History professor’s new book explores Fort Worth Narcotic Farm, decades of addiction treatment in U.S.

Thursday, December 5, 2024

Media Contact: Elizabeth Gosney | CAS Marketing and Communications Manager | 405-744-7497 | egosney@okstate.edu

Before coming to Oklahoma State University in 2016, Dr. Holly Karibo worked at a university near Fort Worth, Texas, where a cluster of old 1930s-era buildings caught her eye.

Sitting on the Texas prairie, these were the remains of the historic Fort Worth Narcotic Farm, which is the subject of Karibo’s third book, “Rehab on the Range: A History of Addiction and Incarceration in the American West.”

An OSU associate professor of American history, Karibo was drawn to “the Farm” because of the allegedly kinder treatment model it attempted. Established through the 1929 Narcotic Farm Act, the Farm was one of two federally funded treatment centers — the other was in Lexington, Kentucky.

Once open, the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm was the only institution in the nation at the time dedicated to treating drug users who lived west of the Mississippi. For over 30 years, the narcotic farms saw more than 60,000 patients, many of them from Oklahoma.

The regional aspect resonated with Karibo, especially given contemporary debate about the opioid crisis and state legal efforts to bring drug companies to justice for their part in the epidemic. In a 2019 piece for CNN, Karibo wrote that Oklahoma’s successful case against Johnson & Johnson fueled national calls to hold private companies liable for the damage their practices caused. Johnson & Johnson was eventually ordered to pay Oklahoma $572 million to help the state fund abatement programs.

That novel legal strategy reminded Karibo of earlier abatement attempts within the Southern Plains and American Southwest. As initially designed, the narcotic farm model was meant to blend modern psychiatric treatment, physical rehabilitation and vocational therapy. It did in fact have a working farm, as many believed that hard work and clean living in a rural community would play an important role in moral uplift of the patients.

But Karibo soon found a much more complex picture: the Farm was also prison-like. Laws in place since 1914 had made it a crime to use drugs. Penologists — specialists in prison management and the treatment of offenders — were on the rehabilitation team at Fort Worth. In fact, many patients at the Farm were actually sentenced there.

In her research, Karibo found William Hancock, whose first arrest in Oklahoma City was followed by 25 arrests on various charges, including illegal drug use. This eventually forced him to the Farm, where he was among other Oklahomans who hailed from rural farming communities and oil boomtowns alike. But what these men encountered didn’t often match what they were promised.

“The Farm presented as a place based on therapeutic care models,” Karibo said. “But in many respects, it contributed to the country’s tilt toward criminalizing drug use.”

Dr. Brian Hosmer, head of the OSU Department of History, said Karibo’s work gives important historical context amidst shifting opinions on drug-related charges.

“In 2016, Oklahomans voted overwhelmingly to reclassify simple drug possession from a felony to a misdemeanor,” Hosmer says. “People here are supportive of new models and want a humane approach. Holly’s work helps us see that it’s a full circle. The therapeutic options on the table today have important precedents, and they’re in our backyard. But she also helps us see it’s not easy to get right.”

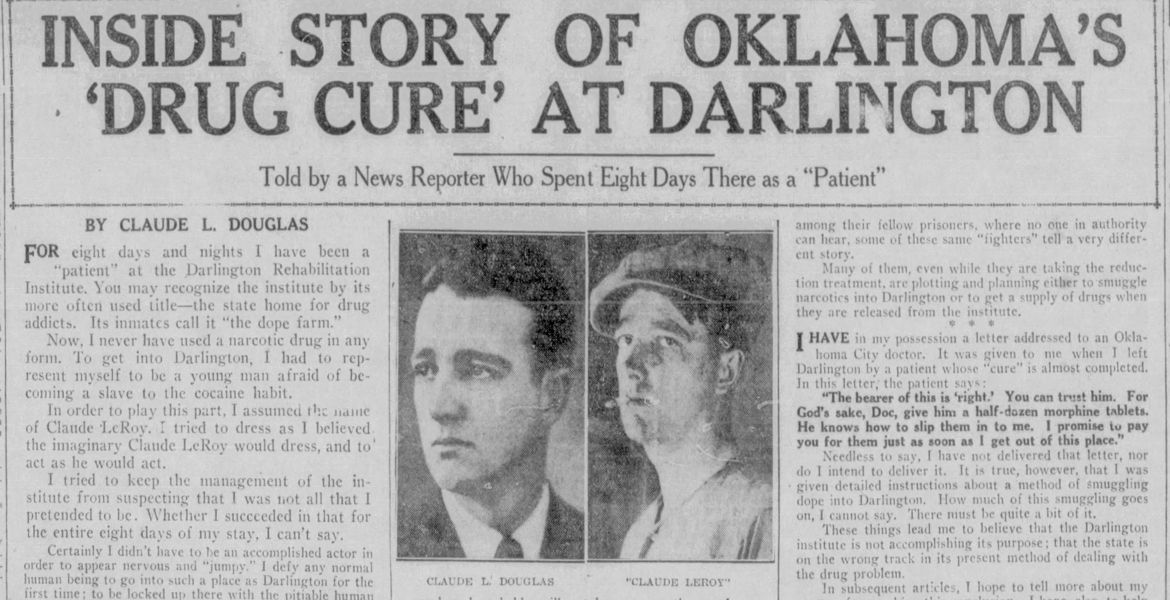

For Karibo, it’s about understanding what went wrong. In her research, she uncovered a little-know attempt by the state of Oklahoma in the 1920s to provide state-funded addiction care. The Darlington Institute, as it was known, was only in operation for a short time due to political infighting, lack of funds and accusations of abuse at the hands of institute officials.

“Drug cultures are spatial as much as they are sociological,” Karibo said, describing Texas and Oklahoma as a specific subzone in the 1920s to the 1960s when drug markets, labor and politics shaped drug subcultures and drug policies.

“Today we think of states like these as epicenters of the carceral state, with drug use a big reason why the prisons are full,” Karibo said. “It wasn’t necessarily like that when my study starts, and it’s important to remember those possibilities. But we also need to know how a therapeutic model can become carceral. It’s good to be vigilant.”

“Rehab on the Range: A History of Addiction and Incarceration in the American West” was released on November 19 from University of Texas Press as part of its American Studies Series. For more information, contact Dr. Holly Karibo at hkaribo@okstate.edu.

Story By: Department of History Staff | history@okstate.edu