Opening Prison Doors to Compassion

Wednesday, March 22, 2017

Many Americans see people who live on the margins of society as deserving of where they are. Not Jodi Jinks. One message that Jinks, an assistant professor of acting at Oklahoma State University, wants to get across to her students, and people in general, is the idea behind the old expression, “There by the grace of God go I.”

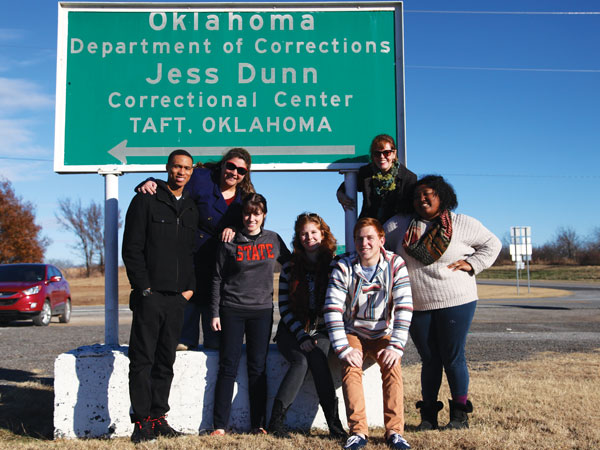

Jinks started a theater program called ArtsAloud several years ago. In 2012, as a tenure-track professor, she brought it to OSU. In the program, now called ArtsAloud-OSU, Jinks goes into prisons and works with the incarcerated who write biographical stories, which are turned into plays performed by the prisoner-authors and OSU students.

Empathy, humanity and compassion — that’s what Jinks says she is trying to accomplish working with prisoners in John Lilley Correctional Center, a men’s minimum-security prison in Boley, Okla. Jinks, through ArtsAloud-OSU, wants to show that people in prison are human beings just like anyone else, except they’ve made mistakes and are paying the price.

Jinks leads classes of prisoners where participants write based on prompts or topics related to their lives that allow them to share who they are — stories of childhood, parents, choices and the circumstances that led them to where they are.

“Anything is valid. I allow for anything to be written about,” says Jinks. “They’re learning through the stories that their experiences are universal. I’ve heard them say they feel like human beings in the ArtsAloud classes.”

The stories are performed by the prisoners for their fellow inmates in the prison’s general population. Jinks also shares the stories with her students at OSU who adopt the roles of the men and rehearse the performances on campus. Then Jinks takes them to John Lilly where they “give back” the stories by performing them for the inmates who wrote them.

In her TEDxOStateU talk in 2015, Jinks described the give-back through the experience of one of her students who was asked by a prisoner if it felt dangerous to be there and perform their stories. The student replied that they were scared, but only because they didn’t want to mess up the life stories entrusted to them.

“The prison students see their stories come to life through the OSU students,” Jinks told her TEDx audience. “And the students recognize the prisoner’s humanity and understand how razor-thin the line between incarceration and freedom can be.”

Jinks has explored that line through ArtsAloud from the time she started the prison theater program in 2005 while teaching in Austin, Texas. There, she worked with female prisoners and often asked herself what the difference was between these incarcerated women and herself? What allowed her to pursue her dream of being an artist while these women were denied the opportunity to follow their own dreams? Because of that experience, Jinks dedicated her career to giving a voice to the incarcerated through theatrical performance. She has tried to introduce the program in women’s prisons in Oklahoma, but so far has by denied access been the state Department of Corrections.

Jinks is practicing what is called applied theater — applying theater practices in nontraditional situations and venues, such as a prison. The concept is global; Jinks tells the story of a man from Manchester, England, who uses theater as conflict resolution between warring groups in Africa.

This summer, Jinks traveled to Italy to spend time with Vito Minoia, a professor at the University of Urbino, who created a prison theater alliance there that works with the incarcerated and the mentally ill. Participants perform plays with local actors and students in surrounding communities.

“I saw this amazing piece of theater written and performed by prisoners who were released for the evening and who worked with a group of actors,” says Jinks. “It was beautiful.”

Inspired by the experience, Jinks said she returned to Oklahoma to continue her work to “reveal the soul of the prisoner.” Jinks and many others believe allowing the incarcerated to express themselves creatively can ease their transition back into society and reduce recidivism. She is working with OSU psychology professor Shelia Kennison on a survey of prisoners involved in ArtsAloud to collect data about self-compassion. They are waiting for Department of Corrections approval to conduct the survey.

“Performance is a way to talk about being human,” Jinks said in her TEDx talk. “I believe that connection with one another leads to empathy and with increased empathy and self-respect, it becomes more difficult to hurt others or yourself.”

Jinks hopes to one day expand ArtsAloud to all prisons in the state, but she needs more trust and confidence among prison administrators for that. She also wants to work with released prisoners and their families and continue to tell their stories in performances done in public spaces such as parks, schools and libraries, and at community events like festivals.

“I’m trying to educate and inform so that people in Oklahoma, which has the fourth-largest prison population in the country, can experience how similar so many prisoners are to themselves regardless of skin color and economic status,” Jinks says.

For more information, visit artsaloud.okstate.edu/.

Story by Jeff Joiner