OSU-Tulsa commemorates the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre with truth, transformation and education

Wednesday, August 25, 2021

Media Contact: Mack Burke | Editorial Coordinator | 405-744-5540 | editor@okstate.edu

Oklahoma State University-Tulsa, in partnership with OSU-Stillwater and OSU Center for Health Sciences, is commemorating the 100-year anniversary of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre with 100 Points of Truth and Transformation. The 100 Points represent opportunities to connect with the truth of the massacre and be inspired toward transformative justice.

Since June 2020, the 100 Points of Truth and Transformation initiative has offered conferences, film screenings, author talks, book clubs, classes, podcasts, writing workshops, art exhibitions and community healing rituals to educate and energize the public — with more opportunities for truth and transformation planned well beyond the centennial.

When Alana Mbanza moved to Tulsa from Chicago in 2020, she had only recently heard of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Although she had a master’s degree in African American studies, the events of the massacre were mentioned only briefly in one of her classes.

“Nobody was talking about this,” Mbanza said. “It just goes to show that even deliberately seeking out history is not enough sometimes.”

The massacre, previously referred to as the misnomered Tulsa Race Riot, took place May 31-June 1, 1921, when a white mob attacked and destroyed the Greenwood District, a prosperous Black neighborhood in Tulsa. Historians estimate up to 300 lives were lost, with thousands more injured and left homeless. Thirty-five blocks of the district — once called the Black Wall Street — were burned down. OSU-Tulsa is located on part of the land that was ravaged by violence a century ago.

“When I moved here, I didn’t know much,” Mbanza said. “It wasn’t until I tooka tour and learned that I lived across the street from where the massacre started that I was like, ‘wait a minute — I need to know more.’”

She signed up for the Writing About Greenwood virtual workshop, offered through the Center for Poets and Writers at OSU-Tulsa as part of the 100 Points of Truth and Transformation.

“I’ve learned so much. I had seen some images in the papers, but to take a deep look at some of the photos in the historical archives for the first time has been powerful,” she said. “It felt more like a community group than a workshop. It was a writing class, a history class, a therapy session — all wrapped up together.”

She became involved in more Greenwood community initiatives and returned to OSU-Tulsa’s campus as a volunteer for the John Hope Franklin National Symposium.

Mbanza’s path to learning the truth of the massacre is not unusual. Many Tulsans only learned about the tragedy as the centennial commemoration approached and sparked news coverage, documentaries and pop culture ties such as HBO’s Watchmen series, which propelled the anniversary into the national spotlight. President Joe Biden drove through parts of the OSU-Tulsa campus on June 1 to visit the neighboring Greenwood Cultural Center, where he called for the United States to “come to terms with” the darkest moments of its history.

Before this attention, discussion of the massacre was rare. Many Oklahomans were not taught about it in history classes. The events were only added to Oklahoma Department of Education required curriculum in the fall of 2020.

“There has been an extreme and largely unaddressed need for education related to the massacre,” said Dr. Pamela Fry, president of OSU-Tulsa. “As a university that is located in Greenwood, we recognize we’re on sacred land. It’s our ethical responsibility to be an access point for the truth of what happened here as well as a champion for understanding and transformational change.”

With that responsibility in mind, 100 Points of Truth and Transformation was created to increase education about the history of Greenwood as well as for OSU-Tulsa to grow as a community partner.

“We want to serve as an anchor for north Tulsa,” Fry said. “These opportunities are about access, service to the community and programming; 100 Points is just the beginning.”

That community responsibility is recognized across the Oklahoma State University system.

“Broadly speaking, this is the business we’re in as a higher education institution: teaching the truth, and building trust and relationships,” said Dr. Jason F. Kirksey, vice president for institutional diversity and chief diversity officer at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater. “Having dialogues and conversations that help move us forward is an important part of our responsibility.”

OSU-Stillwater students, faculty and staff have taken note of the 100 Points. The O’Colly Media Group created a full-length documentary, an American studies class created an interactive virtual timeline of Greenwood events and a history class created a website to host essays and biographies about the Black women who shaped Black Wall Street. Other opportunities produced in Stillwater include a podcast, a virtual candle lighting for civil rights pioneer Nancy Randolph Davis and a live Q&A with state Rep. Mauree Turner.

