Spanish flu hit an unprepared Oklahoma A&M campus in 1918

Thursday, September 3, 2020

Facing Down a Pandemic

It is surprising that so few casualties have been reported when considering the difficulty of teaching the student body the seriousness of the epidemic with which they were confronted. Not only did the students think the flu was a joke, but even the townspeople did not take the epidemic seriously until the cases began piling up out of all proportions.

Orange and Black, the OAMC student newspaper, Oct. 26, 1918

COVID-19 isn’t the first pandemic Oklahoma State University has faced in its 130-year history.

In 1918, an unprepared nation and Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College faced an invisible foe they never anticipated. The initial impact of the Spanish flu pandemic at the beginning of the year had been insignificant in Oklahoma.

The second wave struck the campus that fall. This virulent H1N1 flu killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide and about 675,000 in the United States between January 1918 and December 1920.

The fall semester began Friday, Sept. 6, with 1,753 students. Registrations remained strong in spite of World War I. The college served as a site for the Student Army Training Corps, which allowed young men to enlist in the army, begin their military training and take classes, often in engineering, which could help in replacing or repairing war-damaged infrastructure.

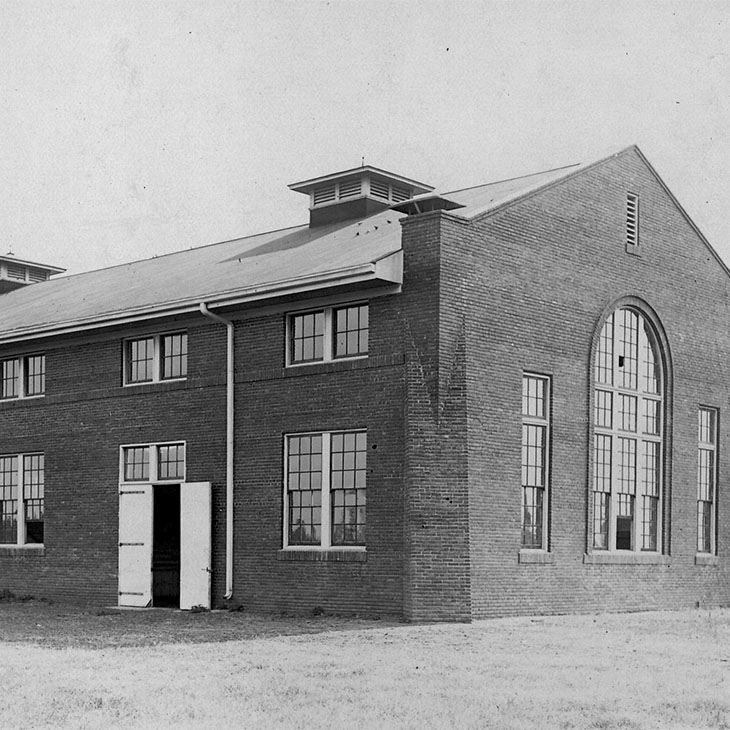

The SATC soldiers resided and ate on campus. The Boys Dormitory, designed for 120 students, housed 240 soldiers and the Livestock Pavilion became a barracks for another 250. The Women’s Building, which housed the School of Home Economics and served as the residence hall for female students, had kitchens and a communal dining hall with a capacity to serve 150. A temporary mess hall was constructed to serve another 350 men.

On Sep. 21, 1918, the first hint of a problem appeared at the bottom of the “Dorm Notes” column in the weekly student newspaper, Orange and Black: “A great many of the dorm girls left their windows open during the past week on account of influenza.” That same day, the college sent a large contingent of faculty, staff and students to the Oklahoma State Fair in Oklahoma City.

An announcement five days earlier in the Oklahoma City newspapers that the “Spanish Flu May Be Rampant Here” did not deter the college migration to this annual event. At the same time, Army officers assigned to the Student Army Training Corps arrived on campus from a number of different military posts, some of which were already experiencing the flu epidemic.

Lee Cochran, from Weleetka, Oklahoma, wrote OAMC President James W. Cantwell on Oct. 7, 1918, asking if “the Spanish Influenza has broken out in the college and that there was danger to students coming there.” He was recruiting college students and wanted to assure potential candidates and their families that it was safe on the Stillwater campus.

Randle Perdue, secretary to the president, responded immediately: “There are not more than four or five cases and every precaution is being taken to prevent the spread of the disease. We are not alarmed in any way.” In less than two weeks, the situation at the college would change dramatically.

On Oct. 6, Oklahoma City physicians expressed the opinion that “citizens were unduly alarmed” with the flu disruptions and there was “no reason for thinking that the disease will again break out.”

Five days later, reports of 19 deaths there prompted a general closing order citywide. A similar situation occurred in Stillwater with more than 40 student cases reported. The city Board of Health closed all public gatherings including movie theaters and churches.

