Geography, plant biology professors secure NASA funding for grasslands research using remote sensing

Thursday, April 10, 2025

Media Contact: Elizabeth Gosney | CAS Marketing and Communications Manager | 405-744-7497 | egosney@okstate.edu

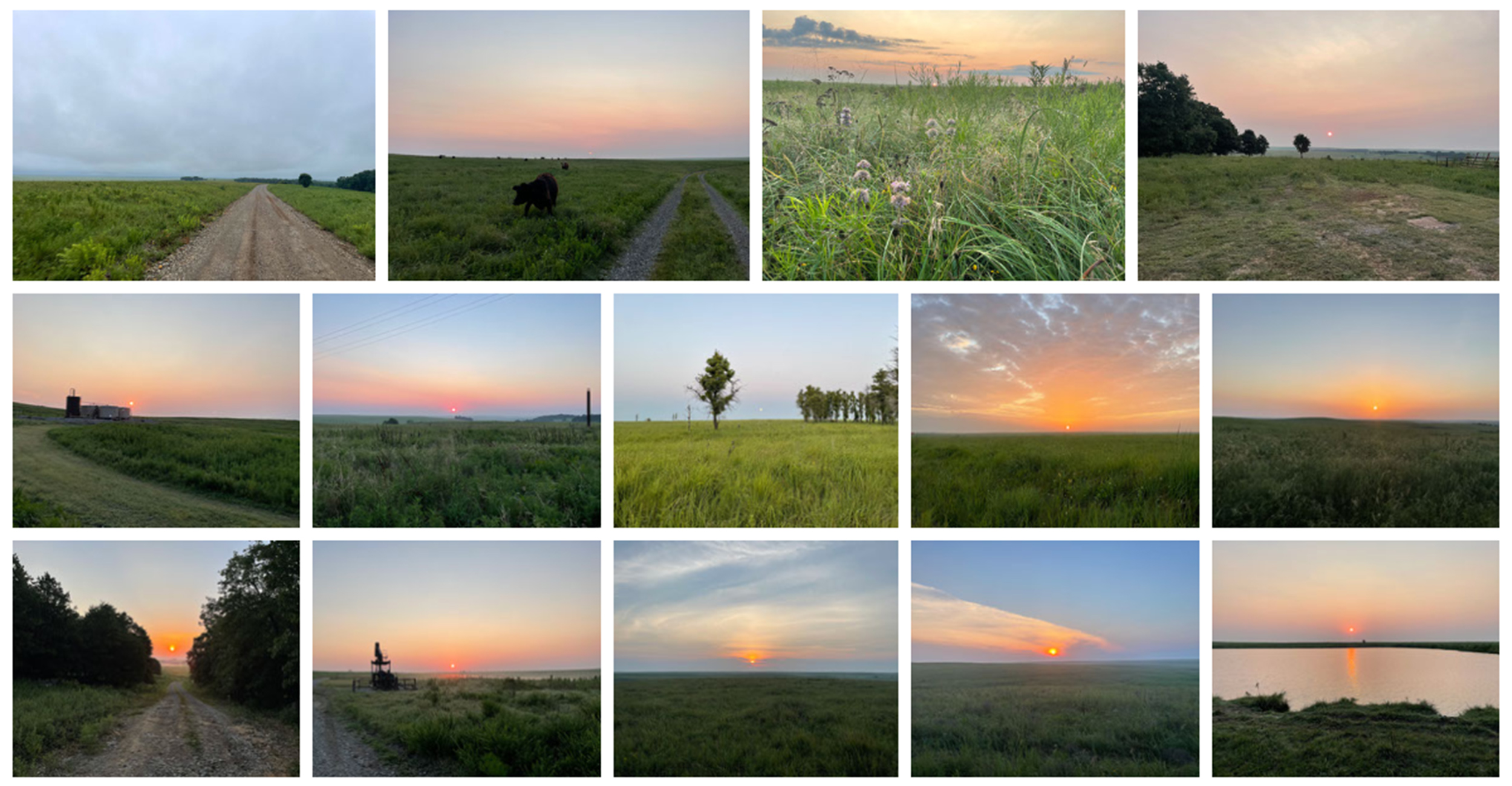

A team of researchers led by Oklahoma State University Department of Geography’s Dr. Hamed Gholizadeh recently received more than $730,000 in NASA funding to further its research into grassland systems, specifically looking at how management practices like prescribed fire and grazing are impacting biodiversity.

