What's hopping in Oklahoma: Doctoral student combines passion for craft beverages with hops research

Friday, December 13, 2024

Media Contact: Sophia Fahleson | Digital Communications Specialist | 405-744-7063 | sophia.fahleson@okstate.edu

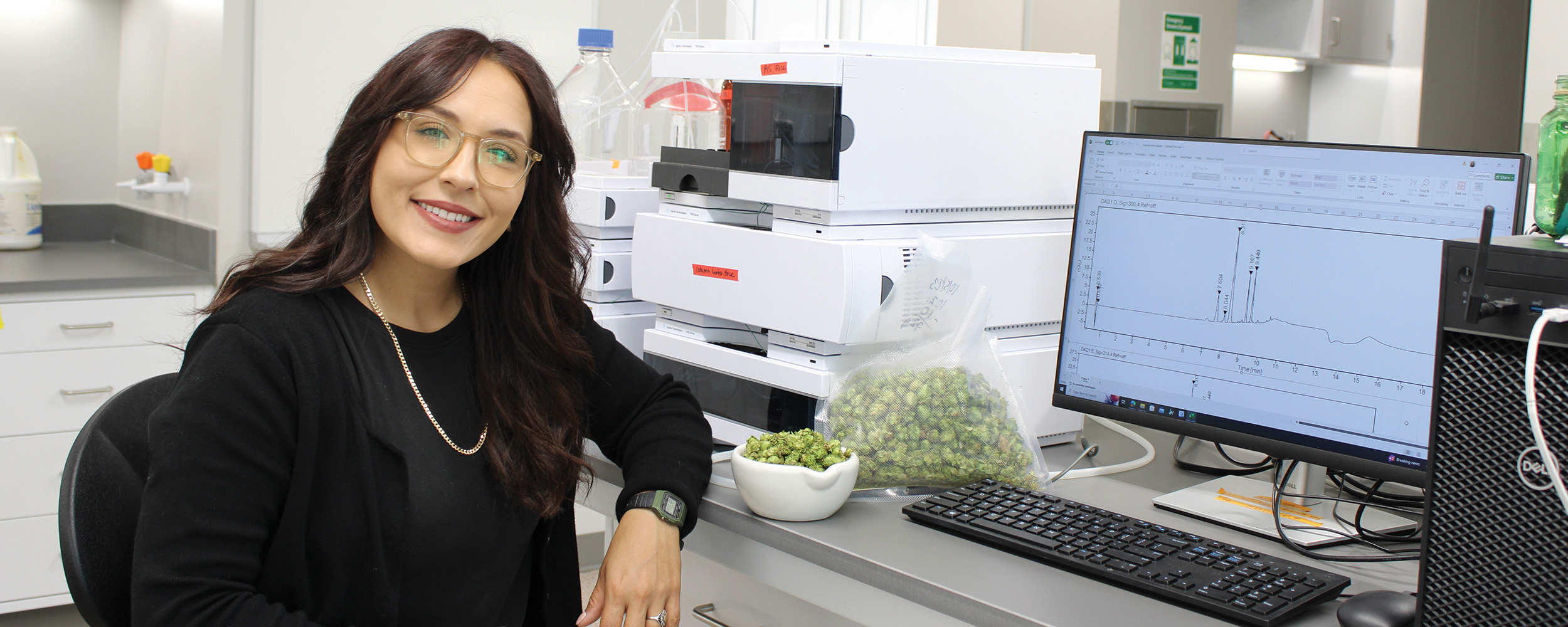

With little knowledge of the agricultural industry, Katie Stenmark moved from a small town in North Carolina to Stillwater, Oklahoma. Now, she is opening doors by researching hops as an emerging crop.

“It was my senior year of high school when I saw a plant diagram for the first time,” said Stenmark, third-year crop science doctoral student.

Stenmark pursued an undergraduate degree at Oklahoma State University in horticulture with a minor in pest management. Working with wine grapes at the Cimarron Valley Research Station in Perkins, Oklahoma, during her undergraduate studies gave her a glimpse into the world of trellised crops and sparked her interest in research, she said.

“During my master’s degree at OSU, we were working with eastern red cedar, and that’s when I moved into the lab area and learned how to work around the lab and to use different types of equipment,” Stenmark said.

