Link to the Past: Medieval manuscripts exhibit teaches OSU students, faculty evolution of publishing

Tuesday, September 19, 2023

Media Contact: Harrison Hill | Senior Research Communications Specialist | 405-744-5827 | harrison.c.hill@okstate.edu

Eight hundred years ago, in a country that most likely has a different name now, a goat was killed.

Everything from the goat was used for all manner of things in the Middle Ages, but everything eventually disappeared through time, except for one thing: its hide.

The hides of many animals were used to create parchment, which then went through a variety of different people who wrote, illustrated, bound and distributed the final product as a book.

Some of those books showed up this spring at Oklahoma State University as part of an exhibit of medieval manuscripts, still intact.

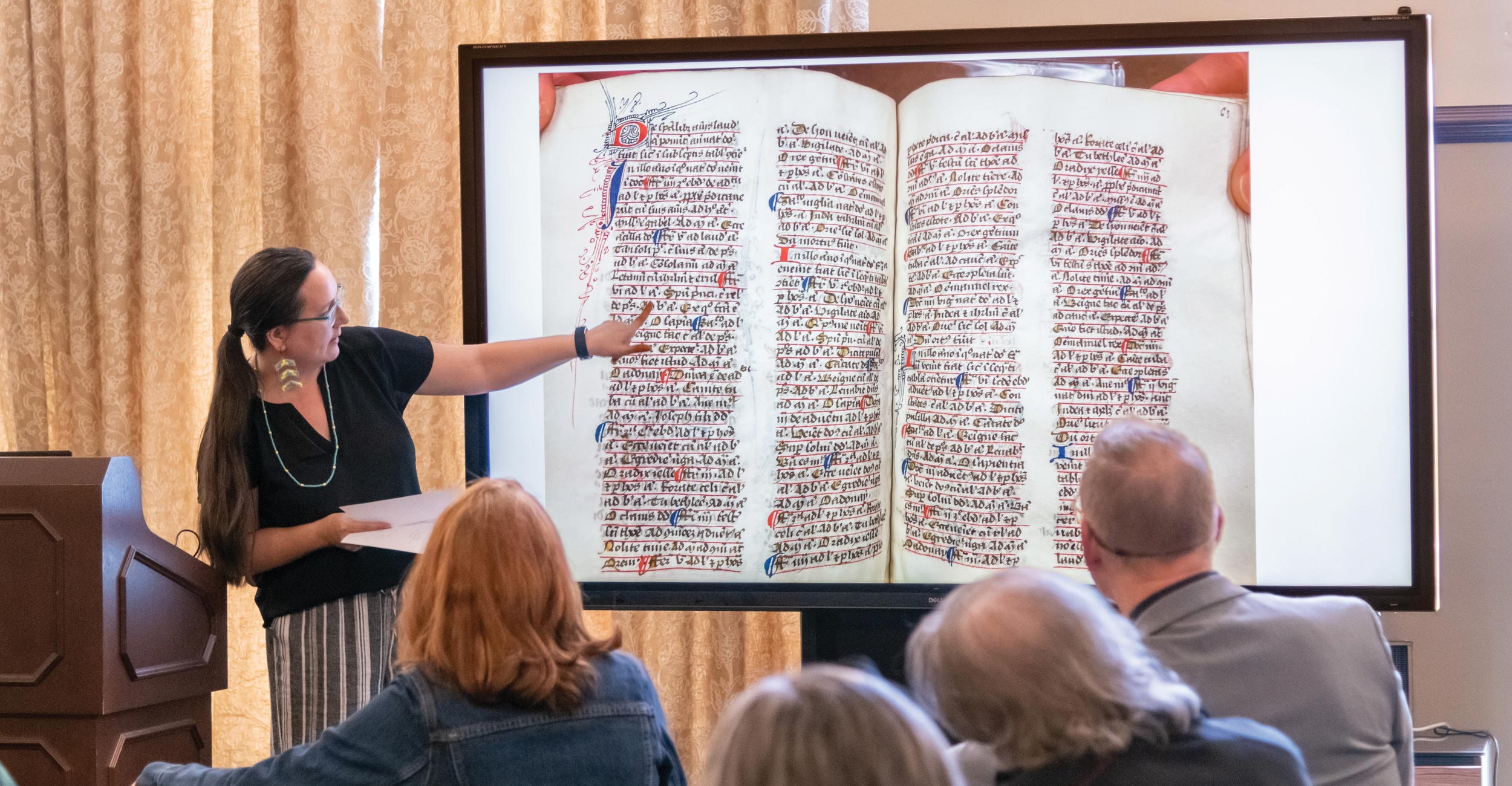

The exhibit, on loan from gallery Les Enluminures, captivated the minds of OSU students, faculty and the public with the craftsmanship of the manuscripts and the writings in them that have stood the test of time.

Dr. Jennifer Borland, an art history professor and director of the OSU Center for the Humanities, said the talks with the gallery to receive the books as part of the Manuscripts in the Curriculum program started in 2018. However, because of COVID-19, the exhibit didn’t come to fruition until 2023.

Borland, Dr. Emily Graham in the Department of History and Dr. Mary Larson in the Library were instrumental in the exhibit coming to OSU.

“If you look at the cost of the materials that we had here, I think it was close to half a million dollars worth of manuscript material,” said Larson, the Puterbaugh Professor of Library Service and associate dean for distinctive collections.

Before anyone could view the materials, the Library had to ensure all the conditions were right for viewing. The manuscripts were mailed through FedEx, Larson said, and the utmost security and care was taken for them upon their arrival.

