Cowboy Legends: Commemorating the trailblazers of OSU Veterinary Medicine

Thursday, November 20, 2025

Media Contact: Kinsey Reed | Communications Coordinator | 405-744-6740 | cvmcommunications@okstate.edu

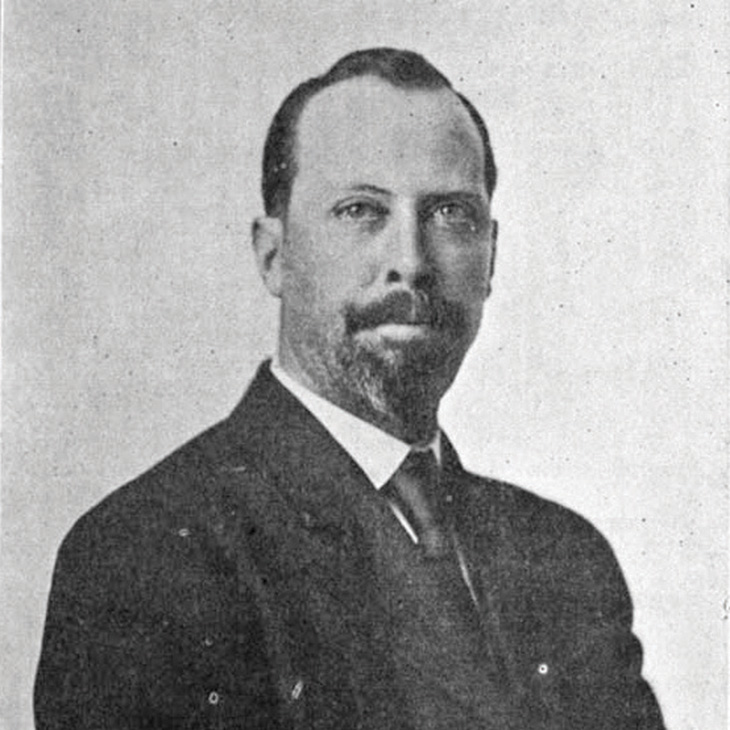

Dr. Lowery L. Lewis

In the summer of 1896, a pioneering spirit arrived at then Oklahoma A&M College.

Dr. Lowery Layman Lewis, a Tennessee-born veterinarian with a sharp mind and a heart for animals, was appointed professor of veterinary science. What followed was a legacy that would shape the future of veterinary medicine in Oklahoma.

Lewis didn’t just teach — he built. In the early days, his classroom was a whirlwind of subjects: physiology, zoology, comparative anatomy, materia medica and veterinary medicine. His lectures tackled the science of disease and the power of prevention, introducing students to the role of bacteria and the importance of disinfectants. But his vision extended far beyond the lecture hall.

As the territorial veterinarian, Lewis immersed himself in the challenges of the Southwest. He investigated deadly diseases like glanders and anthrax, and his research connected him with regional livestock producers. In 1899, he expanded his role, diving into the bacteriology of milk and the study of horse diseases — fields previously untouched in Oklahoma.

By 1901, Lewis had moved into the new library building, later known as Williams Hall, where he continued groundbreaking work on parasites and the toxic effects of the loco plant. His efforts weren’t just academic. In 1902, he distributed over 123,000 doses of blackleg vaccine to more than 1,500 cattle owners, saving countless animals and livelihoods.

Lewis was a man of action during a time of transformation. The Meat Inspection Act of 1906, spurred by public outrage over unsafe meat processing, created a surge in demand for trained veterinarians. Lewis responded by helping establish a School of Veterinary Medicine at OAMC in 1912. He served as dean of the School of Veterinary Medicine and the School of Science and Literature, crafting a curriculum that balanced general education with specialized veterinary training.

Despite financial and political hurdles — including a devastating fire in Morrill Hall and legislative deadlocks — Lewis remained steadfast. His research on hog cholera and blackleg continued to protect Oklahoma’s livestock industry, and his advocacy helped secure funding for serum distribution and agricultural extension services.

Born in 1869 and educated at Texas A&M and Iowa State University, Lewis brought technical expertise and a charismatic presence to Stillwater. He married Georgina Holt and raised two children, Samuel Lee and Ruth. At the time of his death at age 53 in 1922, he held multiple titles: professor, researcher, dean and even acting college president.

His influence extended beyond academics. A passionate supporter of athletics, Lewis took the initiative to organize early track and football teams, encouraging students to sample different events and participate for their school. To students, he was known affectionately as “Old Doc Lew.”

