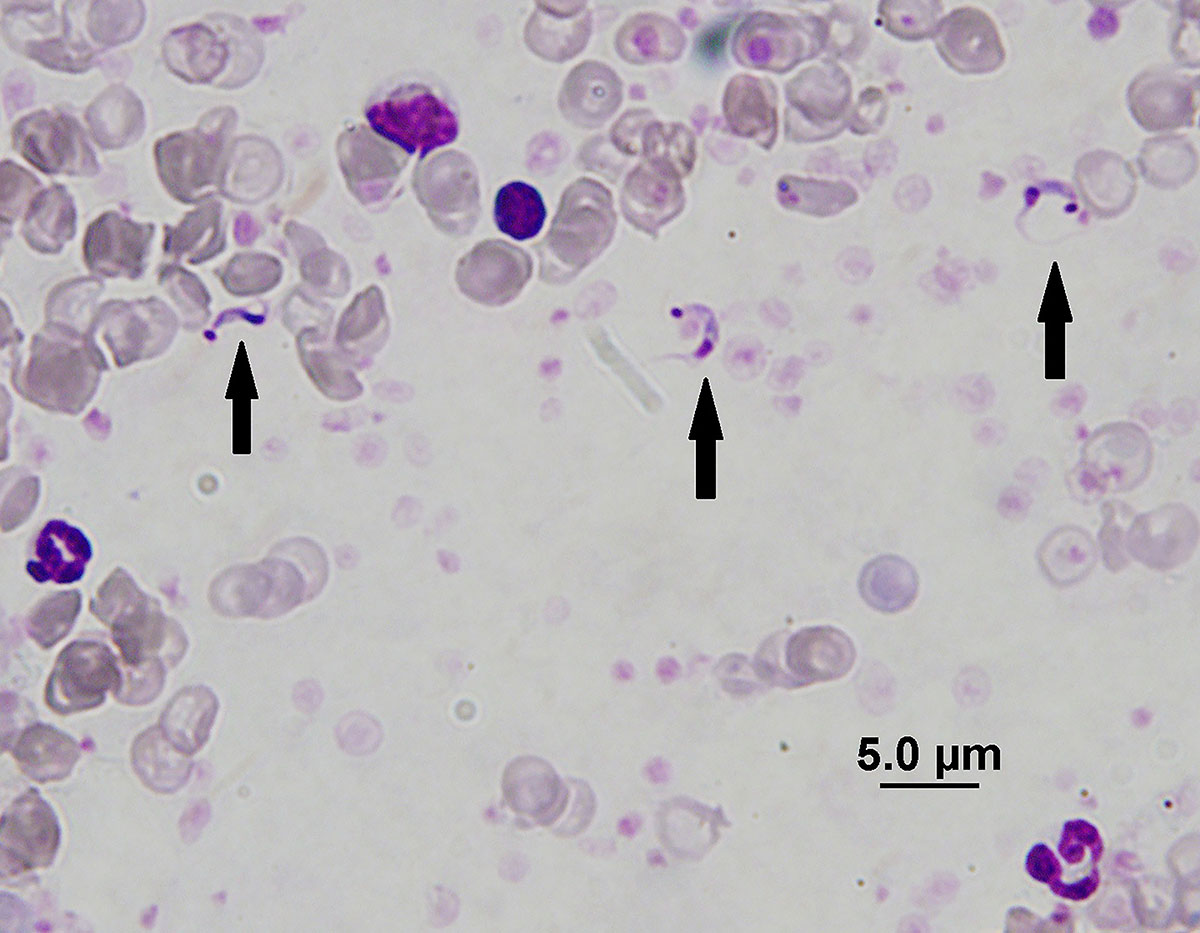

Humans and dogs are most commonly infected with T. cruzi when exposed to infected kissing bugs, although other routes including congenital, food-borne, and iatrogenic transmission are also documented. Kissing bugs feed on the blood of vertebrate hosts and harbor infective T. cruzi flagellated forms in their digestive tract. Transmission to humans, dogs, and other vertebrates occurs when fecal material deposited by an infected kissing bug is inoculated into the bite site, other wound, or mucosal membrane.

Is Chagas disease in the United States?

Yes. In fact, in 2018 the American Heart Association and the Inter-American Society of Cardiology issued a statement regarding Chagas disease to human healthcare providers in an effort to increase global awareness of the disease in areas outside of Latin America. In the United States, known wildlife reservoirs including armadillos, opossums, raccoons, and rodents are common in southern regions. At least 11 kissing bug species are present in the U.S., nine of which have been found to naturally harbor T. cruzi.

Fortunately, transmission of T. cruzi to humans is rare in the U.S. in comparison to Latin America due to generally improved domicile conditions, which reduce the potential for kissing bug infiltration and infestation. However, Chagas disease is regarded as a neglected tropical disease in the U.S. by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with inadequate funding vested into surveillance and other research efforts. Potentially confounding accurate prevalence estimations are the indeterminate latent phase of Chagas disease, which is lifelong in many patients and is associated with few clinical signs, and chronic disease manifestations occurring years to decades after infection (approximately 30 percent of humans and dogs). In Latin America, domestic dogs are considered reservoirs of T. cruzi infection and predictive of human risk; this potential reservoir role of domestic dogs in the U.S. remains unclear.

Trypanosoma cruzi survey work in Oklahoma

Dr. Allen is currently conducting survey work in Oklahoma to estimate the prevalence of T. cruzi infection in domestic dogs and kissing bugs within the state, as these data are historically lacking. She and her team have tested shelter dogs for antibodies against T. cruzi, indicating exposure, and have found a significant increase in seropositive dogs from 20 years prior in regions of eastern Oklahoma. The precipitous increase in canine seroprevalence suggests that Chagas disease is an under-recognized, emerging disease within the state. Veterinarians should consider T. cruzi infection as a differential diagnosis when evaluating canine patients from Oklahoma with heart disease.

At least two kissing bug species are found in Oklahoma, but T. cruzi infection prevalence in native insect populations is not known. Allen and her team are testing volunteer-submitted kissing bugs collected from across Oklahoma. Data are preliminary, but thus far they have detected T. cruzi by PCR in approximately 25 percent of the insects tested; canine and human blood have been molecularly identified in several specimens.

To learn more about Dr. Allen’s kissing bug survey work in Oklahoma or to submit a suspected kissing bug for Chagas testing, please visit the OSU-CVHS website for the Laboratory of Vector-Borne Parasitic Infections or email Dr. Allen directly at kissingbugandtell@gmail.com. A questionnaire and pre-paid postage label will be provided, and upon request, PCR results will be emailed. Use gloves, forceps, tongs, etc. to handle a suspected kissing bug. Do NOT handle bugs with bare hands.

MEDIA CONTACT: Taylor Bacon | Public Relations and Marketing Coordinator | 405-744-6728 | taylor.bacon@okstate.edu