OSU architecture students help a community in South Africa overcome a complicated past

Monday, January 10, 2022

Media Contact: Kristi Wheeler | Manager, CEAT Marketing and Communications | 405-744-5831 | kristi.wheeler@okstate.edu

At the southern tip of Africa lies a country with a rich history, a vibrant culture, a widely diverse ecosystem and a more diverse population, in more ways than one.

South Africa is home to inland savannas, coastal beaches, lush winelands and dense forests. The country is also as ethnically and culturally diverse as its ecosystems. The majority of the population is of African tribal descent, roughly 80 percent. The other 20 percent is mostly comprised of people with European heritage and a small percentage of Asian or other backgrounds.

South Africa is a nation of extremes. While it is arguably the most developed country in Africa, the country is also home to some of the most impoverished communities on the continent. It’s a situation that can largely be attributed to a complicated past that continues to impact the lives of its 60 million citizens to this day.

But, it’s also a situation that a small community outside of Johannesburg called Soweto hopes to put behind them with help from an unlikely source — a group of architecture students from Oklahoma State University and a seismic shift in the design of a fire station.

We want something that invites the community in and develops relationships both from a personal and professional - Rodney Eksteen

The Past

In the early 20th century, as South Africa began to gain an identity of its own under British rule, and an industrialization was taking place, racial tensions began to rise.

In 1913, a land act was passed by the minority, white-run government that marked the beginning of more than 90 years of segregation in South Africa. The 1913 Land Act forced Black Africans to live in reserves and made it illegal for them to work as sharecroppers, creating both physical and economic racial divides.

In 1948, the Afrikaner National Party won the general election under the slogan of “apartheid,” an Afrikaan word that literally meant apartness. The goal of the party was to not only create division between the white minority and the non-white majority, but to create division amongst the non-white majority. If black South Africans were divided along tribal lines, it would decrease their political power.

By 1950, the government had begun to build the framework of legalized segregation by passing the Population Registration Act which began classifying all South Africans by race: Bantu or black Africans; colored or those of mixed racial background; Asian (mostly Indian or Pakistani); and white.

During the next decade, a series of land acts were passed that set aside 80 percent of the country’s land for the white minority, created “pass laws” which required non-whites to carry documents that authorized their presence in restricted areas, allowed for the establishment of separate public facilities, and denied non-white participation in national government.

In 1959, the Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act was created, which established 10 Bantu “homelands,” thus completing the separation to black South Africans from whites and each other and enabled the government to claim that there was no black majority. This also instituted one of the most crippling systems under apartheid which enabled the government to forcibly remove black South Africans from “white” designated rural lands and relocate them to one of the 10 “homelands.” From 1961 to 1994, more than 3.5 million people were forcibly removed from their land and relocated with little to no means of earning a living.

By 1960, the anti-apartheid resistance movement had begun to gain momentum. The African National Congress had taken form and led the movement through non-violent demonstrations, protests, strikes, political action and eventually armed resistance. However, the government simply incarcerated most resistance leaders in an attempt to silence the “minority.”

Hostilities boiled over when a group of children in Soweto demonstrated against an Afrikaans language requirement, the police opened fire with tear gas and bullets. Hundreds of children were injured or killed, which drew international attention to South Africa. Economic sanctions and mandatory embargos from the United Nations followed. In 1989, Pieter Botha, the leader of South Africa, was pressured to step aside in favor of F.W. de Klerk.

His administration repealed most of the legislation that provided the legal framework of apartheid and in 1994, a new constitution took effect and led to a new governmental system that empowered non-whites and marked the official end of apartheid.

The Present

Although apartheid officially ended nearly 30 years ago, there is still a palpable separation between the more developed areas of South Africa and the suburban areas, like Soweto.

Building construction, infrastructure and the availability of civil services like a fire station are all things that draw a recognizable line between areas in South Africa. These suburban areas are comprised of old “matchbox” houses that were built to house non-white workers during apartheid. The building materials and proximity to each other pose serious concerns and increase the combustibility of these communities.

The physical concerns are only a small part of the problem. In South Africa, the fire service is structured much differently. The fire service plays a more paramilitary role than that of a civil servant. In most cases, firefighters serve as part of a mandatory conscription set forth by the government. They provide the typical firefighting services, but are also asked to serve in crowd control during riots or demonstrations.

