Brain Matters: OSU-CHS researchers studying semaglutide for possible addiction treatment

Wednesday, May 8, 2024

Media Contact: Mack Burke | Associate Director of Media Relations | 405-744-5540 | editor@okstate.edu

Many have seen semaglutide advertised or heard it talked about on TV and radio. You may know it by some of its other names like Ozempic, Wegovy or Rybelsus.

Originally designed to treat type 2 diabetes and obesity, the medication is also being studied as a possible treatment for many other conditions and diseases, including addiction.

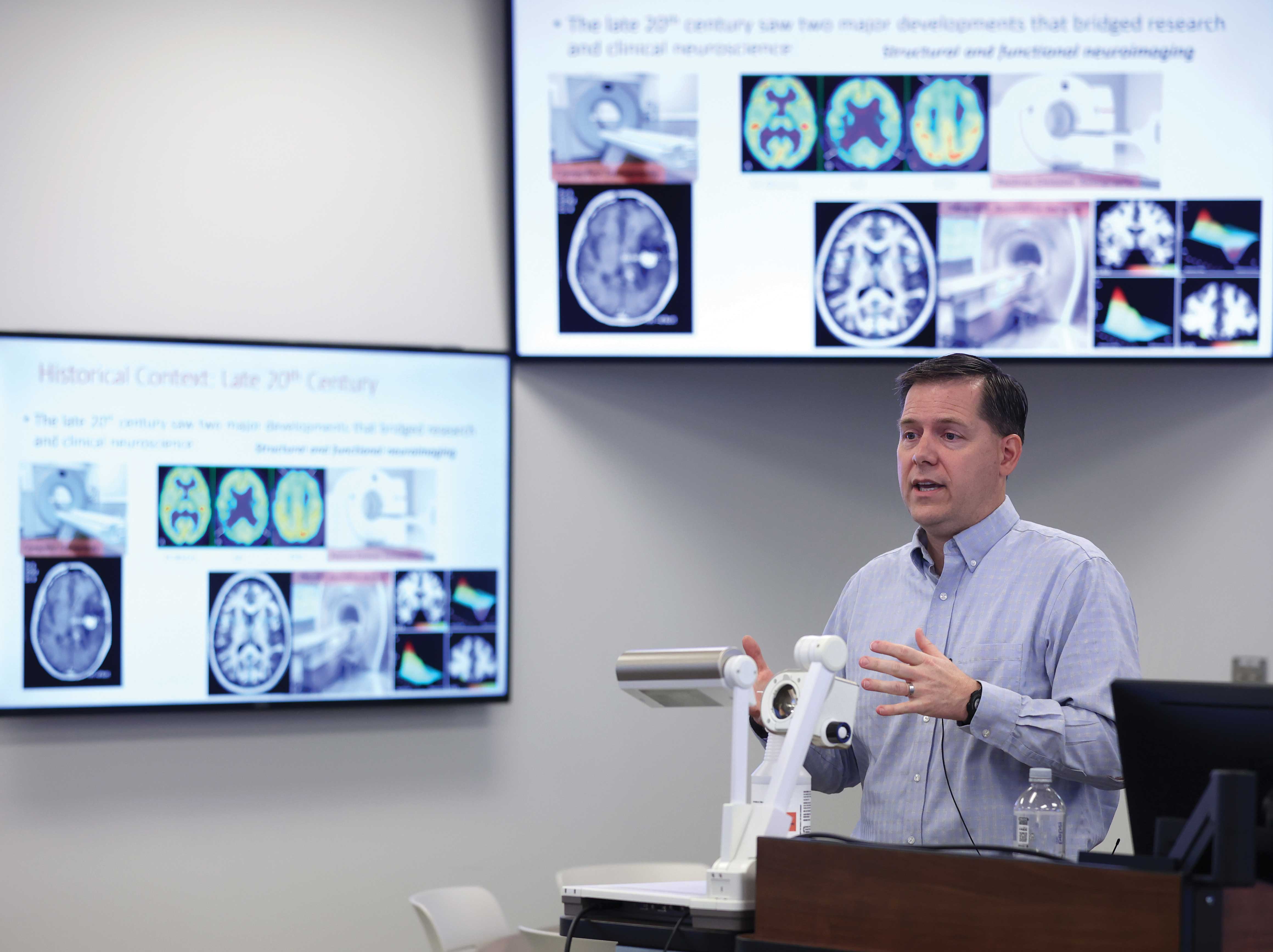

Dr. W. Kyle Simmons — Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences professor of pharmacology and physiology — is leading the Semaglutide Therapy for Alcohol Reduction study at OSU’s Hardesty Center for Clinical Research and Neuroscience to determine whether semaglutide can be used to treat alcohol use disorder.

Simmons has a personal connection to the STAR study and its findings. His grandfather battled alcohol use disorder for most of his life.

“He eventually achieved a measure of sobriety and started a business in the 1950s and ’60s that produced items like sobriety chips and coins for organizations like Alcoholics Anonymous,” he said.

Simmons even worked there himself when he was younger filling orders, stocking shelves and attending sobriety conventions as a vendor.

“It gave me a real-world, personal connection to this group of people who are struggling with this disease,” he said. “At a young age, I saw that recovery is possible. It definitely motivates me.”

How does it work?

Semaglutide is a molecule that mimics the natural hormone GLP-1, which is released right after eating, and signals the brain that we no longer need food.

“Our natural GLP-1 only lasts about 10 minutes, which is why you can feel full after eating a large meal, but still be able to eat a dessert if you wait 10 to 15 minutes” said Dr. Stacy Chronister, OSU-CHS clinical assistant professor of internal medicine and board-certified physician in obesity medicine.