Lewis helped locate the football field, placing it north of Morrill Hall. In 1910, the Athletic Association heartily endorsed the suggestion to honor Lewis by naming the athletic grounds Lewis Field. The new name was made official during the 1913-14 academic year.

Dr. Clarence H. McElroy

Before he was “Dean Mac” and helped launch Oklahoma’s first veterinary school, Clarence Hamilton McElroy was a young boy from Tulsa with grit in his soul and a dream in his heart.

McElroy’s journey began humbly — working as a janitor in Old Central for 10 cents an hour and sleeping in the attic to afford his education. “My board and room cost $2.50 a week. One year, I spent only $90,” he recalled. That tenacity would define his legacy.

After earning his bachelor’s degree in general science in 1906, McElroy returned to OAMC in 1909 to assist the legendary Dr. L.L. Lewis. Inspired by Lewis, McElroy pursued veterinary medicine at St. Joseph Veterinary College in Missouri, earning his DVM in 1919. He returned to Stillwater and quickly became a cornerstone of the veterinary program.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, McElroy wore many hats — assistant professor, dean of the School of Science and Literature, chairman of the Biological Sciences Group, and, like Lewis, even acting president of the college. He was also dean of men, a role he affectionately called “Dean of Wild Life,” and served on the Athletic Cabinet.

But McElroy’s most enduring contribution came after World War II. With the livestock industry booming and demand for veterinarians rising, McElroy and college president Dr. Henry G. Bennett championed the creation of a new School of Veterinary Medicine. Their efforts culminated in the school’s historic opening on March 1, 1948, with McElroy acting dean.

The launch was anything but glamorous. Classes were held in a repurposed World War II army hut, and supplies were scarce. McElroy scrambled to secure dissecting tables, microscopes and barrels of formaldehyde. He personally recruited students; many of whom had helped prepare bones for anatomy labs in a prefabricated hut. When the school opened, he greeted them, knowing each by name.

He oversaw the development of a four-year professional curriculum. Despite limited resources, the school thrived thanks to the dedication of faculty and students. Surgical demonstrations were even broadcast via closed-circuit television — a pioneering move in veterinary education.

McElroy retired in 1953, leaving a legacy of resilience, innovation and mentorship. In 1954, the Dean Clarence H. McElroy Award was established to honor the outstanding senior student each year — a testament to the values he embodied: scholarship, character and professional excellence.

“Dean Mac” passed away on March 7, 1970, at age 83, but his spirit lives on in every student who attends OSU’s veterinary school building, now known as McElroy Hall.

Dr. Harry W. Orr

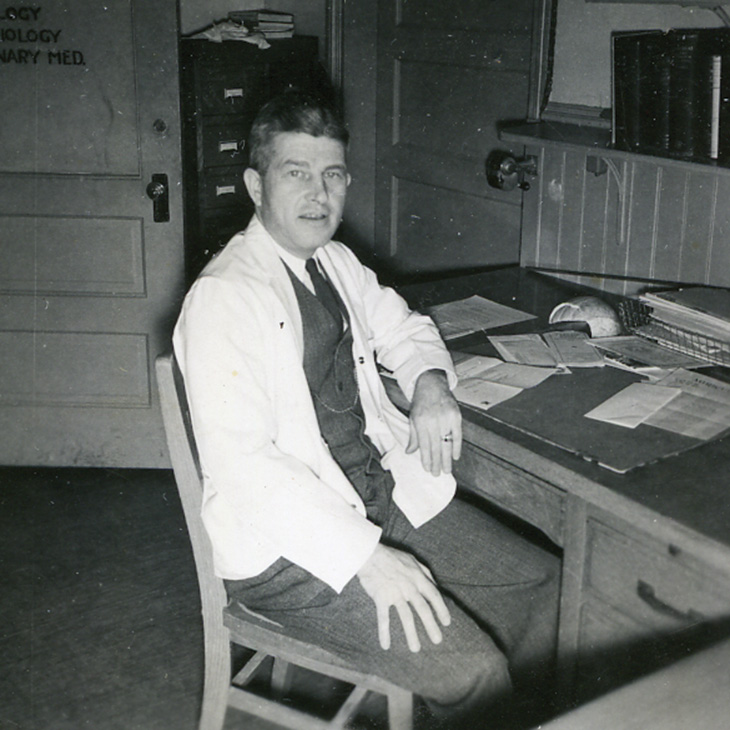

When Dr. Harry William Orr stepped into the role of dean of the School of Veterinary Medicine at Oklahoma A&M College on July 1, 1953, he inherited more than a title — he inherited a school in crisis.

