Race Against Time: Kellington uses quick thinking to save a life on national television

Tuesday, September 5, 2023

Media Contact: Mack Burke | Associate Director of Media Relations | 405-744-5540 | editor@okstate.edu

Within 10 seconds, two lives were changed forever.

With 5:58 left in the first quarter of a Jan. 2 Monday Night Football game between the Buffalo Bills and Cincinnati Bengals, Damar Hamlin collapsed. It was 8:55 p.m. when the 24-year-old nearly died because of a rare cardiac event.

Time stopped.

At least it did for everyone watching around the world along with all the fans in the stadium and back home in southern Ohio and western New York.

But the clock had just begun for Denny Kellington and the Bills athletic training staff. It was something every athletic trainer in the NFL prepares for every week, no matter the unlikelihood of the event, as part of their emergency action planning.

In those 10 seconds, all those meetings, all the certifications and all the years of repetition after more than two decades in the profession proved crucial as Kellington provided CPR for the first time in his 27-year career.

The ensuing minutes of resuscitation and stabilization saved Hamlin’s life and forever altered Kellington’s.

Practice, Practice, Practice

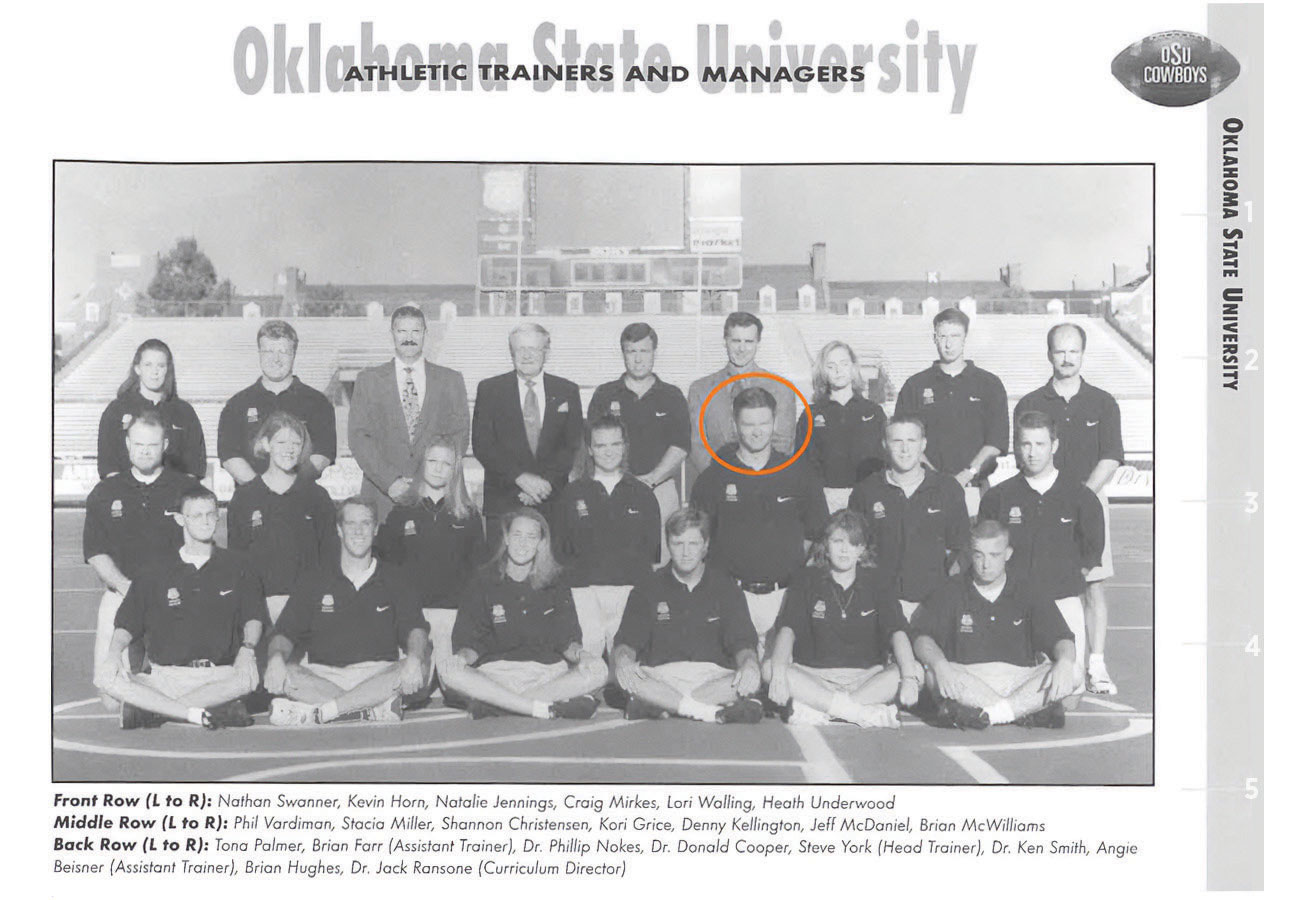

In 1996, two years before Hamlin was born, Kellington enrolled at Oklahoma State University to become an athletic trainer.

A Midwest City, Oklahoma, native, Kellington is the son of Denny G., who worked at General Motors, and Donna, a nurse. Denny grew up with his sister, Robyn, and brother, Tony, looking for ways to help people. It was the Kellington way. Denny G. and Tony both served in the military with Robyn later following in her mother’s footsteps as a nurse.

Kellington became inspired to be an athletic trainer after Don Fields and Dick Bobier, Midwest City High School athletic trainers, introduced him to the profession. Kellington, who played football, said it was something that sparked his interest.

What drew him to OSU was the chance to get on-the-job training while he was an undergraduate.

“That’s what athletic training is, it’s time on task,” Kellington said. “So, then the next four-and-a-half years was just getting as much experience with different sports, different injuries, different athletes, different coaching styles. All those are things that help you become a better athletic trainer.”

Kellington, who was a health and human performance major with an athletic training minor, came to Stillwater at the perfect time. Not only is hands-on training mostly reserved for graduate students nowadays, but when he came in the mid-1990s, it was only a few years after the program had even been established.

Dr. Marilyn Middlebrook, OSU associate athletic director of academic affairs, was part of a contingent of professors that wanted to start an athletic training program at the institution.

