"I Keep Going"

Monday, October 15, 2018

Despite an extremely challenging year for educators across the state of Oklahoma, Sarah Kirk continues to put her students’ needs first. Within their youthful eyes, she finds the motivation and inspiration to move forward.

“I just look at them, and I keep going,” said Kirk, a two-time Oklahoma State University graduate and current school counselor at Monroe Elementary School in Norman, Oklahoma.

Kirk has been at Monroe since earning her master’s in counseling from the OSU College of Education, Health and Aviation in 2012. She hit the ground running there, and her efforts have not gone unnoticed. In May, Kirk was named as the Oklahoma School Counselor of the Year for 2018- 19 by the Oklahoma School Counselor Association.

However, the honor came on the cusp of what Kirk describes as the worst week of her career — the teacher walkout.

“It was tough,” she recalled. “There was a lot of heartache out there. The hardest part was feeling like these people [legislators] weren’t making choices that were best for our kids, and that’s tough because as an educator, we make thousands of decisions every single day and every one of those is based on what’s best for our kids.”

That resolve has driven Kirk to be more collaborative and innovative as she advocates for students.

Team Effort

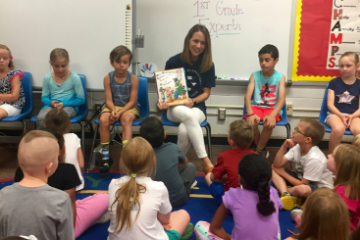

The life of a school counselor is extremely diverse; no two days are ever the same. Primarily, counselors focus on students' social, emotional, academic and career development. They also provide responsive services to students, such as crisis or behavioral intervention; connecting families to community resources; and offering classroom guidance. Their role is pivotal to student development.

Shortly after arriving at Monroe Elementary, Kirk realized it was going to take more than the efforts of one counselor to meet the intensive needs of her 480 students, a student-to-counselor ratio nearly double the recommended 250 to 1 by the National School Counselor Association. Kirk had big dreams, and she knew that creating a culture of shared responsibility and implementing comprehensive programming would be crucial to achieving her goals.

“My principal and I have worked over the last six to seven years to create a climate in our school where the more traditional role of guidance counselor is assumed by every adult in our building, so that collectively we are teaching our kids about respect, cooperation and excellence,” Kirk said. “We’ve worked hard to create supports, interventions and programming beyond what just a single person can do.”

Responding to the Need

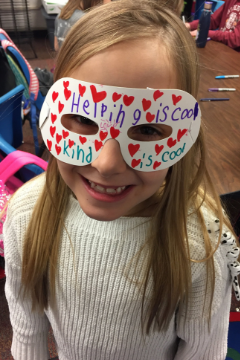

“What do our students need? What’s missing?” Kirk and her team ask those questions on a regular basis. The answers would have a profound impact on Monroe students as well as students across Oklahoma when Kirk introduced the Great Kindness challenge to her school, and the state, in 2014. Kirk adopted the initiative from a group of California parents who recognized the same need in their schools.

The weeklong celebration to empower students to create a culture of kindness met an overwhelmingly positive response from teachers, students and parents. Whether completing acts of kindness, sharing stories or participating in encouraging activities, the students connected with the concept, and it soon became more than just a week.

“The whole culture of our school changed because we were including kindness in everything we did,” Kirk said.

Monroe’s success with the program led to Kirk being asked to be a Great Kindness Challenge state ambassador and introduce the program to hundreds of other schools in Oklahoma. What initially began as a small grassroots effort in California now includes nearly 20,000 schools, reaching over 10 million students in over 100 countries.

One week of kindness just wasn’t enough: In 2015, Kirk assembled the Monroe Elementary Kindness Ambassadors, a group of students who meet after school to promote kindness in their classrooms on a regular basis. After its first year, the group grew from 30 to 150 students. One notable project that has come out of the group is the buddy bench. The Kindness Ambassadors raised money to build a special bench on the playground, intentionally designed as a place for students to sit if they need a friend to play with or someone to talk to.

“The concept is positive and not punitive; it’s teaching kids what to do, as opposed to what not to do,” Kirk emphasized.

She went on to build a mentor program for students with more intensive needs. She saw that many of her students did not have a healthy adult role model in their life. With the help of a local church group, Kirk paired 25 students with 25 selected adult mentors. The mentors provide stability, support and encouragement to students by instilling the importance of making good decisions and helping them achieve their goals.

The Time is Now

As Kirk and her team continue to look for new ways to meet students’ needs, the funding to support programs and positions remains a primary cause for concern, especially for school counselors whose positions are among the first to be cut when budget crises arise.

