Veterinary Viewpoints: Controlling Internal Parasites in Sheep and Goats

Tuesday, July 20, 2021

Spring through early summer in the U.S. is an ideal climate for internal parasites in such animals as sheep and goats. This year’s rainfall will promote larval hatching — and consumption by these small ruminants.

Gastrointestinal parasite management, especially for Barber pole worm or Haemonchus contortus, is a primary concern for all sheep and goat producers. Gastrointestinal parasites cause significant economic losses and are listed in the top three fatal conditions in sheep and goats. The development of dewormer resistance to nearly all three available anthelmintic classes makes control difficult and promotes alternative management strategies.

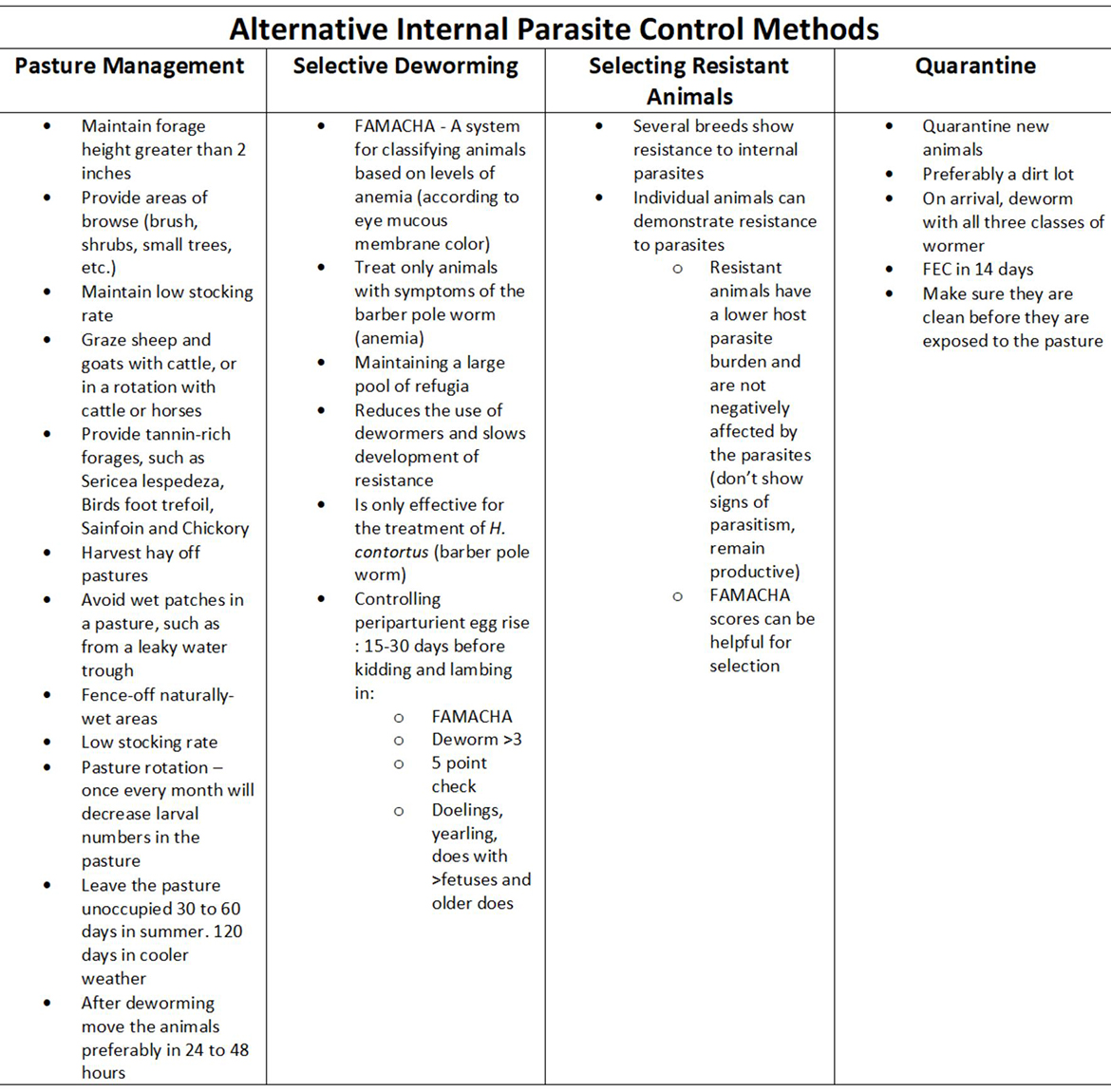

U.S. producers should work with their veterinarians to develop integrated approaches to parasite control by looking at the specifics of the host, the parasite and environmental interactions. The Barber pole worm thrives in warm and humid conditions and has the ability to undergo hypobiosis. In other words, it is metabolically inactive within the host during unfavorable weather conditions and emerges when conditions improve.

Infective larvae survive one to two months during hot summer months and more than four months during cooler, wet months. During kidding and lambing season, there is a rise in periparturient egg shedding in the feces that contaminates the environment. A good working knowledge of parasite life cycles is necessary to create control programs.

Three anthelmintic classes available in the U.S. are:

- Benzimidazoles (oxfendazole, febantel, fenbendazole and albendazole)

- Macrocyclic lactones:

- Avermectins (ivermectin, doramectin and eprinomectin)

- Milbemycins

- Cholinergic agonists:

- Imidazothiazoles (levamisole)

- Tetrahydropyrimidines (pyrantel and morantel).

However, only morantel, thiabendazole, fenbendazole, albendazole and phenothiazine are approved for goats. Thiabendazole and phenothiazine are not available. Other dewormers labelled for cattle and sheep may be used in an extra label manner in goats, provided you have a good valid client relationship with your veterinarian.

Dewormer resistance occurs when there is less than 95% reduction in fecal egg count 14 days after administration. Resistance has risen due to anthelmintics being used often, rotated too frequently, underdosed or using cattle labelled dose. Sheep and goats metabolize the dewormer quicker than cattle, so their dosage is higher than cattle.