“As a land-grant university, the 100 Points certainly align with our mission of improving the quality of life of the citizens of our state,” Kirksey said.

For Mbanza, the opportunity to connect deeply with the history of her new city has kept her rooted here.

“I’m here in Tulsa for a reason. I didn’t know what that was when I first moved, but I think it’s to learn and participate in things like this,” she said.

Mbanza originally moved to Tulsa as part of the yearlong Tulsa Remote program, but she has since bought a house in town and dedicated more of her time to volunteer work.

“I feel like I’ve recruited 10 people to move to Tulsa,” she said. “There’s a lot happening here, and there’s still a lot to be learned and discovered and shared.”

Telling the Truth

The Tulsa Race Massacre impacts and influences the lives of Tulsans in more ways than many realize.

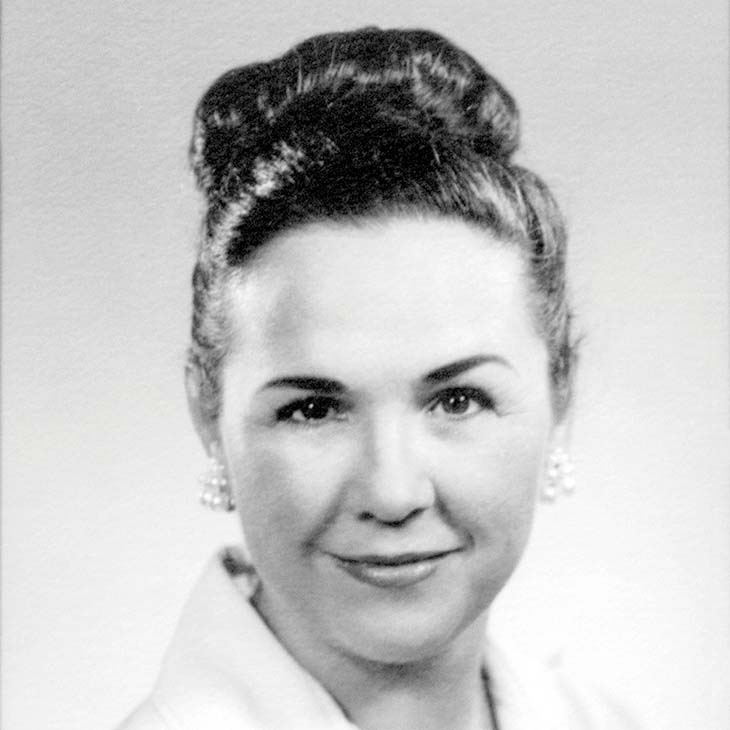

After she learned about the massacre, Lynn Wallace was inspired to pursue a lifelong career discovering and documenting information about it.

In 1985, Wallace and nine of her fellow Girl Scouts undertook a genealogy assignment for their Gold Award project. They were tasked with cataloging headstones in Tulsa graveyards, which included making gravestone rubbings and creating a detailed written record. The result was the book Shadows of the Past: Tombstone Inscriptions in Tulsa County, Oklahoma.

Wallace was assigned Oaklawn Cemetery, a site long rumored to house mass graves of massacre victims. The city of Tulsa began a search for mass graves at the site in 2020 and recovered human remains in 2021. Thirty-five years prior, Wallace and her troop heard about this possible mass grave from the groundskeeper — which was also the first time she was told anything about the massacre.

“That was a pivotal project for me, and it’s what led me to become a librarian,” Wallace said. “It showed me the importance of documenting and preserving history.”

Wallace is now the director of the OSU-Tulsa Library, which is home to a significant archive of Tulsa Race Massacre content: the Ruth Sigler Avery Collection — Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

Avery witnessed the massacre at 7 years old. In the 1960s, she began processing the trauma of her experience by writing about what she witnessed in detail, describing Black bodies piled on wagons and Black men shot in front of her. The OSUTulsa Library’s collection is an archive of her research and manuscript, which contains written and recorded interviews from survivors, witnesses and city officials. The archive also contains original and reproduced photographs.

“It’s a collection of work that can’t be done today,” Wallace said. “Many of the voices on those tapes have passed on. What’s left is the archive, and it’s our job to preserve those stories.”

