Legendary legacy: How Coach Sutton's impact transformed OSU

Tuesday, September 1, 2020

Kendria Cost glanced out from her fish-bowl office at Career Services inside the Student Union, taken aback by the man lighting up the lobby beyond her window.

Eddie Sutton had that effect on folks, especially Oklahoma State folks.

“I looked up, and Coach Sutton was at the front desk,” said Cost, now the executive assistant for First Cowgirl Ann Hargis. “I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, Coach is here.’”

It was March 2002, 14 months after the plane crash that claimed 10 lives, eight associated with the men’s basketball team led by Coach Sutton, in a tragedy that crippled the community and resonated nationally.

The program and the school were changed forever, yet the games went on, as they do, and the Cowboys were leaving that day for the NCAA Tournament in Syracuse, New York. But first, Coach Sutton had a surprise stop to make, prompted by a letter from Cost’s father, simply tipping the coach off to one of his fans.

“I watched and a few minutes later they started pointing to me, and he started walking toward my office,” Cost said. “And he came into my office and he introduced himself — like the man needed an introduction — but he introduced himself, said he heard I was a fan and said he wanted to come and thank me. And he handed me a picture he had signed.

“In my brain I’m thinking, ‘This is a man who’s been through a terrible tragedy. He has left his office, he came to the Student Union, he found a parking place in the garage, he tracked me down, and he hand-delivered this to me.’”

That was Eddie Sutton.

And he will be missed.

Coach Sutton died May 23 at his home in Tulsa at the age of 84, leaving behind an adoring family with both immediate and extended members, including the OSU family who embraced the man for his greatness and despite his weaknesses.

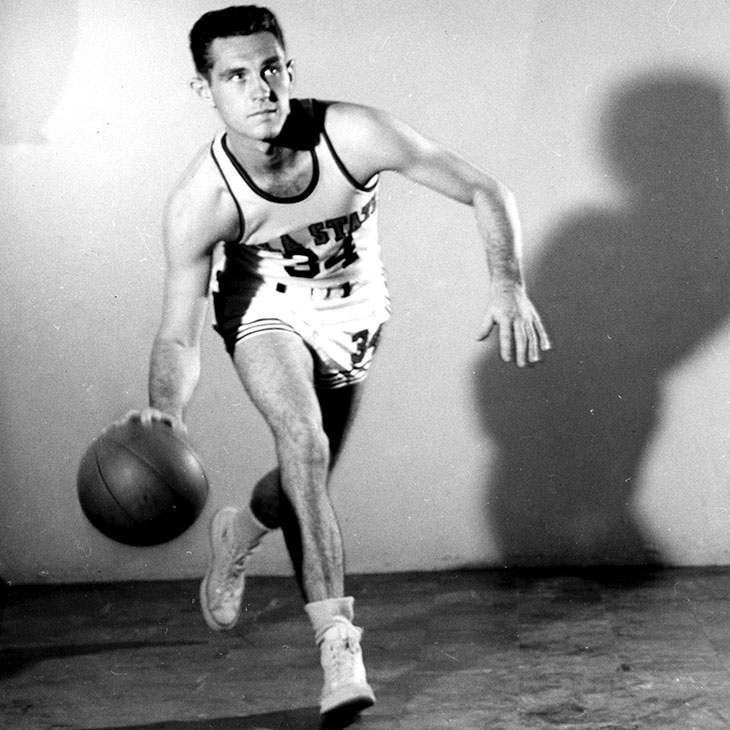

A native of Bucklin, Kansas, who journeyed to OSU to play for the legendary Henry P. Iba in the 1950s, Coach Sutton emerged as a legend himself in the years following his return to coach the Cowboys in 1990.

Coach Sutton won — immediately and a lot — yet success alone wouldn’t define his robust legacy at OSU. That emerges from how he impacted people, from players to fans, young and old, through an overflowing generosity of time and friendship.

And it’s reasonable to suggest the legacy grows still, every time a new stadium or business building or arts center rises on campus, considering the timing of the coach’s return to OSU and its people in need of a revival.

Connect the dots, and it’s easy to link Coach Sutton as the force that jolted to life the thriving Oklahoma State landscape that exists today — all across campus.