“Before we could even get the exhibit, we had to track environmental conditions like temperature, humidity, changes within a 24-hour period, all of that in the areas where the manuscripts would be held. We had to do all of that for a number of weeks,” Larson said. “… We had to put UV filters on all of our lighting to make sure that the manuscripts aren’t getting too much.”

Larson, who has a background in archeology, was tasked with a condition report of the materials when they arrived and writing one when the manuscripts were sent back.

“There was a Vulgate Bible that we had on loan and it was like onion skin,” Larson said. “I have never seen parchment that thin in my life. The size of the calligraphy, the print, the text was just tiny, even with my glasses. I pictured some monks slowly going blind copying this because it was astonishingly small and very fine.”

Larson enlisted the help of Ben Hedges and Sana Masood in the Department of Special Collections and University Archives to help. For all three, the manuscripts were the oldest written materials they had handled. (The oldest materials in the Edmon Low Library are in the Dr. Bill F. and Jean Kelso Collection of Ancient Coins as some of those date to the fourth century B.C.)

“You find yourself in awe of them at first, just seeing the kind of history that’s sitting in front of you,” Hedges said. “And then your first instincts are also to just treat them as if they’re going to disintegrate if you look at them wrong but, in reality, they’re actually pretty hardy, they’ve survived upwards of 800 years.”

The manuscripts were kept in a safe when not on display, but otherwise, students were briefed on how to handle them when they would come to study. Hedges said one misconception was that gloves needed to be worn to work with the books, but that is not the case since they could tear the parchment more easily.

Most of the books were in Latin, and though the writing was still legible, the text wasn’t as important to many students and faculty as the construction of the manuscripts and the ways in which the texts were written with artistic flourishes and paintings. Borland said not only did the history and art history students glean knowledge from them, but so did graphic design students and even agriculture students because of the parchment-making process.

“I think there’s a number of individual examples that can very much connect to what people are doing today in their specific spheres of research, reminding them that what they’re doing is kind of built on a centurieslong set of traditions, be they artistic, or agricultural or something else,” Borland said.

With her expertise in medieval art and architecture, Borland said she sees in her research a variety of modern things that still carry over from the Middle Ages. Renaissance fairs and pop culture such as “Game of Thrones” keep some medieval ideals in the mainstream, but Borland wants to ensure people understand the whole context of the times. The manuscripts were able to help with that.

“There’s some really interesting ways in which medieval things pop up in modern culture, and we want to give our students a way to process that, to identify it, to question it, to not just assume that it’s an accurate representation,” Borland said.

Borland’s graduate students each picked one manuscript to study and present on. Throughout the semester, Borland had them inspect the materials page by page, seeing different qualities in each book and how they differed in how they were built. For instance, the Vulgate Bible was a highly valued text and therefore had more care put to it than other texts which might have featured parchment that had been reused from a different book entirely.

While looking at the parchmentmaking process, Borland brought in Jesse Meyer, a tanner in New York who explained to students how parchment is made today.

“I think understanding the labor and materials and production is something that can help us understand how we’ve changed over time, the parchment is a good example of a productive conversation,” Borland said.

Vinita Williams, a graduate student of Borland’s who earned her master’s degree this summer, said it was interesting to see how books had been repaired when they had been damaged. For the people who could afford books at that time, they were treasures.

“You might see a little scar, or you might see a hole when they accidentally sliced it or cut it when they skinned the animal,” Williams said. “And then when they stretched it out, and it dried, it created a hole. And so, what was interesting is to see how, and there are different ways that they might have handled that. Sometimes you will see where they’ve written the script, around the hole, and we had a couple of books where they actually repaired it with embroidery thread.”

Williams researched the Book of Hours and presented it with her fellow graduate students on April 18. She studied if women had anything to do with the production process of the manuscript or if a woman had owned it.

Although the manuscripts were a window into the past, they also very rarely mentioned contemporary women or peasants for that matter, as history at the time was written about the upper class. These manuscripts were all from a European point of view, so students had to read between the lines to see more about the times when the books were written.

“There is evidence of women artists in those times,” Williams said. “But for most of it the huge majority of the work, none of it is signed. We don’t know for sure. The only way they can tell what workshop something came from is because people have their own style, or something unique to them.”

Despite having the manuscripts for the whole semester, Borland said there were still students who said they would have loved to study them more. She is working with the Library on possibly fundraising to get a permanent collection at OSU.

“You find yourself in awe of them at first, just seeing the kind of history that’s sitting in front of you. And then your first instincts are also to just treat them as if they’re going to disintegrate if you look at them wrong but, in reality, they’re actually pretty hardy, they’ve survived upwards of 800 years.”

“It gives students an opportunity they don’t get otherwise; like the only other time you know people at OSU would have to see material like this is behind the glass at a museum and sometimes an exhibit,” Masood said. “This was getting up close, being able to really look at them, sometimes they get to handle them, it’s a rare opportunity.”

The benefit of having materials up close, like OSU was able to have this spring, was beneficial and something Borland said you can’t get just by looking at a computer screen.

“You can understand certain things from very high res, digitized images,” she said. “But you can’t sense the weight of the book, or how the pages turn or what noises happened, to engage with it, how it smells, and all these things. There’s this kind of sensory physical experience, and I think of it really linking directly to the past, when you touch something that someone in the 13th century also touched.”

Photos By: Jason Wallace and Nina Thornton

Story By: Jordan Bishop | Research Matters Magazine