Cowboy Chronicles: Student life in the Roaring '20s had a very different look

Thursday, December 17, 2020

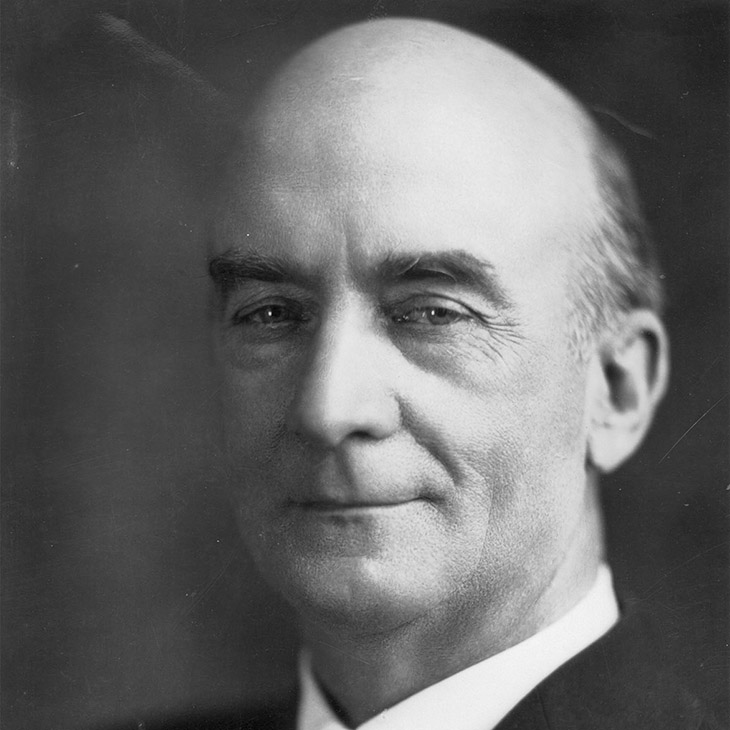

Life at what’s now Oklahoma State University was considerably different 100 years ago. Oklahoma A&M College’s fourth president in four months, Bradford Knapp, arrived in Stillwater on Sept. 17, 1923, taking control of an anxious and nervous institution yearning for stability. Leaders in the Oklahoma State Board of Agriculture assured Knapp that he had their complete support and cooperation.

Many of the faculty had resigned or been fired during the summer of 1923, but Knapp was able to persuade some to return and recruited others as replacements. With strong student enrollments and a stable budget, Knapp initiated a new era of enthusiasm at the land-grant college. The students affectionately called him “Prexy,” and he actively participated in many of their academic and social activities.

However, the Roaring ’20s brought societal changes to colleges and communities across the country. Exposed to the worst horrors of human conflict, large numbers of young Oklahoma soldiers had traveled extensively during World War I, experiencing exotic cultures and glamorous locations, altering expectations of college life when they returned home. Women could vote, movies added sound, jazz became popular and college dances became more popular. Automobiles became more affordable, making students more mobile. Ford Motor Co. produced half a million cars in 1919 that sold for about $500 each; five years later, it produced 2 million that sold on average for $265.

Since the inception of the college, various edicts had been issued in attempts to modify student conduct. One of Knapp’s first objectives was to organize all student rules and regulations. Within three months of his arrival, he published a comprehensive list of 104 rules to guide and direct student behavior. The regulations applied to all current and prospective students. These expectations also came with varying degrees of consequences if violated, from demerits to expulsion.

Knapp required all faculty to assist him in these efforts “to correct any misconduct of students, or report violations” to him or the Committee on College Government. He created this committee “to investigate infractions of college regulations by students, to ascertain the facts concerning violations of the rules, and to recommend to the president proper and suitable discipline in each case.” The College Government Committee “shall have the power to require any student or employee of the college to appear before them on due notice, and to answer truthfully such questions of fact material to the case as the witness may be able to answer out of his own knowledge.”

Some of the 104 rules and regulations were to be expected. For example, the use of tobacco in all forms, gambling and liquor were all banned (the last two items outlawed under state and federal laws). Restrictions limited when certain activities could take place and where students must be at specific times. Students were required to be at their residences for a 7:30 p.m. curfew Monday through Thursday. These evenings were considered “closed.” Friday through Sunday evenings were defined as “open,” and students could stay out until 10:30 p.m. If they did not live in campus residence halls, they could only reside in approved boarding houses, Greek housing or the family home, and the individuals responsible for those housing options had to see that all rules were followed. The Committee on Boarding and Rooming Houses reviewed all applications to provide boarding options in Stillwater.