Avery, who never published her work, was one of the first scholars to start collecting this information, predating groundbreaking works by the likes of Eddie Faye Gates, Tim Madigan and Scott Ellsworth. The collection was donated to the OSU-Tulsa Library in 2004 by Joy Avery, Ruth’s daughter.

“I am always grateful to the patrons of libraries in general, but especially to Joy,” Wallace said. “Her decision to donate her mother’s work has really clarified the truth of the events of the massacre. A lot of what we know about the massacre today comes from those interviews.”

For OSU-Tulsa, the archive is another way to give agency and voice to those who didn’t have any at the time.

“We had a grandson of a survivor come in and hear his grandfather’s voice for the first time on a recording,” Wallace said. “That’s powerful. That’s the impact of the archive. It’s been an honor of a lifetime to make Ruth’s work available, to have the opportunity to share her story and stories of so many others who were here 100 years ago.”

Going beyond the task to preserve the testimonies of the massacre, the library is dedicated to helping people connect with the documented truth of those events.

“The OSU-Tulsa Library is built on hallowed ground,” Wallace said. “It’s our responsibility to make this archive, the words and photographs of witnesses and victims, accessible to anyone.”

Since the Ruth Sigler Avery Collection was donated to the OSU-Tulsa Library, more than 170 media outlets and artists have made use of its photos, interviews and resources. Multiple books, National Geographic, The Washington Post, The New York Times, the BBC and several documentaries and artists have utilized the collection, which is open to the public.

Tulsa artist, photographer and filmmaker Patrick McNicholas is one of many to make use of the archive. He’s the mind behind the “Time-Travel Tulsa” project, a visual art series that blends historic photographs with images of their current-day location.

In 2018, he started focusing on historic photography with a series called “20 for ’21” — initially a project to colorize historic photographs and create animations that transitioned between the colorized and blackand- white images. When a coworker posted an old photo side-by-side with a present-day image of the location online, McNicholas decided to blend the two images together, and his idea for the composite photo series was born.

“People have seen the historic photographs of the massacre,” McNicholas said. “But when you see it in context, it absolutely highlights the magnitude of the destruction.”

After the massacre, Greenwood was rebuilt but was demolished again for the construction of I-244 and the city’s urban renewal program. Almost no original structures in Greenwood remain.

As a historian, McNicholas was especially interested in knowing the circumstances of each photo and displaying them with that frame of reference in mind. He took OSU-Tulsa’s Black Wall Street History class to gain a deeper understanding of Greenwood’s history.

“You can read books on your own and learn a lot, but I knew the opportunity to take a class from OSU-Tulsa and have conversations with classmates and an expert professor would offer a more refined and scholarly perspective for my own projects,” he said.

In the class, McNicholas researched and discussed how Black Wall Street was built, destroyed and rebuilt.

“The class helped me understand Greenwood at a deeper level and the people who built Greenwood,” McNicholas said. “Reading some of those testimonies, it’s hard to realize how warlike the massacre was.”

The course also offered him opportunities outside the classroom to continue his work. The connections he made in the classroom ultimately culminated in his photos being displayed in an exhibit at the Philbrook Museum of Art. That exhibit opened doors for other exhibits, and even a production assistant role in the History Channel’s Tulsa Burning documentary.

Although his photo series has kept him busy, McNicholas has made a point to avoid profiting from the subject matter. When he does sell prints, a portion of the proceeds are donated to the Black Wall Street Alliance, an organization in Greenwood dedicated to uplifting the district’s legacy. Ultimately, he’s just grateful his art is making an impact.

“There’s so many ways to tell the history of Greenwood, but you can’t deny the power of seeing it for yourself,” he said.

Progress Toward Change

Though the centennial commemoration of the Tulsa Race Massacre has passed, Oklahoma State University’s work is not over. OSU-Tulsa, OSU-Stillwater, OSU Center for Health Sciences and other community partners continue their commitment to educating about the events of the massacre and their lasting impacts. OSU-CHS has also been focused on addressing barriers that result in a lack of Black doctors.

“Living in peace should be something that we continually strive for,” said Brenda Davidson, assistant dean of diversity at OSU-CHS. “Everyone deserves unconditional acceptance and respect and to stand up for what one believes in, while also respecting those who might disagree with one’s viewpoint.”

