Flight in a Sticky Situation

Wednesday, March 22, 2017

The smallest flying insects known are less than one millimeter long — and yet, they wield considerable ecological and agricultural importance. These insects serve important ecological roles such as the transmission of pollen during feeding, acting as invasive pests of agriculturally important plants and biological vectors of microbial plant pathogens. Examples of these insects include thrips, parasitoid wasps and fairy flies with wing sizes as small as a quarter of millimeter.

Since 2007, Arvind Santhanakrishnan, Ph.D., an OSU assistant professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, has been investigating the fluid dynamic limits of flapping flight at intermediate to smallest length scales. The aerodynamics of flight in these small insects remains relatively unexplored, but Santhana-krishnan and his team keep moving forward. His research helps with understanding the single insect aerodynamics that is needed for the development of mathematical models of their collective dispersal.

When the wings of small insects clap together during the flapping motion and then fling apart, there is the expectation that flight would not be efficient, but it is. This surprising fact influenced the research and has sent Santhanakrishnan and his team in a different direction.

“We can use their wing design and locomotion mechanisms to potentially design an autonomous flying or swimming vehicle that can be more highly miniaturized than what we currently have out there,” says Santhanakrishnan. Designing machinery that takes advantage of such phenomena like small robotic vehicles that move amphibiously across water-air interfaces would be a breakthrough innovation.

Santhanakrishnan and his team discovered that the wings of these small insects are basically like a thread of silk with numerous hairs. Their wings contain small bristles and very little solid membrane. Before studying tiny insects closely, he thought their flapping motion and wing design were the same as bigger insects.

“I learned the hard way,” says Santhanakrishnan. “I was confident just after getting my Ph.D. in fluid mechanics that all insects should fly in the same manner. But the tiny insects don’t.”

Santhanakrishnan started his research at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill during his postdoctoral work. He was mentored by Laura Miller, Ph.D., an associate professor at UNC in mathematics and biology who later became a collaborator on this research together with Ty Hedrick, Ph.D., an associate professor at UNC in biology.

“Dr. Santhanakrishnan is a wonderful collaborator,” says Miller. “He has incredible energy and enthusiasm for this project and everything else he works on.”

To pursue their research, Santhanakrishnan and Miller recently received a three-year collaborative grant from the National Science Foundation for $449,775.

“The research in our new NSF grant is focused specifically on understanding the flow through the bristled wings common to many tiny insects,” says Miller. Because these insects can be just a quarter of millimeters, they are very hard to see. They flap their wings like a hummingbird at 200 times a second. Collaboration with biologists is important to this research and offers an opportunity to see another perspective of this problem.

“I am an engineer. I can understand biology by reading textbooks, but certainly not to the extent of somebody that makes their living being a biologist,” says Santhanakrishnan. Studying these small insects is challenging but not impossible. By cooperating with other disciplines and universities, Santhanakrishnan’s research has a larger chance for success.

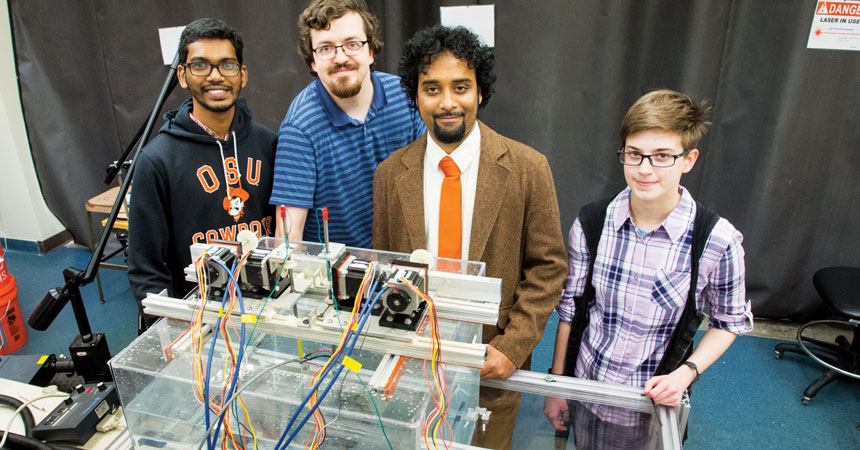

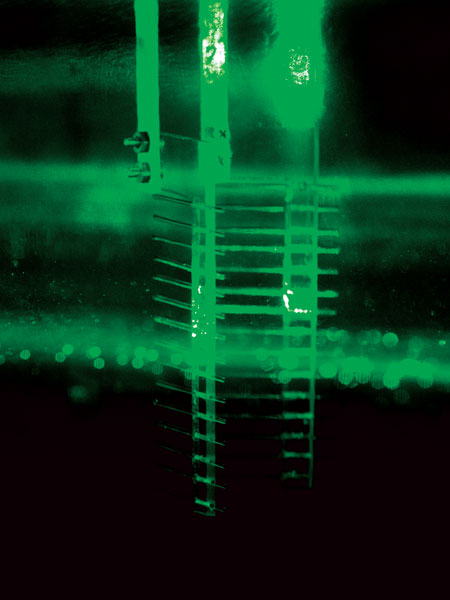

Santhanakrishnan is the director of OSU’s Applied Fluid Mechanics Laboratory, which specializes in interdisciplinary studies of locomotion, transport and pumping functions in biological systems to understand structure-function relationships. To study the flight of tiny insects, Santhanakrishnan’s lab developed a robotic platform, in which scaled-up physical models of tiny insect wings are directed to flap using several electronic motors with the same movement patterns as what is observed in the actual insects. In order to create the same frictional resistance that a tiny insect wing experiences when moving through air, the larger model wings are immersed inside a 27-gallon aquarium that is filled with sticky glycerin.

This project gives Santhanakrishnan a unique chance to train OSU students in conducting hands-on interdisciplinary research that integrates engineering and biology. Santhanakrishnan leads a team of numerous graduate, undergraduate and even high school students.

“He’s always available to discuss what’s going

on with your research,” says Chris Terrill, a graduate student in mechanical and aerospace engineering. “And he always has helpful suggestions.” He is a great role model to students by challenging himself and working on difficult problems, he adds.

“Not many people are looking at these tiny insects,” says Santhanakrishnan. “And I think it’s mainly because it’s not easy to imitate something that is so small and simultaneously complex.” He was told many times that his research topic would be difficult, but that did not change his mind.

Chosen students can travel to UNC to participate in this research in a different environment. The chance to work with a diverse group of UNC students and faculty provides opportunities to experience truly interdisciplinary research first-hand and be prepared for the future.

“The students who come here will learn how to operate high-speed camera equipment, perform stereo calibrations of multi-camera arrays and analyze the resulting video data,” says UNC’s Hedrick.

His willingness to share his experience and findings about his research helps Santhanakrishnan have an important impact on his students, who find his passion for this subject incredible. His research has a lot of potential and will impact the future of insect dispersal ecology and engineering fields.

Story by Marketa Souckova