Eventually, the then College of Education, where Middlebrook taught, added the degree.

“So, Denny was a result of an initiative that the college didn’t think was going to be successful and ended up being unbelievably so. Much more so than they ever anticipated,” Middlebrook said.

Kellington was only required to work 1,500 hours as part of the program. He had that by the end of the first year and overall spent almost 10,000 hours in his four years working from sport to sport.

“There weren’t as many people around as there are now as far as working staff. So, we all had to work hand in hand to be the managers, athletic training students, GAs just working on the ground floor together,” said Matt Davis, OSU’s assistant director of facility operations and Kellington’s classmate.

One of the sports Kellington worked with was Cowboy wrestling. Legendary coach John Smith said Kellington made an impact as a student trainer.

“We rely so much on [athletic trainers], that sometimes they become another coach for us, trying to get them back on the mat and keeping their mind intact,” Smith said. “And I’ll just say that he did a hell of a job with our teams during that time.”

In December 2000, Kellington graduated from OSU, earning his first station as an intern for the Denver Broncos, starting a long association with the NFL.

Humble Beginnings

Ask anyone who has met Kellington and they will tell you he doesn’t heap much praise on himself.

He stands tall but likes to work in the background.

“He was always very kind of laid back and quiet, wasn’t boisterous, very unassuming. And man, I really enjoyed working with him,” Middlebrook said.

The ‘hero’ moniker he was later given following Hamlin’s full recovery never fit him, Kellington said. He was more excited about the national conversation around his actions using CPR and an automated external defibrillator on Hamlin and increasing the machines’ availability.

For him, his actions will always speak louder than his words. And for two decades with stops in Denver, with the Amsterdam Admirals of NFL Europe, at Ohio State University (where he earned his master’s degree), then Syracuse University and now the Bills, his actions did the talking.

He was known as an athletic trainer that both the players and coaches could trust, one who showed off his OSU pride by playing Garth Brooks in the locker room.

“I treat everybody equally and fairly with respect, and that’s where you earn trust from those individuals,” Kellington said. “If you don’t have trust, then you might as well go try something else. When we’re working with people, it is vital for their livelihood to trust you knowing that you’re doing everything you can to help them become better athletes or recover from an injury to get back to what they love.”

In fact, until that January night, he was practically unknown aside from his friends and family.

