Triumph over tragedy

Monday, July 27, 2020

Journey leads Spears student from pain and healing to hope and determination

Visiting Munich, Germany, in the fall means a trip to the world-famous Oktoberfest, the huge celebration where a nation comes together to share its love of beer. For Cindy Crenshaw-Martin, vacationing in Munich with friends in 1980, the fun she expected walking through the festival’s main entrance vaporized before it began. Instead, fire and carnage would change the course of her life.

Crenshaw-Martin graduated from Oklahoma State University this spring with a bachelor’s degree that she has worked for, off and on, for nearly 40 years. She’s among college students often described as nontraditional because they may be working on their degree online and/or part time or because they are considered older than the average student. The 61-year-old is nontraditional in many ways besides her age — most notably because of her long, often difficult journey to get where she is today at the Spears School of Business.

“Two of my three kids are college graduates, and they’re all successful,” Crenshaw-Martin said. “It was my oldest son who encouraged me to go back to OSU, and now I’m really thankful to be here.”

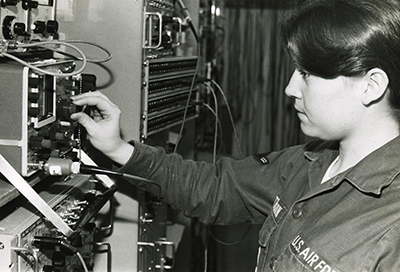

Raised in California, Crenshaw-Martin wanted to go to college, but her family couldn’t afford to send her. One option was military service, which Crenshaw-Martin saw as a chance to qualify for the GI Bill and as a way to see some of the world. In 1977, she joined the Air Force and attended tech school to learn to maintain microwave communications systems. She was 19 and eager for adventure.

The Air Force allowed her to pick her station, and she chose Hahn Air Base in West Germany, arriving there in December 1978. As the 1970s ended and the ’80s opened, politically charged environments raged throughout the world. U.S. embassy personnel in Iran were taken hostage in 1979, while in Europe protestors often marched in opposition to the presence of American nuclear weapons. Crenshaw-Martin remembers occasional bomb threats at American military bases, but she said she never felt threatened.

In September 1980, Crenshaw-Martin and fellow airmen from Hahn, including her husband at the time, traveled to Munich for a five-day leave. It would be her last chance to see some of West Germany before she shipped back to the United States in December. The group visited historic sites and on their third night headed to the Oktoberfest. As they walked into the festival entrance underneath the greeting “Willkommen Zum Oktoberfest,” a tremendous explosion ripped through the crowd.

“When we were walking in, that’s when the man set off the bomb in a trashcan,” Crenshaw-Martin said. “There were over 200 hurt, 13 killed, including the terrorist. I was so close to the blast that the fire burned my hair, my eyelashes.”

But burns were not her worst injuries. Bomb fragments severed Crenshaw-Martin’s left leg below the knee and shattered her right leg. She suffered cuts to her face and head while shrapnel nicked her spinal cord. The Americans with her, including her husband, received less serious wounds with one, amazingly, unhurt.

“I wasn’t supposed to make it, but God had other plans,” Crenshaw-Martin said. “The Air Force called my family and said, ‘You need to come,’ because they just assumed I wouldn’t make it.”

She was told a taxi driver saved her life that night by applying tourniquets to her legs and carrying her to an ambulance. From a Munich doctor’s “miraculous” work in the hours after the bombing to the next nine months of numerous operations and recovery, Crenshaw-Martin’s life was in the hands of surgeons, nurses, physical therapists, counselors and experts in prosthetics.

The terrorist was identified as a German rightwing extremist. Investigators concluded he was not a suicide bomber, but his device detonated prematurely. Authorities also believed he acted alone until the investigation was reopened 34 years later, in 2014, when new evidence suggested he may have had accomplices, but no collaborators were identified. Though American military personnel were injured, they were not the targets. Investigators believe he was trying to spread chaos before upcoming national elections.

After being initially treated in military hospitals in West Germany and the U.S., Crenshaw- Martin was transferred to Oak Knoll Naval Hospital in Oakland, Calif., where healing and rehabilitation continued and where she began to learn how to walk again with prosthetic legs.

“The first man who built my legs was a Vietnam veteran who’d lost one of his legs stepping on a landmine, and he was just the most insane, fun person,” she said. “I came in contact with a lot of really positive people at Oak Knoll who worked hard to get me back up on my feet and get me back to living.”

Nine months after the bombing, Crenshaw- Martin walked out of Oak Knoll with the help of crutches.

