All in this together: OSU veterinary researchers study animal health to aid in human medical advances

Tuesday, September 19, 2023

Media Contact: Harrison Hill | Senior Research Communications Specialist | 405-744-5827 | harrison.c.hill@okstate.edu

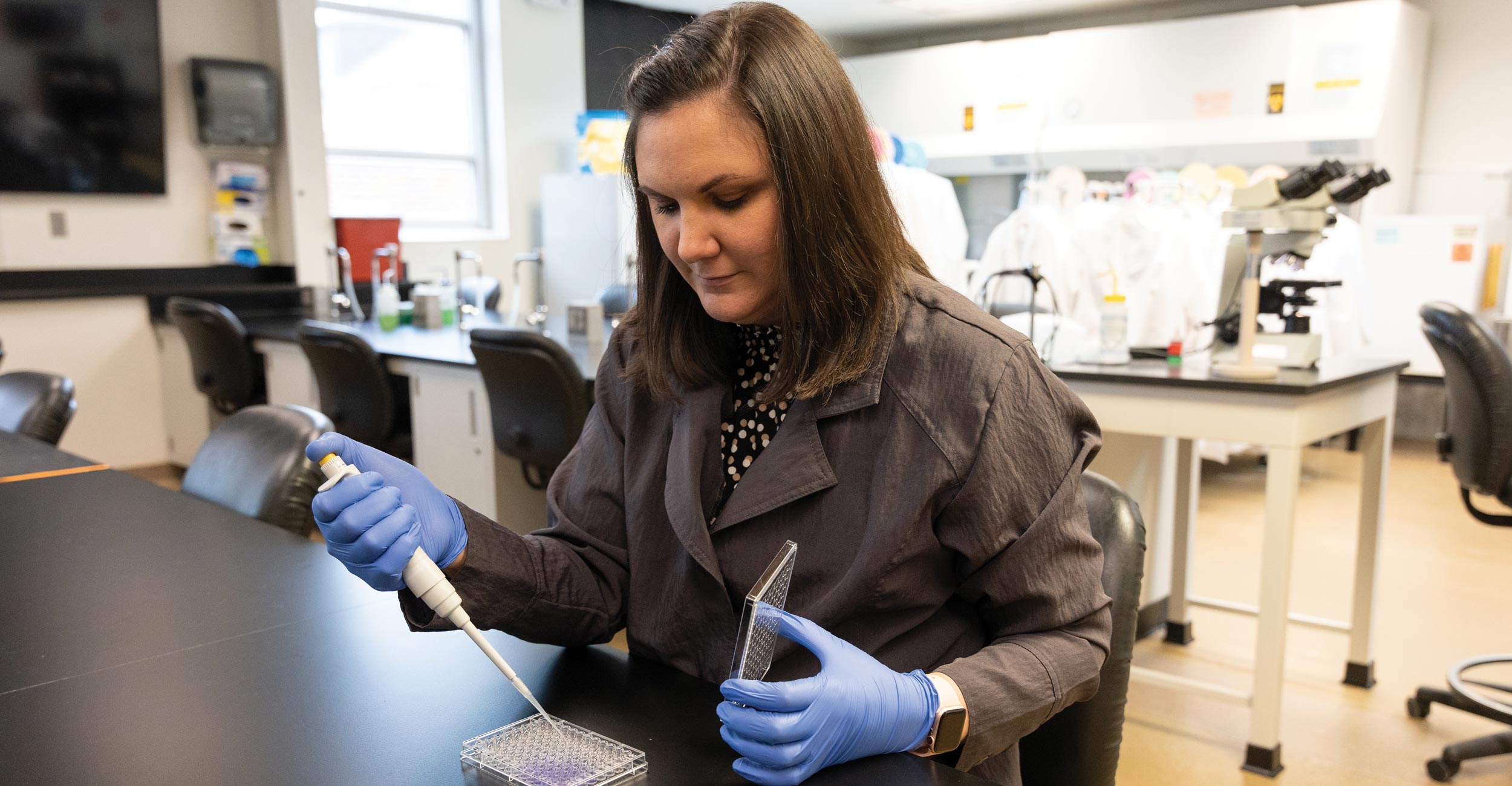

Being a veterinary microbiologist doesn’t mean exclusively working with animals.

At least that’s what Dr. Jennifer Rudd, an assistant professor of veterinary pathobiology at Oklahoma State University, has discovered. Rudd’s research began with studying influenza, which led her to work with a combination of humans and animals. She was already in the depths of researching influenza as a potential pandemic situation when COVID-19 spread worldwide in 2020, giving her a perfect opportunity to shift her focus.

“There was a subset of us who had this unique background, this expertise that was already sort of ready to go to work in pandemic viral respiratory disease,” Rudd said. “I was one of the pieces that fell into that right away.”

When Dr. Craig Miller, a former assistant professor at OSU, received a grant for his lab to work on researching the pandemic, Rudd was brought in. She helped with the clinical aspects of the research and developing the models.

Rudd’s background as a veterinarian gave her an extra boost after learning that COVID-19 affects cats as well as humans. The disease naturally infects cats, so using them as a model better helped her understand how COVID-19 works in people. Miller said preliminary findings show there is potential for evolution of the disease, and that they are hoping it becomes more like the common cold over time as people gain access to vaccines and build natural immunity. Whether that would make it more or less transmissible, they aren’t sure, but they say they are sure people will adapt.

In the initial findings, Rudd said one of the most interesting things they found was how similar COVID-19 is between SARS-CoV-2 infected humans and cats. Although the disease typically isn’t severe in most cats, there is a range of outcomes, including several documented deaths in large cats in zoos. So, after this discovery, Rudd said the researchers were excited to know how many questions they could answer by being able to mimic the disease.

Research starts at the laboratory bench with basic research and development of ideas before studying these in animals. From animals, these findings can be translated into preclinical studies and then clinical trials, where they can help humans in real world settings.

Miller said they are trying to bridge the gap between the research discovery phase and the clinical phase. In that preclinical space is where their models come into play. There, they can adapt the model to a translational aspect that allows them to use cats to better understand what’s happening in humans.

“There’s that interplay between animals and humans that we can really explore to extrapolate new findings and new methods to try to help humans while also helping animals at the same time,” Miller said. “That’s how I envision One Health. We’re all in this together and we can use these different aspects to try to help different factors or different sectors of the health spectrum.”

Through this study, Rudd and Miller have emphasized the idea of One Health. The idea that the health of humans, animals and the environment are all interconnected drives much of the research in the veterinary world.

“If any one of those three pieces is struggling, there are direct and indirect implications on the other two,” Rudd said. “Instead of trying to do our research with blinders on and only look at veterinary medicine, or human medicine, or environmental medicine, there’s a push to take a more holistic approach, which is more applicable, more practical and has more ability to change. We can understand how this expertise and these different areas can work together to make each other better.”

For example, Rudd said there are cancers in dogs that veterinarians can use to create therapies that translate over to people. The Institute for Translational and Emerging Research in Advanced Comparative Therapy, a group in the OSU College of Veterinary Medicine, has projects of One Health through cancer research such as this.

Rudd, however, works in coronaviruses and said animals have been getting coronaviruses much longer than the ones people have been studying in human medicine.

“There’s always a question of what if. What if we had a better One Health approach or what if we’d have more veterinarians involved in early 2020?” Rudd said. “Would it have been slightly different? And I think we all need to learn from that and remind ourselves that we all have our areas of expertise. But we’re all better when we’re unified and working together as opposed to staying in our silos.”

Photos By: Taylor Bacon

Story By: Mak Vandruff | Research Matters Magazine