EDDIE THE BUILDER

Eddie Sutton earned a degree from Oklahoma State in 1958, worked one year as an assistant under Iba, his mentor, then embarked on his own career, amassing successes all along the way.

By the time he returned to coach the Cowboys in April 1990, the program offered little resemblance to the powerhouse he’d left more than three decades before.

During the 20 years that Coach Sutton piled up wins and accolades at Creighton, Arkansas and Kentucky, OSU spun through five coaches, managed only six winning seasons, finished in the top half of the Big Eight Conference only three times and appeared in the NCAA Tournament only once.

And basketball wasn’t alone in the athletic darkness. Football was on probation and soon to endure a winless season, leaving the school’s highest profile — and most financially important sports — irrelevant nationally. Even the proud wrestling program was shackled with NCAA probation.

Interest was down. Attendance was falling. Confidence was gone.

Athletics, and the entire university, needed something, someone, to believe in.

Enter Eddie.

The overhaul was swift. In Coach Sutton’s first season, 1990-91, the Cowboys went 24-8, won the Big Eight regular season championship and advanced to the NCAA’s Sweet 16. Soon, Gallagher-Iba was selling out.

And it was only the beginning.

In 16 years as the Cowboys’ head coach, Coach Sutton won 368 games — second only to Iba in OSU history — and led his teams to 13 NCAA appearances, two Final Fours, two regular-season conference titles and three league tournament titles.

Coach Sutton pumped life into the program. Into the university. Into Oklahoma State people.

And he pumped optimism into the future.

“We were in need of an infusion,” said Harry Birdwell, a former OSU vice president and athletic director. “When Eddie came, the facilities were an awful issue. Finances were an awful issue. And confidence needed a boost. He came at the perfect time.”

In many ways, Coach Sutton was the perfect fit. Oklahoma State pedigree. Confident. Caring. Uniting.

Columnist Berry Tramel of The Oklahoman wrote that Coach Sutton stood as OSU’s John Wayne. If the boots fit …

"He had the demeanor of a person who was genuine to the core."

“He was a guy from Bucklin, Kansas, for cryin’ out loud, who had no airs and was just as kind to the greatest and the least of fans," Birdwell said. "He really cared about people.”

And the people cared about Coach Sutton and what he was accomplishing, responding to his pitches at frat houses and community gatherings, anywhere folks would lend an ear, in an effort to stir up interest in his squad.

The success and revived optimism raised the roof on Gallagher-Iba literally, leading to a 2000 expansion that more than doubled seating capacity, from 6,381 to 13,611.

The name was still Gallagher-Iba, but the new addition was the house that Eddie built, featuring an atmosphere so charged it was dubbed “The Rowdiest Arena in the Country.” Students hoping to claim the best seats pitched tents outside in an area they dubbed “Camp Sutton,” and their hero often personally delivered pizzas to help them through cold nights.

All that spurred more hope and more building. And brought boosters — big boosters — including Boone Pickens and others. The vision for an Athletic Village, which seemed like a pipe dream back then, now stands nearly complete, with prominent names attached.

Boone Pickens Stadium. Michael and Anne Greenwood Tennis Center. O’Brate Stadium. Neal Patterson Stadium. Sherman E. Smith Training Center.

“When I became vice president at OSU, it was a fairly rare thing for a donor to OSU academics or athletics to give a million dollars or more to the institution,” Birdwell said. “As a matter of fact, back then you could count on one hand the number of people who gave a million dollars or more.

“Look at what has happened in the 25 years since.”

And not just with athletics. The campus profile has changed dramatically, with state-of-the-art buildings offering the latest in comforts and enhanced learning for students.

Oklahoma State needed a movement in the early 1990s. Eddie Sutton provided a shove.

Question: What might have, or might have not, happened if OSU had hired yet another middling basketball coach in 1990?

Burns Hargis considers athletics the “front door” for giving. Bring a potential donor to a game, let them experience the excitement and the fun and explain to them how they can be a part of it all.

“My flippant line always is, ‘It’s hard to get 60,000 people to show up for a math contest,’” Hargis said. “But time and time again, we’ve seen where the alums come back, they get excited going to the games. And maybe even start out supporting athletics.

“But slowly they’ll gravitate back to their roots, academy or leadership activities on campus.”

And they have gravitated, by the score.

