Putting on a happy face: Exploring the science behind surface acting

Monday, November 27, 2023

Media Contact: Terry Tush | Director of Marketing & Communications | 405-744-2703 | terry.tush@okstate.edu

When the server at your favorite restaurant stops by to take your order, what are they really thinking? Did they receive some great news earlier in the day that made their smile genuine? Or has it been one of those days where everything that could go wrong has gone wrong, and they are hiding their discontentment behind a forced smile?

Often, it’s hard to tell because every employee on some level fakes their observable facial or bodily displays at the workplace. Known as surface acting, everyone engages daily in what is one of the most common types of emotional labor.

Many decades of research have shown that surface acting is detrimental to employees. Often, the discontent spills over from work to home, where it can lead to insomnia, fatigue and even marital issues.

“Most jobs have some element of this, and we know already from years and years of research that it can take a large toll on people over time if they don’t have the coping mechanisms,” said Dr. Anna Lennard, associate professor in the Department of Management for Oklahoma State University’s Spears School of Business.

“The literature has largely argued that people go home, recharge and come back the next day and do it all over again. Employers haven’t taken it upon themselves to think, ‘What are the ways we can help employees?’ Or, ‘What are ways that people can recover?’ Or, ‘If they do recover, do they get over it? What happens when they leave work?’”

Lennard and co-authors Dr. Amy Bartels (College of Business, University of Nebraska-Lincoln), Dr. Brent Scott (Eli Broad College of Business, Michigan State University) and Dr. Suzanne Peterson (Thunderbird School of Global Management, Arizona State University) tackled that subject in their recently published article, “Stopping Surface-Acting Spillover: A Transactional Theory of Stress Perspective” in the Journal of Applied Psychology.

Studies show various instances where surface acting at work can lead to harmful outcomes at home, Lennard said. One example is when employees are surface acting at work, it can lead to inauthenticity at home, which is detrimental to both employees and their spouses.

“What we ended up finding is that when you need emotional labor at work, you leave feeling very depleted,” Lennard said. “So, you’re fatigued, you’re emotionally exhausted and that carries over to your interactions with your family at home. So, you don’t stop surface acting when you get home.

“That’s one of the main problems we looked at, and that’s really sad. What can be done for people to pull themselves out of this? It’s not fun just to think about ways that this is really terrible for people. It would be great if we could come up with some actual interventions that would help people.”

Lennard said the researchers focused on two different points of interaction. The first focus was on what employees can do at work to manage the depletion that comes from surface acting, which involves reframing the surface acting of the employee. There are good and bad stressors that all employees deal with daily: 1, hindrance stressors and 2, challenge stressors.

An example of a hindrance stressor is when an employee feels overloaded at work and has trouble completing their work assignment. It interrupts their work goals and interferes with their work growth.

Challenge stressors are opportunities for growth in the job (such as being asked to give a speech, performing well and growing in that area). Although it is subjective, the employee decides which challenges can be beneficial.

“If you can get employees to reframe surface acting as a challenge stressor, seeing it as something they can grow from and they can learn from, that’s good,” she said. “If they see that the more I engage, the more I’m actually going to enjoy this conversation and the better off it’s going to be for everyone.”

The second interaction involved asking the employee’s spouse to participate in an intervention around social support with them. The researchers broke it up into two conditions: 1, asking the spouse to push past what the employee was saying emotionally when they arrived home from work and trying to get them to talk about how they really felt, and 2, asking the spouse to act like they normally would to the employee, leaving them alone to deal with their feelings.

“So, if employees aren’t able to reappraise surface acting while at work, then having a spouse who really pushed past those inauthentic behaviors and provided social support allowed them to recover and it also fixed the issues within their marriage that can develop from this,” Lennard said. “The spouse’s relationship satisfaction increased, and the employee was also able to recover from surface acting and not carry those effects over to the next day.”

Lennard said there is no escaping surface acting in the workplace, as everyone does it, but seeing it as a growth experience can be beneficial.

“I think encouraging employees to see the positive challenges in the surface acting that they’re doing is one of the benefits,” she said. “There are ways that you can personally develop from it and just with some very light reframing of the way you see your job and your role, you can really make it a much more positive experience for yourself at work and minimize a lot of the negative effects.

“You can also use it as an opportunity to develop a better relationship with your spouse and limit the negative impact that this type of emotional regulation can have on your whole life.”

Story by: Terry Tush I Discover@Spears Magazine

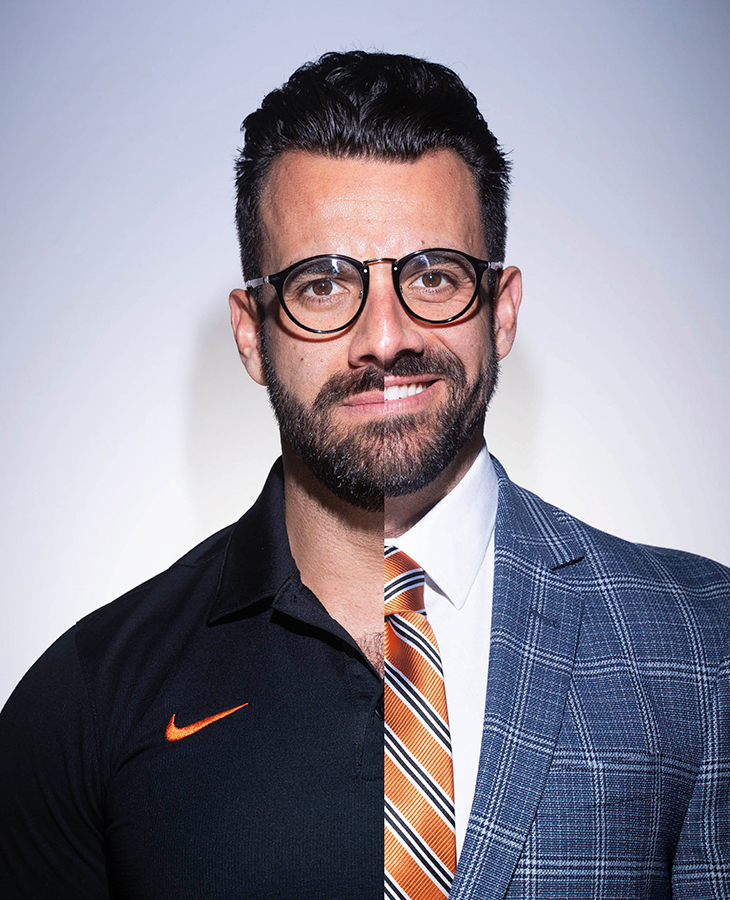

Photos by: Adam Luther