The project, titled “HI-GRASS: Holistic Investigation of Grassland Systems across Scales,” will use a novel integration of remote sensing technology called hyperspectral remote sensing — as well as movement ecology, landscape ecology, metagenomics and microbial ecology — to understand how and why grassland biodiversity is changing.

“To be more specific, we will collect remote sensing data from satellites, airplanes and OSU’s cutting-edge ALEOS drone, and then use field-based observations to develop and validate our models,” Gholizadeh said. “We will then apply these models to remote sensing data to gain a better understanding of biodiversity across large, contiguous areas.”

While Gholizadeh received his first NASA funding for grassland research in 2021, the HI-GRASS project is incorporating new research elements with the help of co-PIs Dr. Benedicte Bachelot of OSU’s Department of Plant Biology, Ecology, and Evolution and Drs. Ran Wang, Nicholas McMillan and John Gamon of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

“In this project, we have added new components such as animal movement and soil microbial ecology to our efforts,” Gholizadeh said. “[We’re] aiming to understand how grazing animals, particularly cattle, affect or respond to grassland biodiversity.”

For Bachelot, collaborating with Gholizadeh and their colleagues at Nebraska has allowed her to ask research questions from new angles; specifically, a wide angle.

“My work is typically down at a relatively small scale, relying on a lot of data collection in the field,” Bachelot said. “Collaboration with Hamed has enabled us to think about larger scales and whether or not hyperspectral imagery can detect changes in belowground communities. Now, collaborating with the University of Nebraska brings another fascinating aspect to the story about animal movements.

“This type of collaborative effort really pushes you outside of your comfort zone, but it makes your research program so much more diverse.”

Wang, who is an assistant professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, echoed Bachelot’s sentiments about the benefits of having a team with varied fields of expertise.

“Discovery often happens when new people bring in new ideas to solve old problems,” Wang said. “The interdisciplinary team with people from different locations — when it works well — cultivates this by embracing open mindedness and, to some extent, eliminating bigotry.”

Quoting Mark Twain, Wang added, “‘Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.’ This applies to research as well.”

Gholizadeh further explained that working with researchers in other fields wasn’t just a luxury, but an absolute necessity.

“This transdisciplinary approach allows us to put GPS trackers on cattle to track

their movements, or investigate soil fungal and microbial communities to understand

their impact on grassland biodiversity, and scale up these insights to the entire

landscape using remote sensing,” Gholizadeh said. “To make this even more interesting,

we will be conducting all these experiments in two different grasslands: the Tallgrass

Prairie Preserve in Oklahoma and the mixed-grass prairies of Nebraska Sandhills.”

Looking forward, Gholizadeh has a clear view of what the potential implications are

of his team’s research — from the preservation of ecosystems to workforce development.

“Grasslands are among the most under-studied, under-valued and threatened ecosystems,” Gholizadeh said. “Their transformation into other land-cover types, along with widespread degradation, has led to significant biodiversity loss ... pushing grasslands closer to a tipping point where restoration becomes increasingly difficult. By developing a biodiversity monitoring system, our research will help assess the health of grasslands and inform better conservation strategies.

“Additionally ... graduate and undergraduate students will be deeply involved, gaining hands-on experience in cutting-edge topics such as remote sensing, animal movement tracking, and metagenomics. This training will equip the next generation of scientists with the skills needed for future research and conservation efforts.”

Gholizadeh pointed out that the support of his department and the College of Arts and Sciences has aided the success of research — research that is just one of many ways geography is helping improve the world.

“Geography is a diverse field, encompassing topics from cultural and socioeconomic studies to environmental science, climate research, and technological applications like remote sensing,” Gholizadeh said. “This breadth of expertise fosters an environment where projects like HI-GRASS can thrive.”