An original pioneer woman: The story of a forgotten work of art

Wednesday, May 8, 2024

Media Contact: Mack Burke | Associate Director of Media Relations | 405-744-5540 | editor@okstate.edu

“There are few men of the West of my generation who did not know of the pioneer woman in his own mother, and who does not rejoice to know that her part in building that great civilization is to have such beautiful recognition. It was those women who carried the refinement, the moral character and spiritual force into the West. Not only they bore great burdens of daily toil and the rearing of families, but they were intent that their children should have a chance, that doors of opportunity should be open to them. It was their insistence which made the schools and the churches.”

— President Herbert Hoover

(Ponca City Pioneer Woman Dedication, 1930)

For 95 years, Oklahoma State University has had a unique relationship with a pioneer woman who has resided with her infant on campus. Her name is Challenging, she is closely related to the pioneer woman statue in Ponca City, Oklahoma, and their births are linked directly to 10 others.

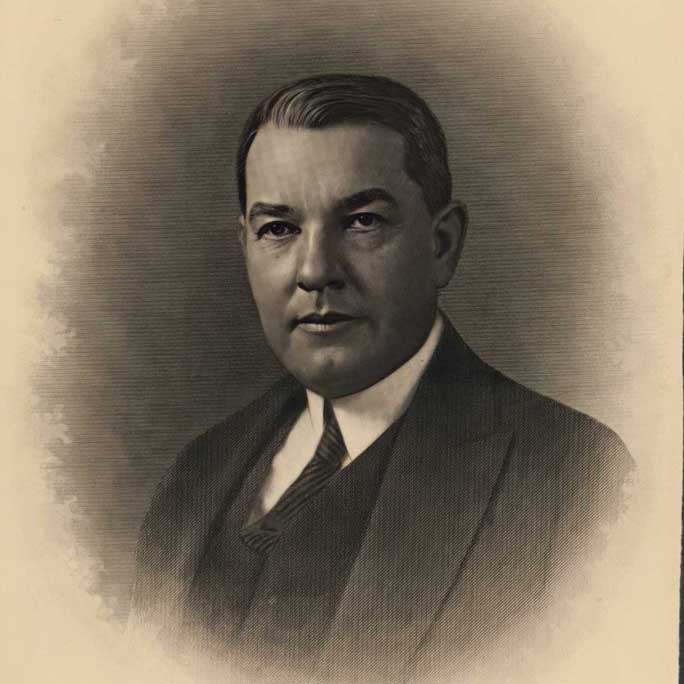

E.W. Marland, an Oklahoma governor, congressman and oilman, was also a philanthropist and supporter of the arts. Marland proposed a series of sculptures to document the settling of the American West, and in October 1926, he invited American and international sculptors to produce 3-foot models representing the best qualities of a pioneer woman.

Eventually 12 artists, all men, were selected and paid an honorarium to create unique individual bronze statuettes. By March 1927, a dozen sculptures were on display in New York City’s Reinhardt Galleries. Ninety-one-year-old Betty Wollman, whose family had settled in the Kansas Territory in 1855, attended the exhibit.

Interviewed by “The New York Times,” she said: “Mr. Marland is to be congratulated for doing this in commemoration of these early women of the West. The hardships were many, and the courage and self-denial of the women who worked side-by-side with their husbands and sons and brothers in those primitive days are largely responsible for the development of the Middle Western States, now so rich in everything that goes to make life worthwhile.”

After three weeks, the 12 statuettes traveled to Boston to begin a tour that included Buffalo, New York; Chicago; Cincinnati; Dallas; Detroit; Fort Worth, Texas; Indianapolis; Kansas City, Missouri; Minneapolis; St. Paul, Minnesota; Oklahoma City; Pittsburgh; Philadelphia; and finally, Ponca City.

Visitors at each site were asked to vote for their three favorites. With over 750,000 total attendees, more than 120,000 votes were cast. Marland made the ultimate decision and British-born Bryant Baker’s Pioneer Woman named Confident, which had received the most votes, was selected. Marland’s adopted son and nephew, George, made the announcement on Dec. 20, 1927, in New York City at the Reinhardt Galleries.

Some of the remaining models and recasts eventually found their way to Marland’s mansion in Ponca City. Later, all 12 went to Frank Phillips’ Woolaroc Museum near Bartlesville, Oklahoma, and others to cities and towns on the central plains, either in their original form, or as recasts or replicas. One statuette would find a home on the Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College campus in Stillwater a year before the Ponca City statue was dedicated.