Public schools shut down, and the college eliminated all social functions. The first home football game of the season, against the Haskell Institute team from Lawrence, Kansas, on Oct. 5, was the last game played for a month. Northeast Kansas was one of the epicenters of the Spanish flu outbreak, but no definitive connections traced its spread to the Haskell football team.

The team played again Nov. 2 against Central Normal (now the University of Central Oklahoma) from Edmond. The football team continued to practice even though more than half of the players suffered from the flu.

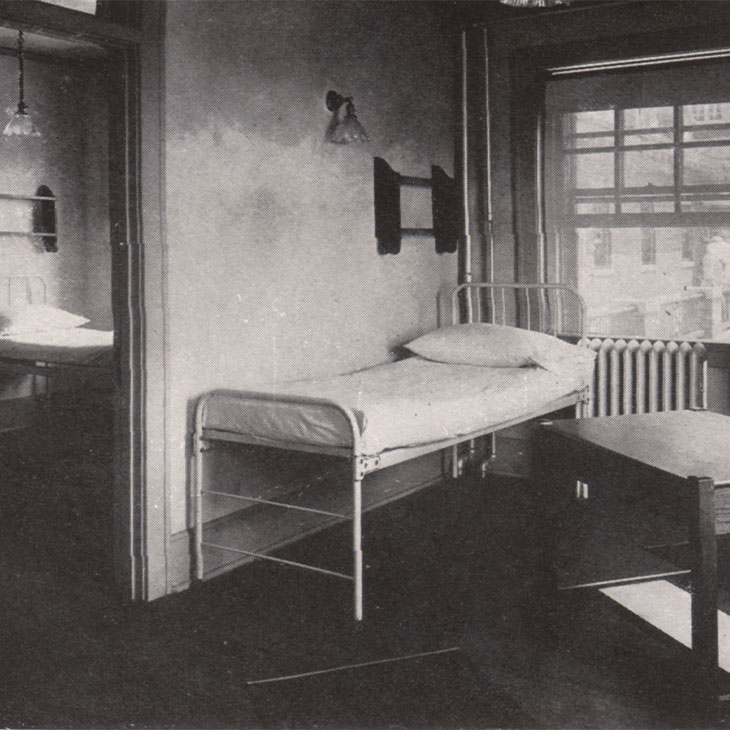

By mid-October, the dormitories on campus were serving as hospitals. Healthy and recovered students cared for the sick. A wood-framed home, first built for the college president in 1893, served as the first hospital for the SATC men before the entire Boys Dormitory was repurposed.

Women faculty, staff and seniors provided primary care at the Women’s Building under the direction of Ruth Michaels, dean of Home Economics. Classes were suspended to free teachers and students for medical duty. They delivered medicines, picked up “sick” trays in the dining hall, ran errands and even gave up their own beds to allow visiting relatives a place to stay.

These nurses also cared for the SATC men. A few students moved into town to be closer to local doctors. While done with the best of intentions, many of these actions facilitated the spread of influenza.

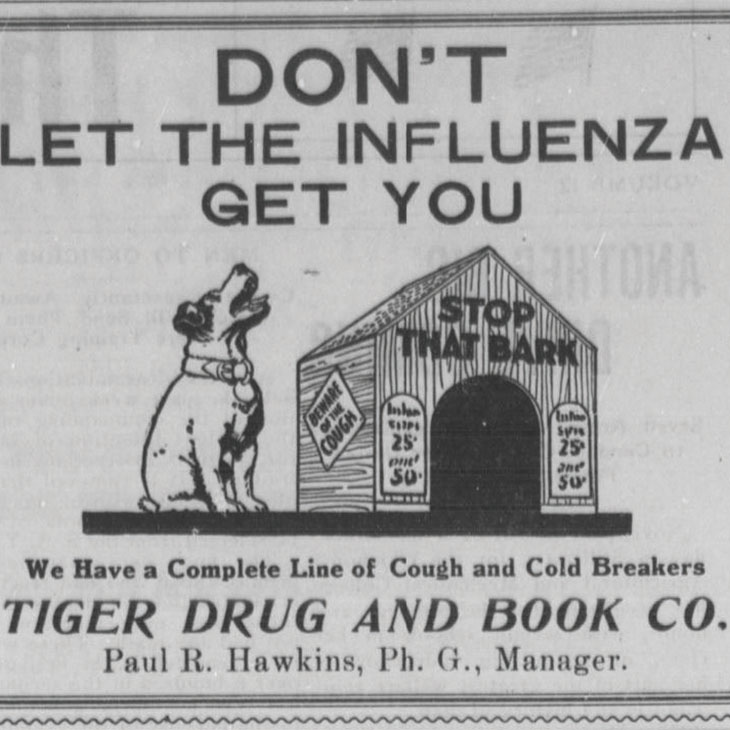

At this same time, the U.S. government and American Red Cross began promoting precautions. All were encouraged to avoid crowds, sneeze or cough into a handkerchief, wash hands regularly, use antiseptic sprays, get plenty of fresh air, drink sufficient amounts of water and eliminate useless handshaking. Recommendations also included no sharing of cups, towels or eating utensils.