“The number one question I get asked is, why does an elementary school need a counselor?” Kirk said. “On a very frequent basis, I’m dealing with students who suffer from depression and anxiety, self-harm, suicidal ideation and violence. These are real issues we are dealing with. I can’t imagine there not being someone in these schools to support these students and connect them to the resources and help they need.”

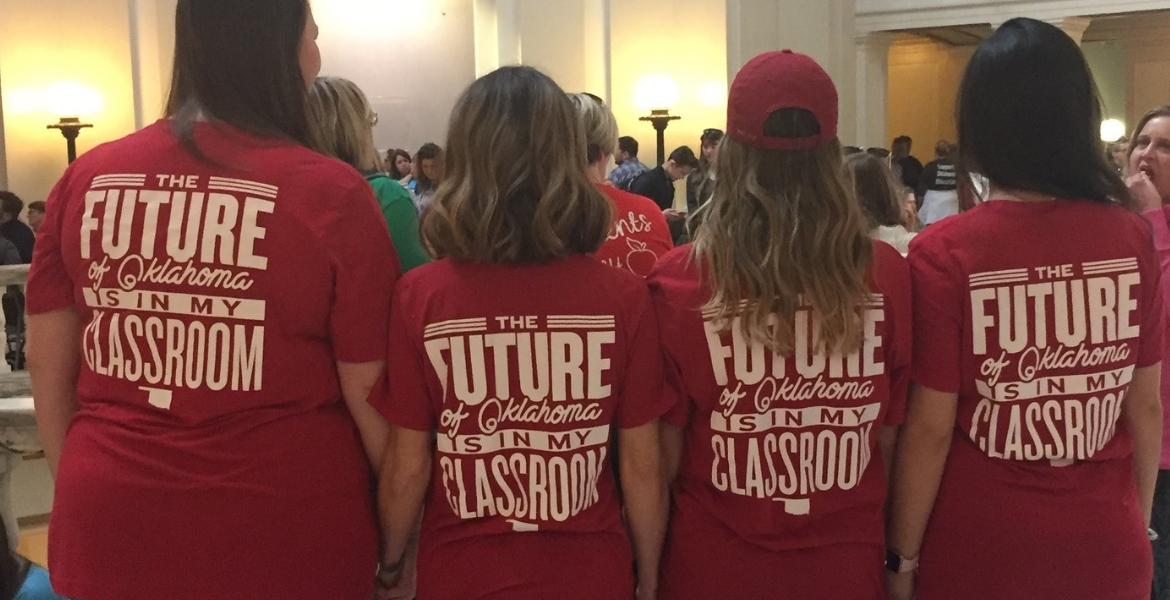

The drive to do what’s best for her kids led Kirk and nearly 40,000 educators across Oklahoma to walk out of the classroom on April 2. Their message was clear: Oklahoma must find a way to fund public education and ensure students a brighter future.

For nine days, teachers, students, parents and residents gathered at the state Capitol to advocate for public education.

“It was powerful to see that,” she said.

The days were long and frustrations were high as thousands of educators sought answers. However, after nearly two weeks, the walkout came to an end when it was clear the Legislature would not make a significant movement toward solving the funding issues.

“I wish it had resulted differently,” Kirk reflected. “It was tough to know we were going to come back to 480 faces and say, ‘We tried really hard, but we didn’t win.’ It felt defeating for sure. But at the same time, it was neat to see thousands of educators coming together for what they thought was right.”

The movement didn’t end once class was back in session. The conversation continued, and educators remained steadfast in their quest to be heard. Civic engagement would become the new platform for change as educators across the state exercised their right to vote and chose to be active participants in Oklahoma’s legislative processes.

According to the state election board, voter turnout for Oklahoma’s June primary election surpassed the turnout for the 2014 general election and the 2016 presidential primary election.

“The walkout has forced people to face what’s happening in public education,” Kirk said. “It has forced people to see that we have to make a change. There’s no other option at this point. We are losing amazing educators.”

The Big Picture

Kirk became a counselor because she knew the impact she could have on students. That’s also the reason she stays.

“The level of respect for the job may have decreased and the salary may not have increased, but the need is still there,” she said. “I want young people who are considering education as a profession to see they are so needed and they can make a huge difference.”

Making a difference is what drives the OSU College of Education, Health and Aviation to continue to prepare educators like Kirk, who are equipped and committed to improving the lives of students by dreaming big.

“I want to grow my reach,” Kirk emphasized. “I don’t know what that looks like exactly, but I have a desire to get other people doing what I’m doing. I want to educate others on how they can most effectively impact their school. I want all of our kids to receive the services and support they need.”