A Challenging creation

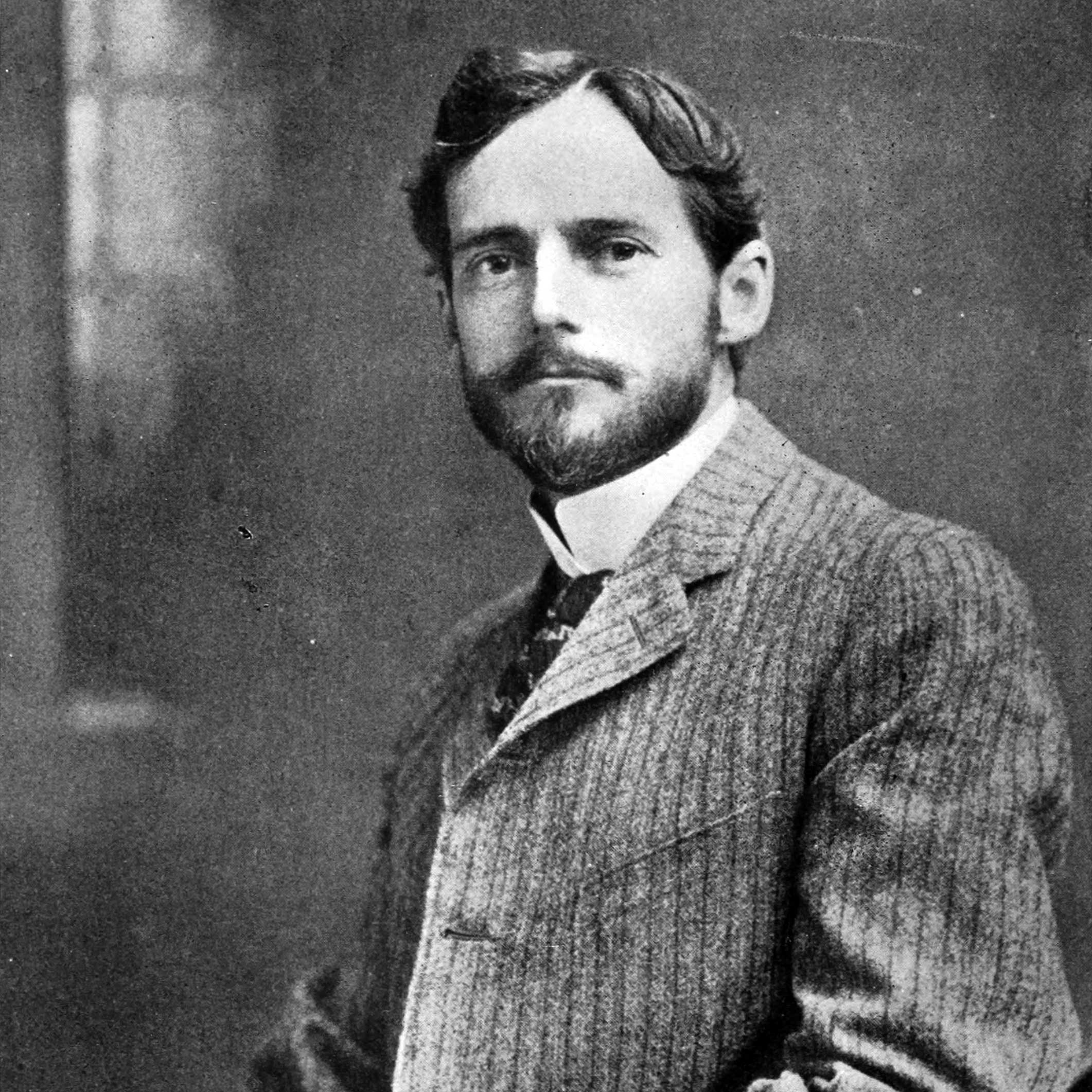

Hermon Atkins MacNeil was one of the artists invited to submit a statuette and receive the honorarium of $10,000, quite a sum of money in 1927.

Born in Everett, Massachusetts, in 1866, MacNeil was working in Paris when he heard of Marland’s project. MacNeil had spent considerable time studying art, architecture and design in Europe, living for extended periods in Paris and Rome. In his early 60s, he had developed an excellent reputation in the art world and was known especially for his sculptures.

