Cowboy Chronicles: Look on OAMC campus during WWI

Wednesday, August 31, 2022

Media Contact: Mack Burke | Associate Director of Media Relations | 405-744-5540 | editor@okstate.edu

Editor’s note: This article is the second part in a series about life at OSU leading up to and during World War I. See part one here.

When the United States officially entered the Great War on April 6, 1917, the pace of military preparations increased dramatically on the Oklahoma A&M College campus.

Additional resources were immediately devoted to address the agricultural, military and engineering requirements of the nation. The college would quickly discover challenges both at home and abroad.

Students essential to their family’s farm operations were allowed to leave classes on April 26, 1917, and return home. For the next 18 months, OAMC President James Cantwell, serving on the local draft board, received hundreds of letters from parents requesting draft deferments for male students allowing them to remain on family farms.

In May, former OAMC students who had been part of the Corp of Cadets began leaving Stillwater for training camps in Arkansas and Texas. The first group of 82 left for Little Rock and additional instruction. College employees and remaining students joined them for a formal farewell ceremony at the flagpole south of the Central Building the day before they left.

This assembly of student soldiers already had experience digging trenches, building temporary bridges, reading maps and living in military style camps. As part of their training on campus, they had resided in camps placed east of the athletic fields. Larger crowds representing the college and community gathered at the Stillwater Railroad Depot over the next 18 months as other groups left for military training and service in Europe.

As the campus reconfigured its student services, some changes were more obvious than others. “Big” Ben Banks, director of food services, instituted a food conservation program and worked closely with groups planting “Victory Gardens” to ensure their produce would be integrated into the cafeterias on campus. These gardens, started years earlier, dramatically increased in size during the war and the OAMC Extension service shared improved food preservation techniques on campus and around the state.

Entomology professor C. E. Sanborn developed a beekeeping class to promote the production of honey and help families deal with the sugar shortage. It may have been the first correspondence course the college offered. The agricultural experiment station on campus encouraged farmers to experiment with additional feed crops including cotton seed, corn and potatoes.

A faculty shortage required some to teach classes on the periphery of their expertise. Dairy science professor Arthur C. “Teddy” Baer taught classes in chemistry and bacteriology. Physical education director Edward Gallagher, who had just started coaching wrestling a year earlier, volunteered to teach wrestling to military cadets for selfdefense situations in hand-to-hand combat. Gallagher also organized a new event in the annual state interscholastic competitions. The new contest involved throwing a hand grenade for accuracy and was described in the college newspaper:

Throwing hand grenades will be a new and novel feature of the 10th annual State Interscholastic track and field meet, to be held in Stillwater, May 3 and 4, under the auspices of the Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College. Coach Gallagher is now arranging for the contest. The throwers will stand in a trench 6-feet deep by 3-feet wide and will hurl the grenade from 100 to 125 feet at an area 10-feet wide and running parallel to the trench. Accuracy and not distance will be the aim of the throwers.

Women on campus expanded their active roles in the war effort, becoming more involved in student government and campus publications (a similar movement unfolded two and a half decades later during WWII). They participated in military training, sold Liberty Bonds and War Savings Stamps, established a campus Red Cross chapter, created a student loan fund, and wrote letters to classmates training stateside and serving overseas. Letters received from OAMC students in the trenches in France were printed in the Orange and Black, but there were very few other newspaper stories about the war.

Cadets were able to purchase better uniforms as they prepared for war. The new uniforms were U. S. Army regulation, higher quality material, lasted longer and held their shape better. A former commandant claimed he has worn his for 10 years. The band was also able to purchase military style uniforms to match.

Bohumil Makovsky had only been on campus a few years before the war started, but he had developed an excellent reputation as director of the military marching band and conductor of the orchestra. The marching band accompanied cadets during drill and parades, both on and off campus, as well as participate in supporting many athletic events.

Intimidation, misunderstanding and suspicion led to several difficult situations on the OAMC campus and in the Stillwater community. Captain C. D. Dudley, who served as commandant of the cadet corps, accused Makovsky of performing music at a campus performance with “a German patriotic air.” Dudley documented other Makovsky “infractions” in extensive correspondence with President Cantwell.

Stillwater dentist F.R. Greene accused Gustav Friedrick Broemel, head of the foreign languages department and a distinguished professor, of poisoning students’ minds. The Germanborn Broemel had studied at Leipzig University and the University of Kiel but was a well-known and respected faculty member at the college and active in a number of organizations. Mrs. Broemel was a patient of Greene’s.

Assembling information gathered from conversations, local gossip and his other patients, Greene wrote to the editor of The Daily Oklahoman, Walter M. Harrison, accusing the couple of aggravated disloyalty. The state health commissioner, Dr. John W. Duke, wrote directly to Gov. Robert Williams that the Broemels “had made themselves quite obnoxious to all the loyal citizens in that community.” Duke went on to inform the governor that the German Kaiser’s picture “hangs in their sitting room.” None of it was true, however.

