Sifting Through History

Monday, November 9, 2015

Summer is associated with vacations and family trips, a break from school and sometimes fromwork. James Cooper’s are often spent in hot attics, dark closets and musty basements.

Since 1988, Cooper, a professor of history at Oklahoma State University, has spent his summers sifting through mountains of ledgers and church records in the file cabinets and closets of New England churches to preserve a piece of history. Many of these church documents offer a rare glimpse into colonial American life.

“In essence, we are making history by preserving history,” Cooper says.

Cooper is on a records-searching team with Margaret Bendroth, the executive director of the Congregational Library in Boston. The duo approach Massachusetts churches to persuade church elders to lend records to the Congregational Library for digitization and preservation. The team hopes to expand into Connecticut and Maine in the near future.

Cooper has come away with some unexpected finds. A historian from a church in Middleborough, Mass., was at the Congregational Library to have the church’s ledgers digitized and mentioned a collection of relations the church possessed, wanting to know if Cooper would be interested in looking through them.

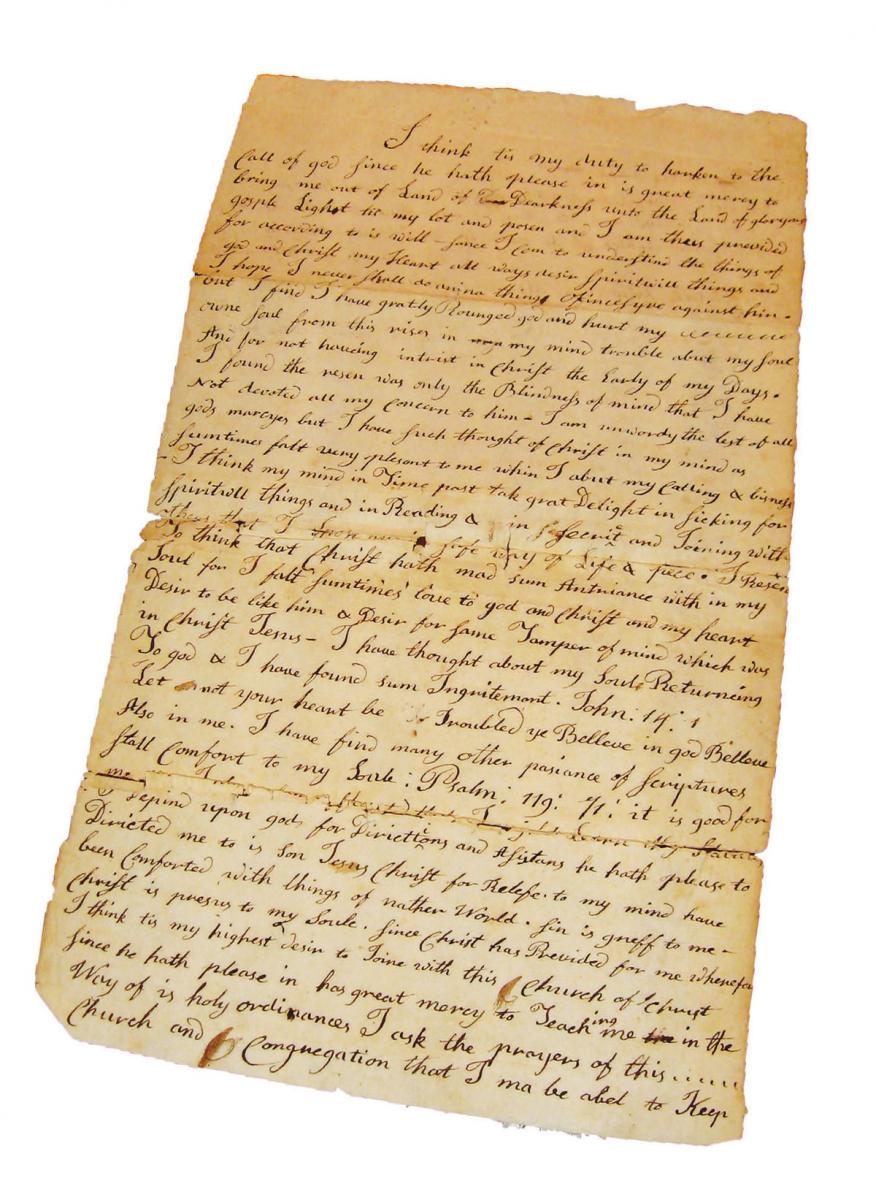

“Church ledgers, which are leather-bound books that contain birth and death records, admission records and minutes of church meetings … it is not unusual for them to survive,” Cooper says. “But loose, miscellaneous documents, like these relations, which are statements of faith that churchgoers wrote out in the process of applying for church membership, are very rare. So I said, of course, I’d love to see them.”

In that largest collection of relations to surface in New England, he found what may be the only slave relation in existence that was written in the slave’s own hand (see document above). At the time of his membership request, Cuffee (the only name we know) was the minister’s slave. In order for Cuffee to have a better understanding of his faith and read the Bible, the minister taught him how to read and write. The fact that two rare circumstances are combined into one document was an unanticipated discovery, and Cooper is extremely grateful to have played a part.

Many of these ledgers and documents have been in the New England churches for more than 300 years. Cooper says sometimes his and Bendroth’s work, while mostly dealing with parchments and papers, also requires a firm understanding of human relations. Cooper explains to the churches that their records are of significance on state and national levels as well as to the local church and community. With very few exceptions, he has found the churches in the Northeast to be cooperative and reasonable in their willingness to have their records digitized. Many members are delighted to learn the importance of their church’s early history and are happy to give the documents the proper care they deserve.

Using an inventory that was created in the 1960s, Cooper approaches the New England churches with a fairly good idea of what documents they will have in their possession.

In Rowley, Mass., a church was rumored to possess a book containing the personal writings of a minister who was known for documenting everything. Because of the minister’s meticulous record-keeping, this book is considered one of the most important documents in early American history. If two churchgoers had a dispute, the minister would invite them into his home to resolve the conflict. As soon as they left, he would record the events and discussions of the meeting as accurately as he could. He was, as Cooper says, a “virtual audio recorder.”

When Cooper arrived for his appointment at the church, the members had laid everything they had out on the table for him and gave him permission to look through the documents and see what he could take with him. The minister’s book was not there, and nobody knew where it was. The book resurfaced 17 years later after a local bank that was closing discovered an old book while clearing out its vaults. A teller remembered hearing how a local church was looking for a book that matched the description. The book was returned to the church and has since been digitized and preserved by the Congregational Library.

“I’ve been set loose in the vaults and closets of other churches, and there are just huge mounds of books and documents,” Cooper says. “I just have to commence the search, and I’ve made some amazing finds in that process.”

Many church records are lost due to fire, floods, burglary and other factors. Cooper, Bendroth and a full-time archivist at the Congregational Library work to bring in as many records as they can each summer to digitize and preserve. Currently, the digitization is being done through an outside vendor, but Cooper hopes to eventually be able to buy the equipment that will allow them to digitize records in house. This will save precious time and money.

This race against time will most likely keep Cooper busy for the rest of his life, he says, or at least until he retires. When he’s not digging through church records in New England or teaching at OSU, Cooper, an avid photographer and collector of retro video games, enjoys raising his three sons.

“I guess I was just born a collector,” Cooper says about his many hobbies and interests. “When you discover what you’re passionate about and you fill your time with those things, it’s hard to look back and not be happy you took on the challenges.”