Movement in Aging

Tuesday, February 9, 2016

This story appears in the 2016 issue of Vanguard, Oklahoma State University’s Research magazine.

As humans age, our motor function decreases, leading to a higher risk of falls and injuries, which can have devastating results. An ongoing study led by Oklahoma State University exercise physiology assistant professor Jason DeFreitas is researching what physiological changes cause the decline of motor function in aging.

DeFreitas noted strong evidence in recent studies that suggests muscle spindles, sensory receptors found in vertebrate muscles, have a more direct role in motor function than previously believed. He designed a study to specifically test if losses in muscle spindle function are responsible for, or at least play a significant role in, age-related losses in motor function.

The study challenges existing paradigms about motor control, hypothesizing that age-related sensory losses precede motor losses and may actually cause them.

“We think that spindles may have a significant influence on motor control during every movement. However, this isn’t what is currently being taught,” DeFreitas says.

DeFreitas joined Oklahoma State University in 2013 and brought with him an expertise

in neuromuscular physiology and a passion for research.

“This is my first aging study. I’m taking my background in the neural control of movement, the spinal cord, and the neuromuscular system and applying it to the aging population,” he says. “I like solving puzzles, especially those that require creative solutions, (much like) designing a research study to answer the unknown.”

In 2014, DeFreitas received funding from the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (OCAST). Research funded by OCAST investigates causes, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of human diseases and disabilities and facilitates the development of innovative health care products and services. The funds, renewable for up to three years, have supported the initial phases of DeFreitas’ study, allowing him to purchase new equipment and hire research assistants.

DeFreitas and his team test subjects ranging in age from 18 to 98 years old. To date, more than 100 subjects have been tested.

“We have tested a lot of healthy, college-age individuals, as well as older subjects who have severe motor and sensory deficits (over the age of 75). We’re working to add more subjects in the 30- to 60-year-old range to better define the aging process.”

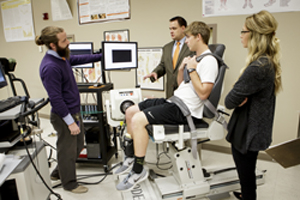

If they are able, participants visit the Applied Musculoskeletal and Human Physiology Laboratory on the Stillwater campus. The lab is one of only six in the United States and 25 worldwide equipped with the most recent advancement in motor unit technology, called surface dEMG. The system uses a non-invasive surface sensor to detect and measure the neural activity during voluntary movements.

“The brain controls muscles through the use of neurons, and this state-of-the-art system allows us to non-invasively detect the activity and behavior of those neurons,” DeFreitas explains.

During a lab visit, subjects’ balance is evaluated using a Biodex Balance System. Static measures, such as how much a person sways while standing, and dynamic measures, such as the ability to adjust to movements, are recorded.

“Balance requires a unique integration of both our sensory and motor systems. These

assessments allow us to determine which of these systems, if any, has a deficit that

could affect balance and fall risk,” DeFreitas says.

If older individuals are unable to go into the lab, a mobile version of the tests can be performed. DeFreitas and his team have recruited study participants at the Stillwater Senior Center and visited assisted living centers and nursing homes in the area with their mobile testing center.

Why it matters

DeFreitas’ study is in the second phase of a five-phase plan. In the coming year, he is working on a proposal seeking funds from the National Institutes of Health that would support his work as it enters phase three.

If, as DeFreitas hypothesizes, a strong relation-ship can be found between losses in muscle spindles and age-related motor losses, the next step is a long-term longitudinal study that will solidify the cause and effect relationship. Ultimately, DeFreitas would like to design training interventions and do outreach to educate retirement communities about what can be done to delay age-related losses in motor control.

While research is DeFreitas’ passion, he genuinely enjoys mentoring graduate students. His efforts in working with OSU graduate students were recognized in 2015 when he was named the Phoenix Faculty Award winner. The award is student-nominated and presented by the OSU Graduate and Professional Student Government Association.

DeFreitas spends time with his doctoral students daily, including frequent brainstorming meetings. He involves them with manuscript peer-reviews, study design, grant writing and more.

“I want to give my doctoral students experience that will help prepare them to be successful faculty members in the future. I learn from them as much as they learn from me. It’s a very active relationship and we all benefit from it. The Phoenix Award was a validation for me that I’m doing things the right way and that the extra work I put in is appreciated.”