Another member of the foreign language department and close friend of Dr. Broemel, Almon Arnold, also was accused of disloyalty based only on local gossip that he spoke German fluently. Fritz Wilhelm Redlich, originally from Stuttgart, Germany, was a member of the architecture faculty. He fell under suspicion simply because of his name, place of birth and accent.

Harrison felt the charges were unsubstantiated. Though pressured by Gov. Williams and Board of Agriculture Regent Frank Gault to fire any disloyal employees, Cantwell refused to fire or reprimand Broemel, Arnold, Redlich or Makovsky on such flimsy accusations. But all 14 German language and literature courses were eliminated from the fall of 1917 through the 1919 calendar year. Broemel was heartbroken, he resigned from the faculty and his family moved to Chicago, where he died the following year at age 56.

Student military training continued on campus under Sgt. Maj. Michael McDonald. He was in charge of the Reserve Officer Training Corps, Military Science and Tactics. He worked closely with 1st Lt. George W. Ewell, who was commandant of students until called into action. Ewell and McDonald ran their student soldiers through competitive exercises and “sham” battles.

One newspaper article described such an event: “It was a bright crisp day in May when A&M’s regiment went forth to war. One would not think that the students of an institution would stand up and calmly shoot each other down — but that’s the way they do it in Oklahoma.”

The sham battle produced excitement, exhaustion and sometimes desertion. Female students cooked meals, held picnics and observed the events unfold as the male cadets dug trenches, marched through wooded farms and fired their rifles while wearing gas masks. After the battle concluded, the officers led the cadets to the closest pub where they enjoyed a round purchased by the defeated side.

Ewell and McDonald also provided military training for general students wanting to become teachers. This was in response to a state board of education mandate that all teachers in the rural schools, high schools, state normal schools, universities, the state training schools and the Oklahoma State School for Dependent or Orphan Children were to teach students eight years or older military training at least one period each day.

Gov. Williams suggested replacing sports programs in all schools with military training. He stated, “I am going to propose a measure in the next legislature to abolish football and baseball in all state schools and institute military training instead of athletics.”

President Cantwell also had impressive plans in mind for physical changes on campus. He proposed construction of a new science building and new gymnasium. War efforts delayed construction on both projects, especially the purchase of steel.

With the expanding military training programs on campus, Cantwell suggested that the new physical education facility be renamed the Armory and Gymnasium. This simple recommendation enhanced the request to federal authorities for steel girders needed to support military training in the new armory as this was a high priority.

In early 1918, less than a year after the United States entered the war, Cantwell told the Board of Agriculture that 600 current and former students from the college had already enlisted in the armed forces. The U.S. government and colleges across the country quickly realized that these enlistments were pulling many students out of college without the skills, trades and training that would be required by the military for successful completion of the war.

They would need engineers, architects, managers and mechanics to design and build bridges, run the supply logistics and repair the planes, trucks, tanks, automobiles, radios and other equipment of war. Keeping these men in college while beginning their military training became a top priority.

In February 1918, the United States Department of War established the Student Army Training Corps and “… announced its intention of establishing a military unit in every college that could furnish a minimum of 100 able-bodied men of military age.” Cantwell worked to insure that OAMC would become one of 525 institutions nationwide “to train draftees in a variety of trades needed for the war effort, and was jointly administered by the military and the college.”

In the spring of 1918, the War Department signed contracts with many of the colleges which had been established through the Morrill Act with the intent of creating technical training centers to utilize the expertise and equipment of their mechanical departments. Trainees in the Student Army Training Corps also received intensive military preparation under the direction of army officers provided to the institutions through the War Department.

OAMC passed the War Department’s inspection and male students were able to stay in college while beginning their non-officer military training. Men who did well with their academic classes and military exercises were transferred to the ROTC officer training program on campus. President Cantwell affirmed that all male students, except those who were unfit for military service, or who were below the draft age, were “required to enroll voluntarily” in the SATC on campus. They received the rank of private.

SATC training was scheduled to begin on July 18, 1918, and would last at least three months, however there were delays in its implementation. The college had to provide a new building with increased dining hall space and make a number of alterations to existing facilities before the first students turned-soldiers arrived in Stillwater. The military was to reimburse the institution for instruction costs, room and board, and other necessary expenses related to the training.