The facilities were inadequate, morale was low, and accreditation was hanging by a thread. But Orr, a seasoned educator and tireless advocate, brought with him nearly four decades of experience and a deep understanding of the institution’s needs.

Born in Mystic, Iowa, on Aug. 9, 1896, Orr earned his DVM from Iowa State University in 1918 and served as a second lieutenant in World War I. He joined OAMC in 1919 as an assistant professor in the original School of Veterinary Medicine under Dr. L.L. Lewis. When the school was dissolved in the 1920s, Orr remained, teaching physiology, human anatomy and animal disease courses to pre-medical and agriculture students. He earned his master’s degree in 1930 and became head of the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology in 1948.

Orr’s leadership was marked by relentless advocacy. He pushed for separate budget allocations to protect the veterinary school’s funding and worked with state legislators to secure appropriations. His efforts bore fruit in 1955 when Oklahoma voters approved $15 million in bonds, with $3.475 million allocated to OAMC for capital improvements — including a new unit for the veterinary medicine building.

Despite suffering a heart attack in 1954, Orr continued to work from home, urging state officials to recognize the school’s potential. “The School of Veterinary Medicine could contribute a great deal more to the welfare of all Oklahomans if it were supplied with adequate facilities,” he wrote. His passion and persistence helped stabilize the school during a precarious time.

Orr passed away suddenly on Jan. 14, 1956, at 59. Though his tenure as dean lasted only 30 months, his influence spanned nearly four decades. His colleague, Dr. A. E. Darlow, described him as “a scholar, an administrator, and a man whose legacy endowed the college with a rich inheritance.”

In 1958, the Dean Harry W. Orr Award was established to honor third-year veterinary students who demonstrate exceptional academic achievement and professional growth. It remains a tribute to a man who helped guide the school through one of its most difficult chapters and laid the groundwork for its future success.

Dr. June D. Iben

In 1955, a quiet revolution took place at OAMC.

Among the graduating class of the College of Veterinary Medicine stood a woman who had defied convention, challenged expectations and made history. Her name was Dr. June Iben, and she was the first woman to earn a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree from the institution.

Born in Monaca, Pennsylvania, in 1927, Iben’s path to veterinary medicine was anything but straightforward. Her father forbade her from pursuing the field, so she began her academic journey as a chemistry major at Allegheny College. But her passion for animals couldn’t be silenced. After working for a small animal practitioner and researching blood grouping in horses, she overcame familial opposition and applied to veterinary schools — only to face another barrier: gender bias. One school told her they only accepted women in pairs.

Undeterred, Iben applied to OAMC. The day her acceptance letter arrived, she was so overwhelmed with joy that she had her friends read it aloud repeatedly to confirm it was real. At school, she faced skepticism from some classmates and faculty, but she met it with humor, resilience and hard work. “I was not only a woman but a damn Yankee to boot!” she joked, crediting fellow Northerner John King for helping break the ice.

Iben’s class, the Class of 1955, was full of firsts. They were the first to wear proper DVM gowns with gray paneling and the first to have a uniform class photo.

After graduation, Iben joined the teaching and research staff at Washington State University, worked in private practice, and eventually opened her own clinic, which she ran for 35 years. But her true calling was with large exotic cats. She hand-raised lions, bobcats, a margay, a cougar and countless large-breed dogs. Her home was shared with “CC” (short for “common cat”) and later, a rescued cougar named Munchkin. She once said her dream was “to go to sleep at night listening to the purring of a cougar and the roar of lions”— a dream she fulfilled at the Western PA National Wild Animal Orphanage.

Her work with exotic felids earned her national recognition. She studied in Africa with George and Joy Adamson of “Born Free” fame. She was featured in the first edition of “Who’s Who in American Women” and received the Public Service Award of Merit from the Pennsylvania Veterinary Medical Association in 1999. She was also inducted into Monaca’s Community Hall of Fame and cited in multiple veterinary history publications.

She passed away in 2008 at 81, leaving a legacy of courage, compassion and trailblazing achievement. Her story is a testament to the power of perseverance and the impact of one woman’s determination to follow her calling — no matter the odds.

Photo By: OSU Archives

Story By: Jordan Bishop | Vet Cetera Magazine