“I literally walked out, but I needed the crutches because I have paralysis on the right side from the spinal cord being nicked by shrapnel, but I didn’t care,” she said. “I was just happy to be alive and to have come through all the surgeries and then the work on my legs.”

After her release from the hospital, Crenshaw- Martin received a medical discharge from the Air Force, and the next phase of her life loomed. Her first mission was to travel, and she set out on two cross-country road trips, one with a friend and one a 10,000-mile solo trip.

It was during her solo trip while visiting an aunt and uncle in Ponca City, Oklahoma, that her uncle suggested she consider going to school at OSU. After a campus visit, she enrolled and, in the fall of 1983, the 25-year-old freshman and veteran began classes in the College of Business Administration. A year later, she married for a second time and the couple started a family, which meant struggling to balance family and school while helping with her husband’s business. She eventually left OSU to focus on raising her three children.

“I loved being an at-home mom, and I was very active in the kids’ schools,” she said.

"I don’t want evil to win, so if I can help other people see that blessings are always around the corner, then good triumphs over evil."

In 2007, she re-enrolled at OSU for two semesters but quit again because of the cost, believing she no longer qualified for veterans’ educational benefits. Her oldest son, Jason Crenshaw, an OSU graduate and a veteran who served in Iraq, encouraged his mom to finish her degree and to use her experiences to help a new generation of wounded veterans.

“I want to be able to encourage veterans to look at how many blessings they have and how important their lives are,” Crenshaw-Martin said. “My son, who is a veteran also, planted the seed and gave me the reason to go back. He said, ‘Mom, can you think about going back to school so that you can help veterans, because too many are killing themselves?’”

When Crenshaw-Martin contacted the Department of Veterans Affairs to find out if she was eligible for education benefits, she was told no. She was referred to a VA vocational rehabilitation counselor who notified her that because of her injuries, she actually did qualify for assistance. The doors to the OSU Spears School of Business opened to her, and she returned in the fall of 2018, needing 39 hours to complete the degree she started in 1983.

She was a university student again while her children were grown up and starting their own families, but that didn’t mean going back to school, at age 60, was going to be easy. She had a fear that students younger than her own kids wouldn’t accept her, but Spears students made her feel welcome. “They’re just phenomenal,” she said.

She also continued taking classes through the illness of her third husband, Terry Martin. Martin had been stationed at Hahn Air Base at the same time she was, though they didn’t know each other. Cindy, divorced from her second husband, met Martin through an online Air Force veterans’ group. The two married and spent time touring the country, including trips on Martin’s Harley- Davidson, and traveling to Europe where they visited Munich and the site of the Oktoberfest bombing. Martin’s health deteriorated after a liver transplant and open-heart surgery, and he died last year.

Crenshaw-Martin said she often did homework in her husband’s hospital room because she was determined to finish her degree.

“I was just not going to quit, because I’ve quit before,” she said.

Crenshaw-Martin wants to volunteer to help injured veterans recover from traumatic injuries, just as others helped her. After graduating this spring, and once the COVID-19 pandemic that marred her senior year and that of more than 1,000 other Spears Business seniors is no longer a threat, she plans to volunteer at the Oklahoma City VA Health Care System, where she has spent so much time over the years receiving care.

“I want to encourage others to believe that no problem is insurmountable,” she said. “When I would start thinking that I had it bad, I would always meet somebody who had it worse but was mentally strong and doing something for others. I don’t want evil to win, so if I can help other people see that blessings are always around the corner, then good triumphs over evil.

“It’s kind of like when you drop the stone in the pond and the ripples go out and intersect with others. I think goodness grows like that.”

With the world beginning to return to normal in the wake of the coronavirus crisis, Crenshaw-Martin brings an uplifting perspective on all that happened this year. She had a difficult last semester in school, not only because of the coronavirus and because her final courses were so difficult, but she also struggled to keep a positive attitude while looking after her father, who suffers from dementia. And after his nursing home was locked down, the pressure of not being able to see him and not being able to see friends was almost too much.

But Crenshaw-Martin wouldn’t let the virus, classes or her postponed commencement ceremony break her. After all, she had come through something so much worse.

“From that moment (of the bombing) on, every day has been a blessing to me, because, against all odds, I shouldn’t have made it,” she said. “I have an appreciation for life and even when there are hardships, because once we get through the hardships, the good things mean more.”

MEDIA CONTACT: Jeff Joiner | Communications Coordinator | 405.744.2700 | jeff.joiner@okstate.edu