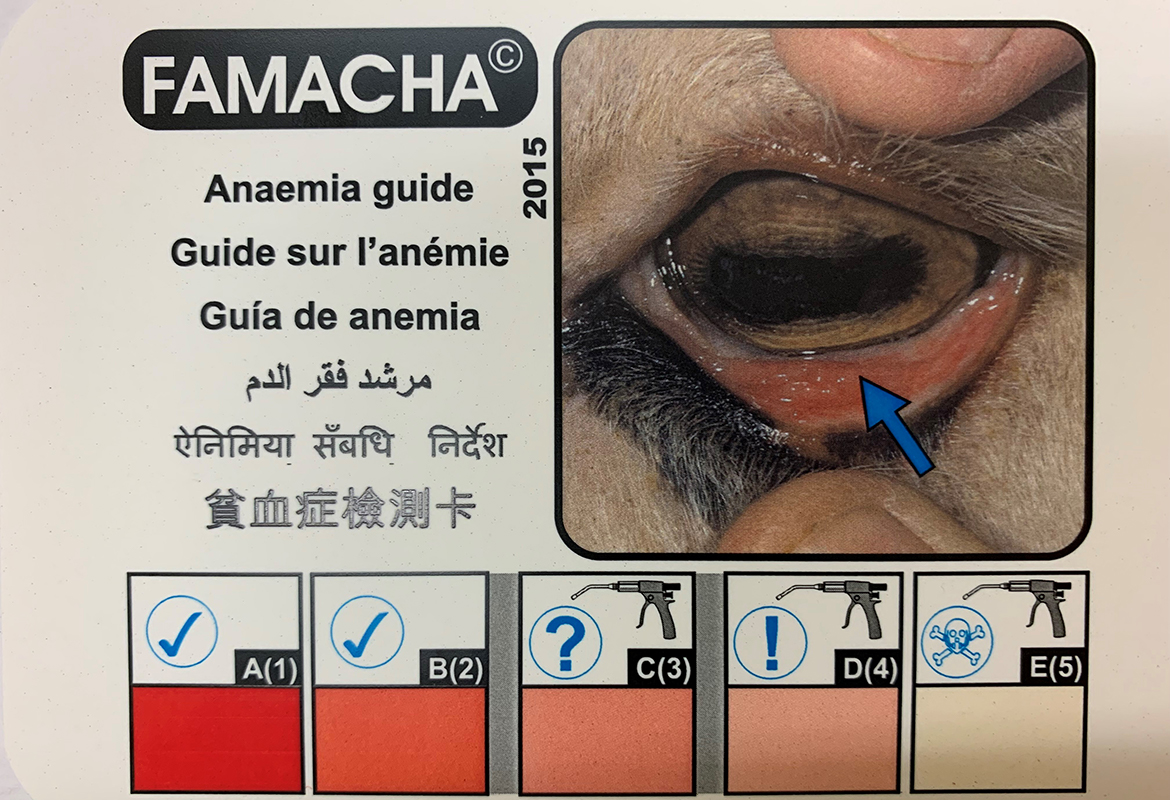

Control strategies must rely on the smart use of dewormers. This means treating only those animals that need to be dewormed and keeping a pool of susceptible worms, called refugia, in your animals. Refugia will mate with resistant worms to help prolong the use of anthelmintics. Smart deworming strategies for blood-sucking worms such as Haemonchus use the FAMACHA system to score the color of mucous eye membranes and evaluate anemia or blood loss. Another useful strategy for other worms is a five-point check (bottle jaw, hair coat, diarrhea, body condition and nasal secretion for nasal bots).

Periparturient deworming has been a mainstay of many internal parasite control programs. Deworming all the periparturient animals in early spring leaves minimal refugia in the pasture and can speed resistance. To provide enough refugia, don’t deworm 15% to 25% of animals not showing clinical signs. An Australian study recommends deworming periparurient doelings or yearlings, does carrying more than two fetuses, and older does, since they have a tendency to shed more eggs.

Due to increased dewormer resistance in goats compared to sheep, combining two or three classes of wormers at their appropriate dosages at the same time have been used with a fair amount of success. Selective deworming using a combination of different classes at the appropriate dosages at the same time is beneficial to promote refugia, but it can also promote resistance to all wormers available. Do not deworm your entire flock, but do check the mucous membrane around the eye, and deworm the animals greater than 3 on the FAMACHA score.

It is very important to use alternative control methods along with selective deworming with copper oxide wire particles, which have been shown to be significantly effective (70% to 90% FECR) against Haemonchus. Doses are low. Use caution with sheep as they are very sensitive to accumulating copper in the liver and are susceptible to copper poisoning. There is a very narrow safety range for copper requirements for maintenance in sheep at 10 ppm to toxic levels at 25 ppm. Check with your veterinarian prior to using copper oxide boluses in sheep and goats.

Small ruminant owners need to be aware that good nutrition is important to reduce the severity of internal parasitism. Literature reports the positive effect of supplemental protein, and in particular bypass or rumen un-degradable protein, on enhancing the resistance to internal parasites. Protein aids in tissue repair and provides essential amino acids to stimulate an immune response.

About the author: Lionel J. Dawson, BVSc, MS, DACT, is a professor, swine and small ruminant specialist at the Oklahoma State University College of Veterinary Medicine and an extension veterinarian at Langston University.

Veterinary Viewpoints is provided by the faculty of the OSU Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital. Certified by the American Animal Hospital Association, the hospital is open to the public providing routine and specialized care for all species and 24-hour emergency care, 365 days a year. Call 405-744-7000 for an appointment or more information.

OSU’s College of Veterinary Medicine is one of 32 accredited veterinary colleges in the United States and the only veterinary college in Oklahoma. The college’s Boren Veterinary Medical Hospital is open to the public and provides routine and specialized care for small and large animals. The hospital offers 24-hour emergency care and is certified by the American Animal Hospital Association. For more information, visit https://vetmed.okstate.edu or call 405-744-7000.