MacNeil was probably best recognized for the Standing Liberty quarter (1916-30) and later in his career, for the East Pediment of the United States Supreme Court — Justice, the Guardian of Liberty — completed in 1934. During a career that spanned almost six decades, MacNeil produced over 200 sculptures with subjects including U.S. presidents George Washington, James Monroe, Abraham Lincoln and William McKinley; historical figures; statesmen; politicians; and Native American leaders. He also had cousins living in Stillwater.

During the summer of 1926, OAMC Dean of Home Economics Nora Talbot took a summer sabbatical and traveled to Europe on June 7 with her father’s first cousin, who happened to be MacNeil. They — along with MacNeil’s wife, Carol, also a wonderful artist, and their 15-year-old daughter, Joie — landed in Hamburg, Germany, and toured Germany, the Netherlands, France and England.

While in Paris, MacNeil wrote to an acquaintance on Sept. 12 about Marland’s pioneer woman statue proposal. MacNeil’s vision for the statue was of a strong mother in the western United States striding confidently into the future facing challenges with determination and courage. From his friend, he requested additional descriptions of female pioneers attempting to discover how she might appear and what she wore.

As inspiration, Marland provided sunbonnets, a common head covering worn by country women in the late 19th century frontier, to each of the artists. The women featured in nine of the statuettes contained sunbonnets in some way. Eleven of the 12 included a child.

In early 1927, MacNeil began production of a plaster model he called Survival of the Fittest. She was nude clutching an infant as she walked holding an axe in her right hand. On Feb. 26, 1927, he submitted his final statuette titled, Challenging.

MacNeil’s pioneer woman was cast in bronze at the American Art Foundry located in Queens, New York. He had draped his nude figure with appropriate western women’s period fashion, remaining barefoot and with a firm grip on the axe. His statue was part of the first group of seven models — that when joined with five others — would then tour the country with their pioneer sisters. MacNeil’s statuette received the second most votes in New York City and illustrations of Baker and MacNeil models were featured in an extensive article about the project appearing in “The New York Times.”

When all pioneer woman votes were tabulated at the end of the tour, MacNeil’s Challenging trailed only Baker’s Confident.

A gracious gift

For over 20 years, OAMC graduating classes had left memorials to the college. Some were utilitarian, such as a water fountain, a section of sidewalk, a fence, gates and a bench. Other donations were in remembrance such as the WWI service flag for those who had served in the war or a stone with 1905 carved on top placed near Old Central.

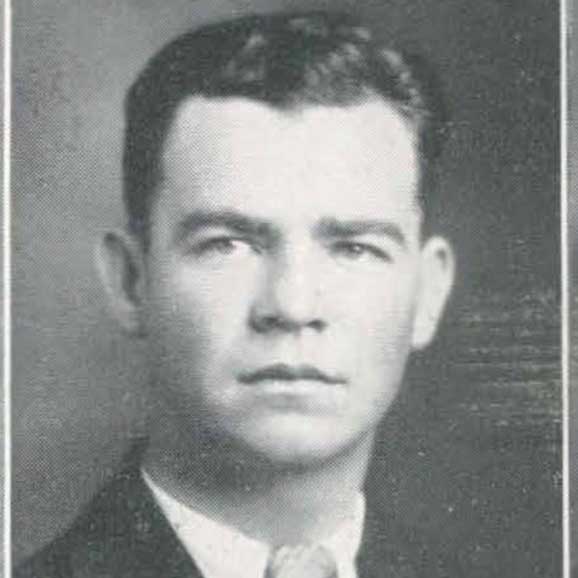

The OAMC Class of 1928 wanted to do something different and decided to leave a work of art, a statue. It may have been the first 3D art object purchased for the college. Daisy Dell McCool, instructor in drawing and art, suggested they consider MacNeil’s pioneer woman statuette. Class president Ted Frizzell took the idea to the seniors, and the class decided to approve the purchase.

McCool was acting head and instructor in drawing and art beginning in 1918 before taking a leave of absence during the 1923-24 school year. She traveled to England, France, Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands after surviving the campus administrative turmoil during the summer of 1923. Many OAMC staff and faculty had been fired or their contracts not renewed for the fall semester. Others had left in frustration and explored employment opportunities in higher education elsewhere. McCool took a sabbatical.