The student newspaper published numerous updates on the influenza status of many students, faculty and staff and posted notes for organizations “hit by the flu,” such as the college band and Advanced Dictation Club. Announcements included the cancellations of events such as public lecture courses and notified students and team members that football practice was continuing in spite of many players being ill.

Dr. John Duke, the state health commissioner, declared a statewide quarantine on Oct. 18. All public gatherings of more than 12 people were banned, but Oklahomans could still eat out and classes continued on campus.

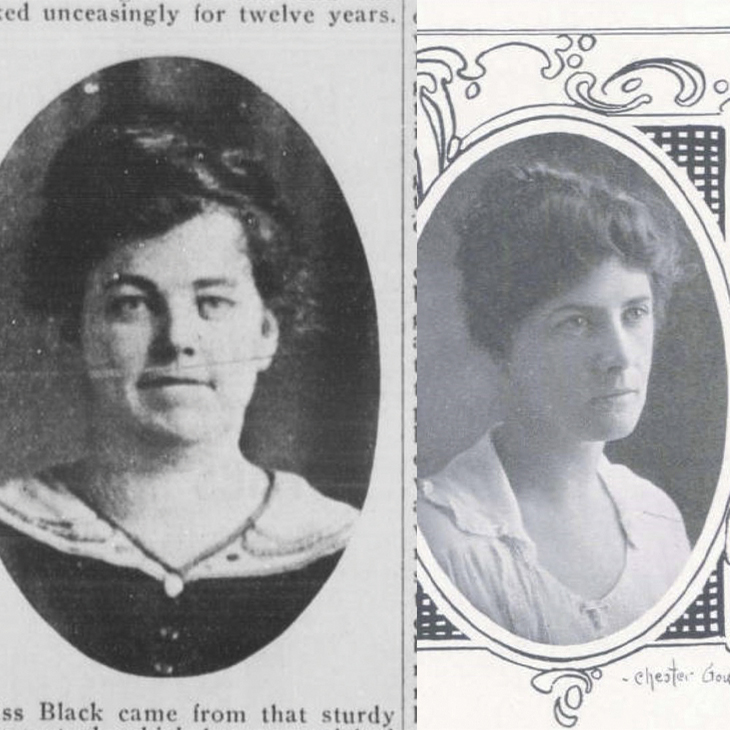

On Oct. 19, the college paper reported the death of James Alva Conner, the first SATC student to die of the Spanish flu, three days earlier. One week later, the death of Ora Ardell Black was announced. She was an English teaching assistant in the OAMC secondary school. When the outbreak hit in September, she volunteered as a nurse until overcome by the disease herself.

More residents were infected and more deaths reported in Stillwater and elsewhere in the state. In the midst of this suffering, some students were upset that they couldn’t hold a pep rally for the football team. The Oklahoma Health Administration allowed classes but wouldn’t approve a pep assembly and discouraged cheering at the Nov. 2 football game, thinking that yelling and cheering would lead to throat irritation and increase susceptibility to influenza.

Organized cheers for the game would be eliminated.

The college had been proud to announce that it was the only higher education institution in the state that remained opened during the influenza pandemic. SATC persisted with drills and classes continued. Eventually, 200 SATC members were afflicted and the college received word that six former students died of the flu while serving in the military, both at home and abroad.

The Red Cross provided six nurses and a temporary guard around the college “hospital” controlled the number of visitors. As new cases fell, social activities expanded. An interfraternity dance took place Nov. 9, and Stillwater churches conducted worship services beginning Nov. 10. Scattered influenza news items continued to appear in local newspapers for another year as the third wave of the pandemic didn’t end until December 1920, but the worst was over in Stillwater by mid-November 1918.

Ultimately, 500 OAMC students and SATC cadets, roughly 30 percent of the student body, suffered influenza symptoms. College employees and their families experienced the same rates of infection, and the college suffered two deaths, one student and one employee. There were additional deaths in Stillwater and surrounding communities.

Ten years later, a campus hospital was built to meet the medical needs of students, in part a response to the challenges faced during the influenza pandemic of 1918.

On a larger note, leaders in the United States and European countries engaged in World War I knew about the expanding influenza outbreak beginning in early 1918, but censored stories about the epidemic fearful that publication would damage morale. Some blamed the Germans, but those soldiers suffered at the same rates as the French, English and Americans. Spain was not involved in the war, and the influenza outbreak received wide coverage in that country.

That coverage led many to assume it must have started in Spain, so they christened it the Spanish flu. The original source of influenza remains unconfirmed; it may have started in Kansas according to many scholars.