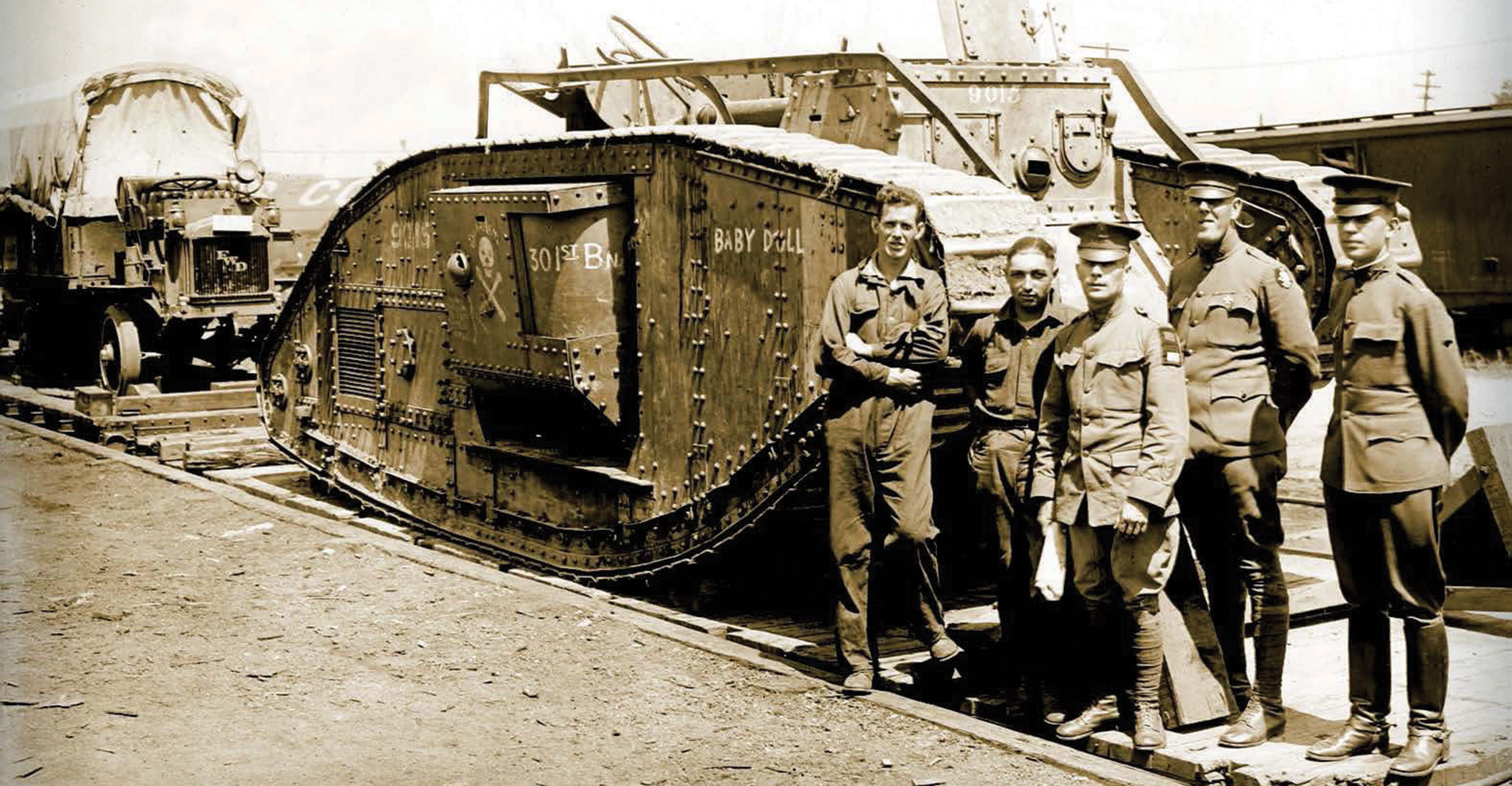

The men’s dormitory and remodeled livestock pavilion housed the 343 men enrolled in the 90-day program, which began September 1918. The Spanish Flu also arrived on campus that fall with the new recruits. When the war ended on Nov. 11, 1918, the federal government abandoned the plan as the first group approached completion. Cantwell took immediate action to arrange for the purchase at bargain prices of surplus army gas combustion engines, armored vehicles and additional machinery to help the School of Engineering broaden its areas of expertise.

The Great War in Europe was over, but its impact would be felt for generations. The war brought out the best and worst in humanity. There were 1,438 men and women associated with OAMC as students and employees who served in a variety of capacities during the war. Over 700 had been officers, 31 decorated for valor and 29 lost their lives. The college yearbook published in the spring of 1919 was titled Victory. It told some of their stories and honored their sacrifices. President Cantwell’s office reached out to many requesting information about their military service. Those replies are preserved and still available to the public at the OSU library archives. To learn more, visit archives.library.okstate.edu.

Photo by: OSU Archives

Story by: David C. Peters | STATE Magazine