“Guys in our profession, it’s a thankless job,” Davis said. “You don’t look for pats on the back. You just do your job, you’re behind the scenes, the team behind the team.”

Scott Parker, OSU’s head football athletic trainer, crossed paths with Kellington when Parker was a graduate student at Syracuse right around the time Kellington started working there.

As the years went on, Kellington and Parker kept in touch, especially around the time of the draft if there was a chance of any OSU prospects coming to the Bills. Kellington and his wife, Jennifer, and two kids, Sydney and Bryton, came to Stillwater in 2022 — with Kellington even running into Davis at the Oklahoma City airport — and were given a tour of OSU’s facilities by Parker.

Little did he know, he would be returning to campus a little more than a year later … with much more fanfare.

Being Ready

Within 5 minutes of Hamlin collapsing on the field, an ambulance was on scene. In the coming hours, the nation would follow along with every update of his health and millions of dollars were donated to his charity.

On Thursday, Jan. 5, Hamlin woke up.

In the Bills’ next game, Hamlin watched from his hospital room as a storybook ending came to life. Buffalo running back Nyheim Hines returned two touchdowns, including the opening kickoff.

Hamlin has since made a full recovery, with doctors saying he could make a return to the NFL. His story has been forever connected with the man who was there 10 seconds after he collapsed, the person Hamlin would later say in an interview was the “savior of my life.”

Davis knew immediately Kellington was the one administering care to Hamlin, and tweeted out that he was an OSU graduate. Parker was notified by his parents and turned it on, seeing Kellington work through every athletic trainer’s worst nightmare. In fact, Parker had used an AED on an OSU player who suffered a cardiac event during a 2019 practice, and it was surreal seeing his fellow athletic trainer do the same on national TV.

“We’re not doctors and we’re not paramedics who do it on people multiple times a day,” Parker said. “Most athletic trainers don’t do it ever. I went through my training, thinking I probably would never do it on an athlete. … You’re just praying that everything goes well.”

Bills coach Sean McDermott later said in a news conference the athletic training staffs for both organizations and the city’s medical staff were all important in every role. But the most praise went to Buffalo’s assistant athletic trainer.

“For an assistant to find himself at that position and needing to take the action he did and take charge and step up,” McDermott said. “There were others on the field as well. It is nothing short of amazing and the courage that that took, you talk about a real leader, a real hero in saving Damar’s life.”

An Unexpected Door

While boarding a plane to be recognized at the Super Bowl, Kellington received a call with an offer he couldn’t refuse.

OSU Athletic Director Chad Weiberg was on the other end, inviting Kellington to be the spring commencement speaker at his alma mater.

“He wanted a little time to think about it,” Weiberg said. “Partly because he wanted to make sure the Bills organization was agreeable to it, as he would be back in rookie mini-camp by then. And partly because he just wanted to make sure he could do it right. I’ve learned, that’s just how Denny is.”

Parker mentioned that Kellington struggled with the attention early on but realized he could share the importance of CPR and AEDs with his unexpected platform.

“He called me one night, we talked for a while and kind of went over a lot of the different stuff that he’s kind of talked about in some of his interviews now about how they’re calling him a hero,” Parker said “He said, ‘Maybe I did a heroic effort, I guess. But it’s tough to be considered a hero. Hopefully this will be good exposure for the profession and for the need to care for these student-athletes.’”

After thinking OSU’s offer over, Kellington agreed to speak for the first time publicly since the event, inspiring graduates with his speech.

“I am genuinely grateful for the role that this university played in my personal path to success,” Kellington said in his commencement address. “But also, I’ve realized I’m now the experienced guy in the room, and I take my responsibility to share my knowledge with others seriously, hopefully, like a lot of older people did for me when I was the one sitting where you are.”

Kellington told students to trust in their experiences when facing the unexpected, just like he did on the night he saved Hamlin’s life.

“All the attention I’ve received for simply doing my job has been overwhelming. I’ve said repeatedly that I am not a hero, but I will tell you what I was that day, I was ready,” he said.

More than six months since that fateful evening, he still doesn’t know how much his life will continue to change. But if there is one thing Kellington is known for, it’s being prepared, because you never know how important something seemingly miniscule like 10 seconds might be.

“Understand this,” Kellington said. “Small things done with passion and intention have the potential to make a lasting impact with ripple effects that you may never understand.”

Photos by: Phil Shockley and Provided

Story by: Jordan Bishop | STATE Magazine