There were exceptions to the evening curfews, but only for students attending pre-approved events and parties. Chaperones were required at all events women attended. At least two of the mandated chaperones were to be married faculty members if the activity was a party. The organization sponsoring the event was required to submit a written application to the Committee on Plays and Social Entertainment at least one week prior to an activity, requesting approval. These applications included the place, date and time of the function, names of the chaperones, and the number of guests attending.

The Committee on Social Entertainment and Student Plays also served as censors for all entertainment, exhibitions and plays on campus or in the community. The student organization sponsoring the activity was required to submit details of the entire program to ensure that these events were “in good taste, clean, moral and commendable.”

Other rules seem a bit obscure, such as students could not leave Stillwater without permission from their academic dean, women needed consent from the dean of women before changing boarding houses, and graduating students were required to attend commencement to pick up their diplomas. Knapp was the only person who could provide exemptions to this last rule.

While there were many minor challenges to some of the 104 rules and regulations, the one that caused the most headaches for the president was Rule No. 11: Students must not use motor vehicles for social purposes. Students who use automobiles for legitimate business purposes, for transportation to and from their homes and for other purposes not classed as “social” shall file the state license number of their cars in the president’s office.

Immediately preceding Knapp’s arrival, the Board of Agriculture, serving as regents for the college, outlawed the use of student-owned or operated automobiles on the A&M campus. The prevailing opinion of the time was that cars were a potential deterrent to good scholarship and increased immorality on campuses. This was not a problem just in Stillwater. Knapp corresponded with administrators at other campuses, and OAMC was not the only college with rigid automobile use restrictions. When writing to an administrator at another college Knapp stated: “… prevention of immorality so prevalent over the entire country, due largely to the indiscriminate use of automobiles by the young” was the primary reason for the car ban. He then added, “… it is a noteworthy and important fact that students in institutions everywhere in the country who have their own automobiles are generally failures in their college work. The use of automobiles at the college invite failure and is a waste of the student’s time as well as a financial obligation to the parents.”

The OAMC president’s argument yielded mixed results. For the one-year period beginning in April 1924 three male students were expelled and five students suspended for “joy-riding” or the social use of an automobile. Two of the expelled students had liquor in the car with them, doubling the likelihood for expulsion. An additional 25 students were placed on social probation for joyriding. Stillwater entrepreneurs that offered car leases by the hour or day made enforcement more difficult.

Knapp had found this student regulation virtually impossible to enforce with only faculty observers and Stillwater police to assist him. During the fall of 1925, Knapp appealed to such Stillwater civic groups as Rotary and Lions clubs. He requested their assistance in the enforcement of the joy-riding prohibition around the community, wanting local residents to contact him and other campus authorities regarding observed infractions. Knapp and his agents also visited with Stillwater families, campus groups and those living in Greek housing.

By the spring of 1926, there were 99 student-registered automobile permits with a campus enrollment of 2,900. Less than 3.5 percent of the student body had registered vehicles. Violations were few. The only continuing area of concern involved using taxis during inclement weather. Knapp felt that some students were defining “inclement” much more broadly and taking advantage of this exception in use. He later tightened this loophole.

All parents received letters regarding the policy. Students whose parents did not reside in Stillwater received one letter that included the total ban on their children having cars. A different letter went to Stillwater parents since their children could have very limited use of automobiles with a registered permit. To receive a permit, a Stillwater student needed approvals from the dean of their academic unit, the chairman of the Committee on College Government and the college president. Permits were granted only if all three were “convinced that it is necessary for the student to have use of an automobile.” If approved, four copies were made, one for each permit grantor and one for the student to carry in the vehicle.

At this time, there were no parking lots on campus, and parking permits were not required. Very few faculty and staff drove to campus because most lived in neighborhoods east and south of the college. The main avenue at the college was a one-way street with parking permitted on one side. Knapp may have been the only employee with a reserved parking spot for his car, which was stored at his home on campus. With limited student demand, parking on campus was not a problem, one of the few benefits associated with this rule for the entire college community.

Eventually the automobile restrictions changed and a growing number of students owned cars. Modifications of other rules occurred over the decades, but university leaders continued to recommend appropriate guidelines within the campus community to support academic achievement and ensure the health and wellbeing of those who worked and studied at the college.