For Davidson, the 100 Points of Truth and Transformation is a way to not only commemorate the victims of the massacre, but also to help students grow into empathetic professionals.

“We might not always have the same perspective, but we can always be respectful and kind to one another,” Davidson said.

“What’s important to me is that we are arming our students with as much knowledge, perspective, vision and empathy as we are capable of,” said Quraysh Ali Lansana, director of the newly established Center for Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation at OSU-Tulsa.

The center is part of a nationwide, community-based initiative by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation to plan and bring about transformational and sustainable change and to address the historic and contemporary effects of racism.

“I see the 100 Points as an opportunity to build well-rounded, thoughtful and passionate people, inside and outside of the classroom. We’re engaging with people who will inherit the responsibility of running this country,” Lansana said.

Lansana has extensively researched and written about Greenwood and the massacre and moved to Tulsa specifically for the opportunity to fully engage with the history of Tulsa’s Greenwood District.

“Over the course of about 16 years, Black Oklahomans built an incredibly successful city within a city, rooted in faith and determination, in the face of some of the most severe Jim Crow laws in all the country,” he said. “What they built was lost, but we can help nurture that same spirit around us.”

Since assuming his role with the center, he’s hosted a monthly Facebook live conversation series, participated in faculty panel discussions and published a children’s book, Opal’s Greenwood Oasis, which is set set in historic Greenwood. He also has taught, organized or hosted many events, including the Writing About Greenwood workshop and the Black Wall Street History class.

Through the Center for Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation, Lansana works closely with the community to create programs and initiatives that benefit north Tulsa and engage the OSU-Tulsa campus community.

“There’s an invisible wall that exists between most universities and the community around them that sends signals that the community is not welcome,” Lansana said. “We’re working to erase that wall. As a resource, OSU-Tulsa has a tremendous number of assets — human and otherwise — to offer north Tulsa.”

One of the leaders working to dismantle that invisible wall is Emonica “Nekki” Reagan-Neeley, assistant vice president for community engagement and student services.

“We have a responsibility, because of the ground we’re built on, to commemorate and teach the history of Greenwood, but it’s also an opportunity,” she said. “We have a chance to amplify and educate everyone around us. When we serve the people around us, we’re planting seeds that will grow with us.”

Reagan-Neeley’s community engagement team has launched several free and low-cost events and programs designed to educate and enrich the lives of OSU-Tulsa neighbors in the Greenwood District. Recent initiatives include a STEM Force workshop, a Saturday school, several literacy events and a 24/7 community library. Programs like these provide not only a service for the community, they also help create a more accessible college campus.

“We want the community on campus,” she said. “We want them to tell their friends, their teachers, their churches, that they learned something inspiring at OSU-Tulsa, and hopefully it will empower them to return here to earn a degree.”

The programs and events offered as part of the 100 Points of Truth and Transformation — most open to the public, and the majority at no cost — have given countless people ways to access OSU and the truth of the massacre. In Reagan-Neeley’s eyes, providing that service is a step on the path toward healing in Greenwood.

“As an institution, we are part of this community,” Reagan-Neeley said. “We’re here. And we all have to face the truth to start the transformation.”

A Brief History of the Land

Greenwood was rebuilt after the Tulsa Race Massacre. With no aid from the city and insurance claims denied, the community worked hard to restore what was destroyed, and many Black businesses and homes returned stronger than ever. In fact, it wasn’t until after the massacre that Greenwood became known as the “Black Wall Street of America.”

In the 1960s and ’70s, construction of four federal highways signaled the end of Greenwood’s second wave of prosperity. “Urban renewal” claimed land for the highway system, removing homes and businesses to create U.S. Highway 75 and Interstate 244.

In 1986, the city’s redevelopment arm opened the land just north of the highway to create a higher education campus, University Center at Tulsa. Initially, UCAT was composed of Langston University, the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma State University and Northeastern State University providing academic offerings on campus. Since 1999, only OSU-Tulsa and Langston University remain.

Photos By: Aaron Campbell and Patrick McNicholas

Story By: Aaron Campbell | STATE Magazine