Also, fire stations are built more as warehouses than as parts of communities. They resemble military installations with barred windows and gates and serve as “storage” for fire equipment and personnel. There is little to no interaction between fire service personnel and citizens outside of response to emergencies. The fire station, fire truck and firefighters are seen as governmental entities and can unintentionally embody political strife that is taking place at the time and thus become the target of protests and violence.

It is a problem that fire safety doctoral student and native South African, Rodney Eksteen, recognized and vowed to change moving into the future. He has partnered with Associate Professor of Architecture Jeanne Homer and Jocelin Flank, a 25-year member of the fire service in South Africa, and is involved with the design and construction of fire stations in the Johannesburg area, to help solve that problem.

“1994 was a turning point for South Africa,” Flank said. “But to this day, the design and composition of fire stations don’t truly represent their communities.”

There continues to be a barrier between citizens of South Africa and fire service personnel, both physically and perceptively. The group agrees that a fire station, in South Africa, must serve as more than just a fire station. Yes, it must provide the services and help facilitate the duties of a fire station, but it must also become part of a community.

Homer then tasked her studio design students to help solve the problem. The students were given a set of goals and parameters and were tasked with designing a modern fire station that not only belonged in the community of Soweto, but would also help bridge the gap between fire service personnel and citizens. It’s a design that would help both sides believe that they were partners in the care and well-being of their community.

“For me, a fire station must be representative of its community,” Flank said. “Just because a location is impoverished or isn’t as developed doesn’t mean that they don’t deserve a fire station that can invoke a sense of pride and inspiration to be better and take better care of their community.”

Eksteen said in the U.S., firefighters command a level of respect because of a long standing history of community service and sacrifice.

“The history in South Africa is very different and somewhat tainted,” Eksteen said. “We don’t want a place where firefighters sit around and wait for something to go wrong. We want something that invites the community in and develops relationships both from a personal and professional standpoint.”

After countless hours of research, days of planning, and weeks of designing and redesigning, the students presented their work to Flank, Eksteen, Homer and a myriad of engineers, architects and fire service personnel. Each group critiqued and scrutinized designs from a multitude of perspectives. All giving their views on the architectural design, building construction and efficacy for emergency response.

“These projects will be scrutinized by engineers, architects and members of the fire service,” Homer said. “And, honestly, I think the students’ main goal is to make sure that Jocelin and Rodney are happy with the designs and the community integration aspects of their projects.”

The native South Africans were certainly impressed with the results of these students’ hard work and dedication to the project.

“I have a drawing of a fire station that we’re starting construction on this year, and it’s nowhere near what these students have produced in terms of look, integration of culture and what we want to see in a fire station,” Flank said.“These youngsters blew my mind!”

The Future

The idea seems so simplistic, a fire station that appears as though it belongs in and to the community and invites citizens in to learn from and develop relationships with the fire service personnel tasked with protecting them.

However, it is an idea that we as Americans might take for granted. We see a fire station as an integral and assumed part of a community.

Stillwater, Oklahoma, the home of OSU, has four fire stations that serve its almost 50,000 residents. In comparison, Soweto has two fire stations for a population of more than one million people.

“These students have touched on something that they may not truly understand how impactful it can be,” Eksteen said. “In the immediacy, they are awarded a grade based on their work, but long term, if someone picks up one of these designs and is inspired to create something that embodies the ideas they’ve included, it can truly make a meaningful impact in South Africa.”

The project has provided the opportunity for students to learn from and provide assistance to a community half-way across the world, and for a community to heal from a dark past and look toward a brighter future.

“This is going to be an eye opener for the city of Johannesburg,” Flank said. “It is something we should be proud of and brag about. Hopefully this will become the starting point for a wonderful partnership between Oklahoma State University and the city of Johannesburg.”