“I’m so proud, because I’ve worked in athletics all these years, of the fact that the difference-making fundraising started with athletics,” said Larry Reece, a senior associate athletic director for development. “And it filtered over to campus and you see what has happened there. You see Burns Hargis able to have a successful billion-dollar campaign — at Oklahoma State. That’s unbelievable.

“And it all started in athletics. And I don’t believe it would have started if we didn’t have Eddie Sutton here, and we needed to double the capacity of Gallagher-Iba Arena. It made our people realize, ‘Wow, we can do it here. We can build great things here.’”

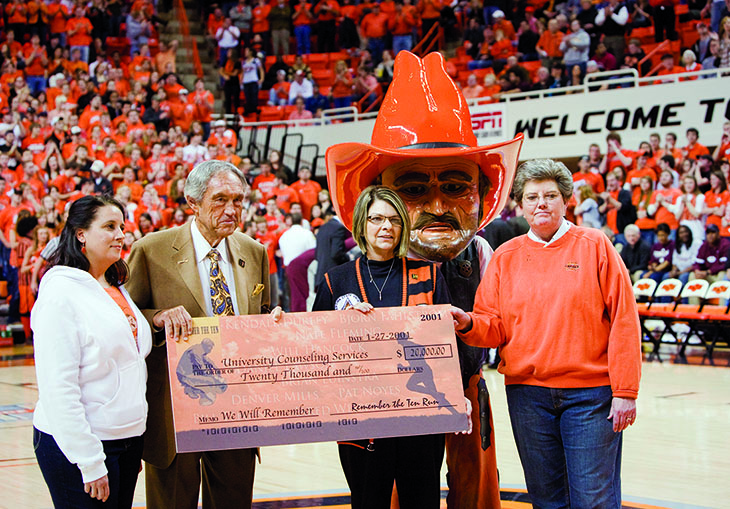

EDDIE THE HEALER

During the renovation of Gallagher- Iba Arena, the basketball coaches’ offices were transplanted to old Cordell Hall, just west of then Lewis Field.

It was there, on the chilling night of Jan. 27, 2001, a small group huddled in the northwest corner of the first floor, trying to grasp what to do next in the aftermath of tragedy. Not only had they lost dear friends when a plane went down in a Colorado field, creating unbearable grief, but families had to be notified.

There were offers to help with the calls, but Coach Sutton insisted on being the one to deliver the news.

“Eddie wanted to be the one who told moms and dads and wives,” said Birdwell, who was there that night. “And it was excruciating. But he knew it had to be done. And he had to do it out of relationship and respect and love for those guys.

“I’ll never forget the night. He was sensitive. He was honest. Sometimes in tragedies, it happens in such a blur that you may not sort of recognize the gravity. I think from the first instant, Coach understood that this was major news nationally, but it was a watershed moment for OSU.”

Not only that night, but in the days and weeks following, Coach Sutton seemed to hoist the school and the state on his shoulders, playing the John Wayne role to the fullest in navigating the tragedy.

“I don’t think I’ve ever been more proud of him than I was through that whole process,” said Eddie’s son Sean, then an assistant on his father’s staff.

"It was inspiring. I was in awe of his strength and courage to meet that head-on."

“And, really, his ability to pick himself up every morning and do whatever it took

that day to help the people around him, was pretty amazing to watch.”

Sean said the crash took a toll on his dad. Those were his friends and his players,

and he felt a responsibility as the man in charge. Eddie would say there wasn’t a

day that went by in which he didn’t think of those lost.

Amid it all, he still had a team to coach. And he somehow managed to direct a grieving young team on through the schedule, even earning an NCAA berth, where another round of cameras and microphones focused on him as the face of the program.

Eddie held up well. And he held up OSU with him.

“I think he knew that he needed to be strong and let the OSU family lean on him,” Reece said. “I think that took a toll on him, but I think that was something he wanted and was willing to do.

“I don’t know if we could have gotten through it if Eddie hadn’t been so strong.”

EDDIE THE GIVER

The Spady family was returning to Hinton from OU Children’s Hospital in Oklahoma City, where 11-year-old Caleb had endured an MRI and a checklist of meetings in another round of treatments for a brain tumor.

On his birthday, no less.

