Strengthening Bonds

Wednesday, August 1, 2018

A new program created by graduate students brings families together with youth in juvenile detention to help change their lives

By Kim Archer

A teen gang member in juvenile detention broke into tears when he saw his 6-year-old brother for the first time in months.

“Seeing a 6-year-old with missing front teeth just run and jump into his older brother’s arms, it’s priceless,” OSU-Tulsa student Ashley Harvey said. “It’s very meaningful.”

Selected as prestigious Albert Schweitzer Fellows last spring, Harvey and Brooke Tuttle have instituted the Family Strengthening Project at the Tulsa County Family Center for Juvenile Justice.

Both are working on doctoral degrees in the Human Development and Family Science program at OSU-Tulsa.

They were among 14 Schweitzer Fellows in Tulsa and 260 across the country named to the 2017-18 cohort. The international fellowship was named for the late physician, humanitarian and Nobel Peace Prize recipient Albert Schweitzer.

As part of the fellowship, Harvey and Tuttle had to implement a yearlong service project addressing the root causes of health disparities in underserved communities. Their project focuses on strengthening young offenders’ bonds with their families.

Most of the kids ages 12-18 who pass through the Tulsa County detention center are headed to state facilities.

“These are kids who have committed crimes. They have made bad choices, but they are still just kids,” Harvey said. “I think this program helps them see that people haven’t given up on them and their families haven’t given up on them.”

Family approach

Many juvenile detention facilities across the U.S. are missing a critical part of the support net that helps teens get back on track — family relationships.

“We’re making progress across the country in how we treat juveniles. We’re less punitive now and more treatment- focused,” Tuttle said. “As far as we know, this is the first time that a family resilience program like this has been implemented in any juvenile detention center in the state of Oklahoma.”

Ryan Thomas, whose son Mitchell is among the first youthful offenders to graduate from the program, can attest to the power of the family element.

“Before this, Mitchell completed a nine-month rehabilitation program that didn’t work. It was nine months of wasted time,” he said. “This program did in six weeks what we couldn’t do in nine months.”

Thomas credited the element of rebuilding family relationships for providing his son with a strong foundation going forward.

“I see his smile. He has hope now. He has goals,” Thomas said. “Now he has plans for the future. And he knows he has his dad to back him up.”

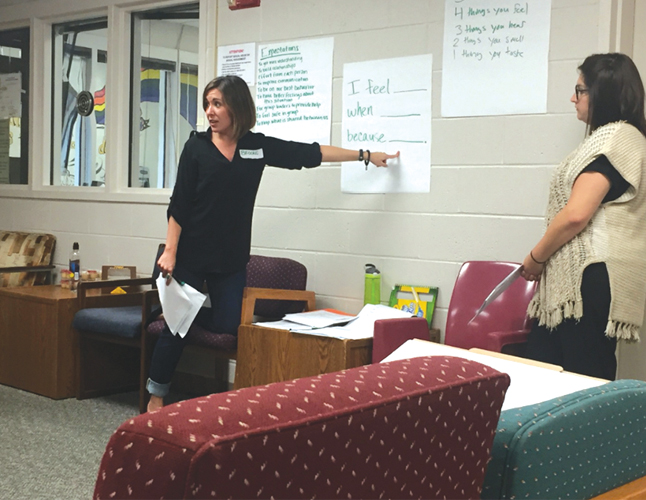

Every six weeks, the facilitators welcome a new group of four or five juveniles and their families to the weekly support group program to learn such life skills as communication and problem-solving strategies. Aimed at breaking the cycle of intergenerational crime, the project helps families rebuild relationships.

Often, the juveniles haven’t seen their families in months as they await court dates and adjudication. Each week’s group begins with families sitting down to a dinner together, something many haven’t done in some time.

“What we know from family science is that family matters,” Tuttle said. “In fact, it’s among the largest protective factors for kids who are at risk for delinquency. If you change one person in the family unit, the whole family system can change for the good.”

Better choices

Inside the Family Strengthening Project, Harvey and Tuttle have seen teens gain confidence and behave better as they learn life skills and reconnect with family.

“There is a big need for this in juvenile facilities,” said Rob Mouser, an OSU-Tulsa graduate student and the detention center’s clinical director. “We’ve seen hard-core kids — at least on paper — get emotional when they see their family. And the commitment from many of their parents has been amazing.”

He said the program is the first time most of the kids have worked on issues with their families.

“For a lot of kids, this is a wake-up call,” he said.

One young man who rarely spoke or made eye contact when he began the program became an ambassador and mentor after he completed it.

Harvey said the teen now shares his story with families and youth during their first group meeting. He also surprised Harvey and Tuttle by comforting a young boy who was crying because his mother didn’t show up for a session.

“It’s just amazing to see where he is now compared with where he started,” Harvey said. “He has a bright future.”

Harvey and Tuttle have identified funding to keep the program going and will continue in their facilitator roles.

“These are kids who haven’t made the best decisions, but they still have a lot of time to get it right. They just need the tools, the space and the support to make that happen,” Tuttle said. “It has been so exciting to see the direction that not only Tulsa is going, but hopefully the direction the state will go.”