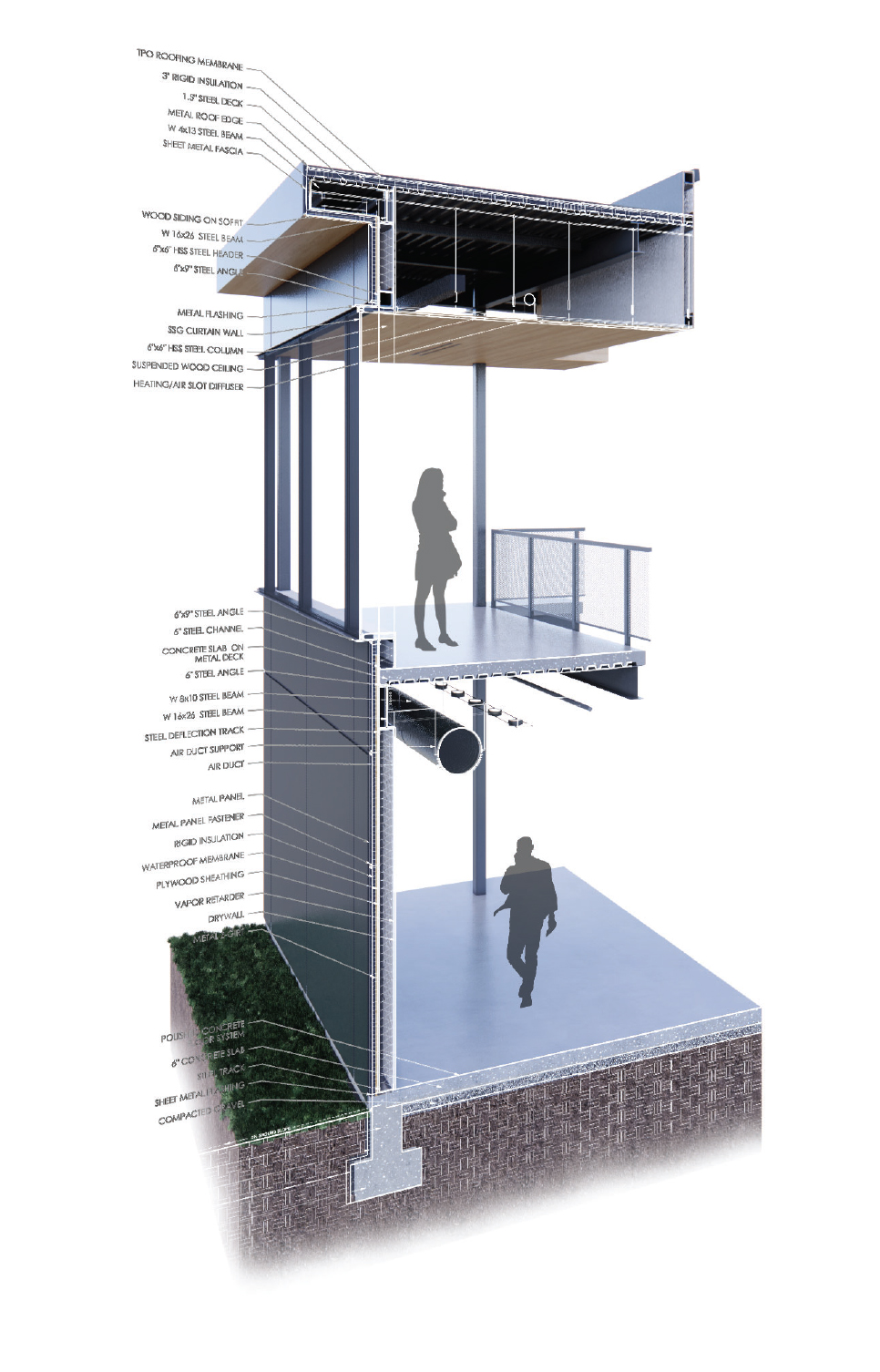

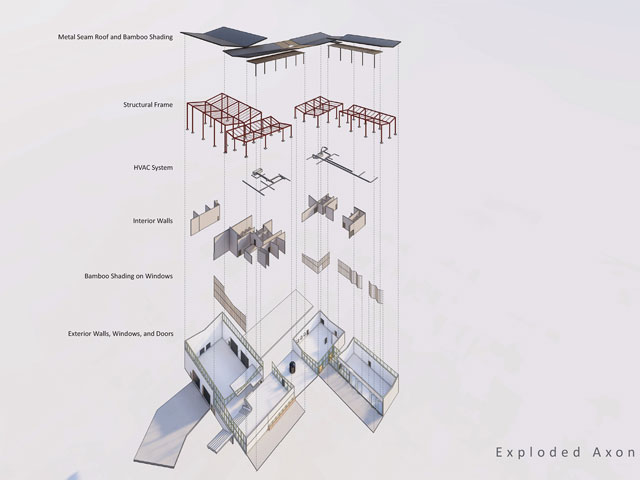

Architecture student's design of the fire station

Story by: Jeff Hopper | IMPACT Magazine