Nearing home, dad Ken Spady’s phone rang from the front seat. It was Eddie Sutton. He wanted to speak to Caleb.

The two chatted a bit, then the entire car was stunned at what happened next: Eddie broke out in song, maybe a little hoarse and gruff, but the best “Happy Birthday” Caleb ever heard.

“It was so perfect,” said mom Kim Spady. “It took his mind away from all the medical stuff we did that day, on his birthday. It was a hard day. And it brought his focus back to the things that he loved. And that’s what he loved the most, sports and OSU sports.

“We were all in the car together, and we all got to enjoy it and be a part of it.”

And the Spadys, who lost Caleb to that cancer in 2009, have never forgotten.

“The legacy that Coach Sutton left … just five minutes of his day, what an impact it had,” Kim said. “Think of all the five-minute gifts he did over his life, because I know there are many other stories.”

Eddie and Caleb first met through Coaches vs. Cancer, a program Coach Sutton helped launch in 1993 after Missouri coach Norm Stewart was diagnosed with the disease and the two sought to inspire a cause to help. Since its inception, coaches have helped raise more than $100 million for the American Cancer Society.

Beyond the fundraising, and spurred by Coach Sutton, OSU hosts young people dealing with cancer throughout the school year, with parties and inside access to the Cowboys and Cowgirls and their teams.

The events provide a needed distraction for kids dealing with cancer. Those involved say the encounters benefit both the patients and the athletes.

And again, it all started with Coach Sutton.

Cost couldn’t have known that day in her office at Career Services that she’d one day work closely with Eddie Sutton, but when given the opportunity to join OSU’s Coaches vs. Cancer group, she jumped, serving first as the co-chair and now as chair.

Eddie was so committed to the cause that he’d show up in Cost’s office with a legal pad, ready to take notes.

“He would say, ‘How can I help you and what would you like for me to do?’” she said. Then Coach Sutton would go do it.

“He would always call me before the season and give me a report. And it was kind of surreal, kind of like I was his boss or something.”

Coach Sutton always took time to connect with patients and survivors, writing notes or posing for pictures or even offering a song.

“I think really, I saw a side of him a lot of people didn’t see on the bench, with the scowl,” Cost said. “But he was really engaged.”

That was Coach Sutton’s secret, engaging with folks. Fans. Donors. The guy at the gas pump. A mother standing in line at the donut shop.

And he connected with his players, sometimes with tough love, yet love that almost without fail was recognized. Upon Coach Sutton’s death, players from throughout his coaching stops offered a flow of tributes about what he meant in their lives, most hailing his role in molding them into men.

When Daniel Bobik transferred from BYU to OSU, with a wife and newborn son and no scholarship, Coach Sutton pointed him to local business owners who might be able to offer a job to help pay the bills. The coach, recognizing Bobik’s strong LDS background, also connected him with longtime OSU professor Lee Manzer, who shares the faith.

“I think the biggest thing that anyone would say is that they knew Coach cared about them,” said Bobik, adding that he’s now carrying on that legacy as a high school coach in Arizona.

"He had a genuine love for people. And most of all he had a special love for us as players. And we could feel that."

EDDIE! EDDIE! EDDIE!

During the height of his popularity at OSU and well after, faithful fans of all ages chant his name.

That treatment, reserved solely for him in school lore, hints at Eddie Sutton’s legacy.

“I can never chant it,” Cost said, “and here’s why: I had so much respect for him I could never call him by his first name. I couldn’t do it. He was Coach.

“And he loved that. He told me once, ‘I just love it when they do that, it pumps me up.’ He was authentic.”

Authentically Cowboy.

And his legacy endures, in the trophies and the snapshots of him cutting down nets displayed inside Heritage Hall, and in all the shiny new facilities that may not feature his name but were clearly fueled by his impact.

“When it comes to the most beloved figures in OSU athletic history, he’s certainly on Mount Rushmore. And he may be the most beloved,” Birdwell said.

“I describe him as a guy who was disguised as a basketball coach, but he was a healer, he was a psychologist, he was a sociologist who brought people of all generations and ethnicities to believe beyond their wildest expectations.

“Eddie caused people to want to dream about things that they may have thought were ridiculous before he showed up. And he helped people make memories that they’ll never forget.”