While in Europe, she may have had contact with MacNeil associates and Doel Reed. Reed was in Europe at the same time. McCool and Reed both returned to campus in 1924 with Reed taking over as head of the department and McCool serving as an assistant professor. Three earlier female instructors in the art department had been forced to resign after they married. McCool remained single and kept her job until 1931 when her position was eliminated during the first years of the Great Depression. She would eventually go to Hawaii and remain active in art and real estate until she passed away at 89.

The Class of 1928 planned to acquire an exact replica of the MacNeil pioneer woman bronze. The statuette they purchased was produced at the American Art Foundry in 1928 and placed on display at New York City’s National Sculpture Exhibition from Oct. 1 through Dec. 16, 1928. MacNeil was a member of the National Sculpture Society and had been selected to the American Academy of Art and Letters the previous year. The 3-foot statuette was anticipated to be shipped later in December after the close of the exhibition and arrived in Stillwater around Jan. 1, 1929. Arrangements were made for a special pedestal to be placed in the college library, which was designated to become her final residence.

The formal dedication of the 17-foot-tall pioneer woman statue in Ponca City would take place on April 22, 1930, with over 40,000 in attendance. U.S. President Herbert Hoover addressed the crowd from the White House and Will Rogers flew in from California.

But, with this project and other lifestyle expenditures, Marland had overextended his finances. Marland Oil Company would fall into bankruptcy in the early 1930s and Marland would turn to politics where he served in the U.S. Congress from 1933-35 when he was elected Oklahoma governor and served in that role until January 1939. He would die on Oct. 3, 1941, nearly bankrupt and only 67.

A forgotten figure

MacNeil visited the Talbot family and OAMC in the spring of 1940.

He was invited to the art department to talk with students and met on campus with Reed, having first seen him in 1927 while both men were in Paris. MacNeil had come to the Midwest for the dedication of his statue, The Pony Express, located in St. Joseph, Missouri, and then returned to his studio and winter home located in Pinebluff, North Carolina.

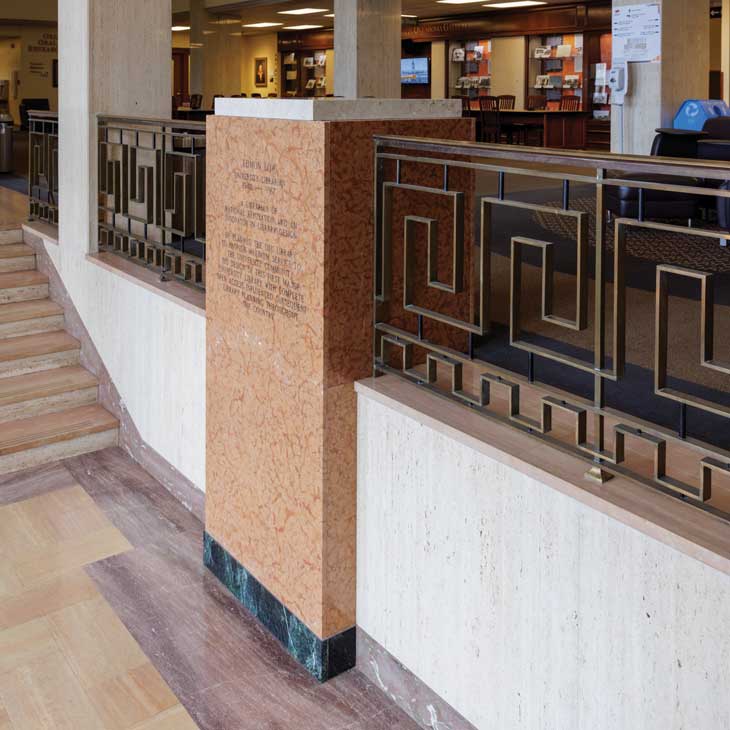

The installation of OAMC’s 3-foot pioneer woman statuette in the college library occurred sometime in the spring of 1929. She would reside there for over 20 years until “temporarily” moved to the Student Union in 1952 while waiting for Edmon Low Library to be completed a year later.

During the transition of materials from the old college library to the new facility in 1953, she remained at the Student Union. A pedestal had been placed at the top of the second-floor front landing in the new library to support and display the pioneer woman statue.

With the death of OAMC President Henry Bennett in December 1951 and the many other challenges occurring on campus in the early 1950s, the final transfer of MacNeil’s pioneer woman statue to her permanent home in the new library was never completed and she resides to this day in the OSU Student Union.

Photos by: OSU Archives

Story by: David C. Peters | STATE Magazine