Although hops are not typically grown in Oklahoma, these experiences laid the groundwork for conducting research about growing hops in Oklahoma, Stenmark said. Stenmark combined a passion for lab work and the agricultural side of craft brewing when she decided to pursue a doctorate, she said.

“Katie has an interest in craft beer and hops, which is a great tie-in for her,” said Niels Maness, horticulture and landscape architecture professor. “It’s not often you get a project the person has that natural connection to.”

Humulus lupulus, or hops, are part of the Cannabaceae family. They grow differently than many other crops, Maness said. Using a trellis system, the plants create a canopy on the top of the structure, he added.

“About 98% of commercial production of hops is in Washington, Idaho and Oregon,” said Charles Fontanier, associate professor of horticulture and landscape architecture. “Growing hops in Oklahoma would not be a logical first choice.”

To further understand what types of hops Oklahoma brewers prefer, surveys were conducted before hop were planted. This gives researchers a better understanding of the quantity of hops they use and if they would be interested in purchasing locally sourced hops, Stenmark said.

Based on the survey answers, nine hop varieties stood out for what Oklahoma brewers would prefer. Each of the varieties has a unique flavor profile, said Fontanier, who is Stenmark’s academic adviser. When one variety died, the researchers replaced it with a different variety.

“The local initiative has gotten intertwined into any kind of agricultural product,” Stenmark said. “We got some answers from local brewers that helped us decide on what kind of plants we should purchase because we were starting from ground zero here — from no plants into having a hop yard.”

The hop yard is located at the Cimarron Valley Research Station.

With any crop being planted, researchers look at all the essential things: how the crop will grow in Oklahoma, what is the expected yield, and what quality can be produced, Stenmark said.

As the hops are harvested, the quality is tested, and at this point, the brewing industry and research become intertwined, Stenmark said.

The acids and oils in hops give brewed beverages their unique flavor and aroma, she added.

“We are looking for what makes a beverage bitter, or the alpha and beta acids,” Maness said. “We measure this by HPLC. An HPLC analysis is high-performance liquid chromatography, which is separating and identifying liquid samples.”

Researchers are testing the quality of the hops, Stenmark said. As part of her dissertation, Stenmark plans to work with the Robert M. Kerr Food and Agricultural Products Center to conduct sensory analysis on Oklahoma hops, she added.

A sensory analysis is a way to understand how the different hops taste and smell as well as to understand how the hops can be used in brewing, Stenmark said.

Another step is developing a hop flavor wheel, which will help brewers understand if Oklahoma-grown hops have a unique taste and aroma, which could be from varying environmental factors, she added.

“We can grow the same types of hops another region grows, and it is going to produce different sensory attributes,” Stenmark said.

Conducting trials in Oklahoma has the potential to help not only Oklahoma agriculture but also hop producers throughout the country, Fontanier said.

“As we look at areas like the Pacific Northwest, they’re being impacted by climate change and population growth,” Fontanier said. “They’re also getting hit with temperatures and droughts they historically didn’t have.

“However, we are trying to improve the genetics of these plants in the future,” he added.

Having the ability to have drought-tolerant crops is important in Oklahoma, Stenmark said, which is true for hops, as well. Researchers look at the yield potential because sufficient yields will help justify having hops and promoting the crop to interested Oklahoma-based producers, she added.

The disease resistance aspect of this research also is important, Stenmark said.

Oklahoma’s heat and humidity create a suitable environment for more pests and diseases compared to traditional hop-growing areas in higher altitudes, Stenmark said. Researchers must understand the potential interaction of pests and diseases with these plants, she added.

This project brings the potential for more specialty brews to be made in the state, Maness said. The most notable is wet hopping, he added.

“Wet hopping uses fresh hops added to the beer,” Maness said. “After the boiling process is complete, the wet hops add flavor and a little bit of bittering potential.”

Oklahoma hops are more achievable as wet hops. However, dry hops become more of a commodity with their life and exporting potential being extended, Fontanier said.

Dried hops can be used for various products: beers, non-alcoholic beers, tea, personal care products and hop water, he added.

“We’re looking at hops as a new crop for Oklahoma,” Maness said, “not just a hobby, but something producers can raise to make a living or subsidize a living with.”

Oklahoma has three of the four ingredients to make craft beer: water, grain and yeast. Hops are the only missing piece of the equation, Stenmark said.

Story by Makayla Craig | Cowboy Journal