Semaglutide is nearly identical to GLP-1 with only three small molecules changed so it remains active in the body for a week rather than just minutes, Chronister said, decreasing a person’s food intake because they feel fuller more quickly and for longer.

"At a young age, I saw that recovery is possible. It definitely motivates me."

“Less food means less glucose in the bloodstream, which improves diabetic symptoms and outcomes. For the disease of obesity, the patient loses weight because of the effects of decreased food intake but has the added benefit of the GLP-1 working on the weight loss receptors in the brain,” she said.

Dr. Kelly Murray — OSU-CHS professor of clinical pharmacy — said GLP-1 is also responsible for telling the body when to release insulin that helps cells use sugars in your blood for energy, which in turn decreases blood sugar in diabetic patients.

Simmons said the way semaglutide works to reduce hunger and the desire for food could potentially decrease the desire for substances like alcohol.

“Semaglutide binds to receptors in the brain involved in dopamine signaling,” he said. “These regions in the brain play a significant role in making us want and enjoy things that make us feel good. They are critical for motivating us to seek out and enjoy rewarding experiences.”

Bright STAR

Late last year, Simmons and another researcher from the University of Oklahoma/University of Tulsa School of Community Medicine co-authored a paper published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry that found six patients who received semaglutide for weight loss also demonstrated a significant decrease in their Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test scores.

Now, Simmons is leading the largerscale STAR study — a double-blind, placebo controlled clinical trial — that involves thorough screening and a range of evaluations including neuroimaging at the Hardesty Center for Clinical Research and Neuroscience, where he also serves as director of the OSU Biomedical Imaging Center.

“This means that neither the participants nor the researchers interacting with them know whether the participant is receiving the actual medication, semaglutide, or a placebo,” he said. “This design helps ensure the results are not influenced by biases and that any observed effects are genuinely linked to the medication.”

Participants in the STAR study are screened and baseline measurements and neuroimaging scans are recorded before receiving either semaglutide or a placebo for 12 weeks. Records of any changes in behavior, brain activity and biomarkers are examined during the study period and at the end of 12 weeks.

“The focus is not only on changes in their drinking behavior, but also how their brain activity and various bodily systems — endocrine, metabolic and immune pathways — may be linked to these changes,” Simmons said.

The study is also looking at semaglutide’s potential effects on other rewarding behaviors.

“There’s a concern that semaglutide might not only reduce the desire for harmful substances like alcohol, but also affect other rewarding behaviors, potentially leading to anhedonia, a loss of interest in pleasure,” he said. “It’s extremely important that we figure that out because that helps us understand who this medication would be safe for and who it wouldn’t.”

The STAR study will continue into 2025. Simmons and his team are still enrolling people for the study.

“For those who believe they might be candidates for the study and are experiencing a relatively high level of weekly alcohol consumption, I would encourage them to reach out and complete the online screener to see if they qualify for the study,” he said.

He strongly discourages people from seeking out semaglutide on their own as a treatment.

“This is a clinical trial to discover whether semaglutide is safe and effective in humans for alcohol use disorder treatment. We don’t know if it is,” he said. “If patients are struggling with alcohol use disorder and they want treatment for it, there are good options available, and they should reach out to their care provider to access those treatments.”

A healthier Oklahoma

Right now, semaglutide is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat type 2 diabetes and for weight management. And if Simmons’ STAR study and other studies like it across the country are successful, it may also be approved to treat alcohol use disorder and other addictions in a few years, potentially impacting the health of thousands of Oklahomans.

Nearly half of Oklahoma adults have either diabetes or prediabetes according to the American Diabetes Association. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that Oklahoma has the third highest prevalence of obesity in the nation, affecting about 40% of its population.

And about 16% of Oklahomans report a substance use disorder, but only a fraction are receiving treatment.

“The costs of each of these three diagnoses are profound, and each carries risks of additional downstream health consequences if not appropriately treated,” Murray said. “Diabetes, obesity and substance use disorder diagnoses don’t happen in silos. Many Oklahomans suffer from two or maybe even all three.”

Chronister said diabetes, obesity and substance use disorder cost the state about $5 billion in health care costs a year, but that doesn’t give the full picture.

“These conditions result in lost time from work, higher disability rates, increases in mental health conditions and, most importantly, the inability to live the active lives that we want to lead,” she said, so the potential for one medication to treat multiple conditions could be revolutionary.

“Food and addictive substances use the same receptors to tell our bodies that ‘this is good for us’ and ‘this makes me feel better.’ We already have medications that are used for both obesity and in the treatment of addiction, so it’s only natural that we look to see if that link exists with semaglutide as well. There are also ongoing studies for the use of semaglutide in osteoarthritis, depression and even Alzheimer’s disease.”

Murray said she is also excited about the potential impact semaglutide could have on the overall health of Oklahomans.

“Health care teams do their best to treat patients as a whole. If there’s a medication with the ability to help treat multiple conditions, this could lower a patient’s exposure to multiple medications in turn decreasing the risks of side effects and drug interactions, and potentially lowering health care costs to patients as well as the health care system,” she said.

Still, it’s important for people to always consult their doctor or medical providers before starting a new medication or treatment. Side effects of semaglutide are usually gastrointestinal with nausea and vomiting being the most common.

“Semaglutide can benefit many Oklahomans, but it’s incredibly important to talk to your health care team to determine if it is right for you,” Murray said. “Just like with any medication, ask for guidance on how to administer it, what side effects to expect and if you need to adjust how you take any other medications you’re prescribed. And make sure to follow up with your health care team to monitor how the medication is working.”

Photos by: Matt Barnard and courtesy of OSU Biomedical Imaging Center

Story by: Sara Plummer | STATE Magazine