Service and Sacrifice: Casualties, courage and faith during the Great War

Tuesday, December 20, 2022

Media Contact: Mack Burke | Associate Director of Media Relations | 405-744-5540 | editor@okstate.edu

Editor’s note: This article is the final part in a series about life at OSU leading up to and during World War I. See parts one and two in the spring and fall 2022 issues of STATE.

The Great War ended suddenly.

After four years of conflict abroad and dramatic changes on the Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College campus, which included adjusting operations to provide trained personnel for the conflict in Europe, it was over.

In the 11th hour on the 11th day in the 11th month of 1918, fighting in the Great War ceased. The casualties on all sides were enormous and devastating. The exact number of deaths is unknown, but 11 million military service members and six to 12 million civilians were estimated dead. Additionally, over 20 million suffered wounds, the most critical of which became life-altering.

Empires had crumbled, but little else had been accomplished.

It took weeks, sometimes months, for families living in Oklahoma to receive word on the status of their loved ones in Europe. Most soldiers training stateside were released from military service and returned home quickly. For those in Europe, it took much longer. OAMC maintained records for its students and staff in military service and updated these lists as new information became available. There were attempts to document the college’s participation in the war and recognize the individuals who served in the war effort.

Remembering military service “of any kind” and the sacrifices of service men and women affiliated with the college was a top priority in the spring of 1919.

Days after the war’s conclusion, OAMC President James W. Cantwell sent a questionnaire to all known participants requesting information about their “personal story.” The letter was cosigned by yearbook editor Maude Cass, librarian Margaret Walters and history professor Samuel A. Maroney. The responses were to be bound and preserved in the library and information shared in the 1919 yearbook, which would be titled “Victory.”

The college database of soldiers included names for 1,438 individuals, including two women who served in the medical corps, Ethel Boydstein and Elsie Wiggs. Twenty-nine lost their lives — 12 from combat wounds, 12 from disease, two from drowning, and three from unknown causes. Ten of the 12 combat deaths occurred in the last month of the war. Cpl. Joseph P. Mitchell died only five days before the cease-fire. Hundreds were wounded but survived.

The Girls Student Association was instrumental in creating two service flags of honor acknowledging those who served in the war with individual stars. They were shared at special occasions across the state, and stored in a locked vault for protection and disappeared.

The personal stories of those involved in the war varied greatly. The responses to the college’s questionnaire included experiences of gallantry, fear, suffering, boredom and humor. Many included pictures documenting their experiences. There were over 500 responses, but space only allows for four stories to be shared here.

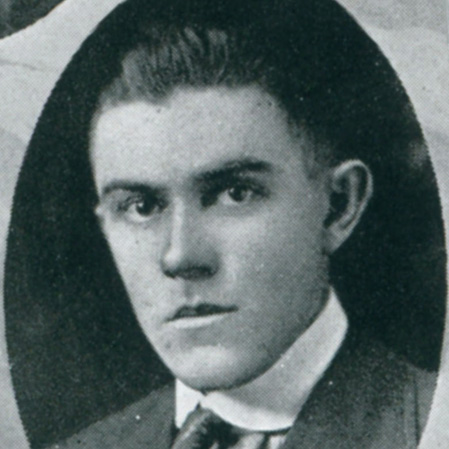

Raymond Thomas Hurst

Hurst, an OAMC student from Pocasset, Oklahoma, enlisted on Oct. 3, 1917. He was a private in the First Engineering Corps serving as a bugler. In February 1918, Hurst was on board the steamship Tuscania with over 2,000 American soldiers being transported to England as part of a British convoy. A German submarine sent a torpedo into the Tuscania on Feb. 5 when it was sailing near the coastal islands between Ireland and Scotland.

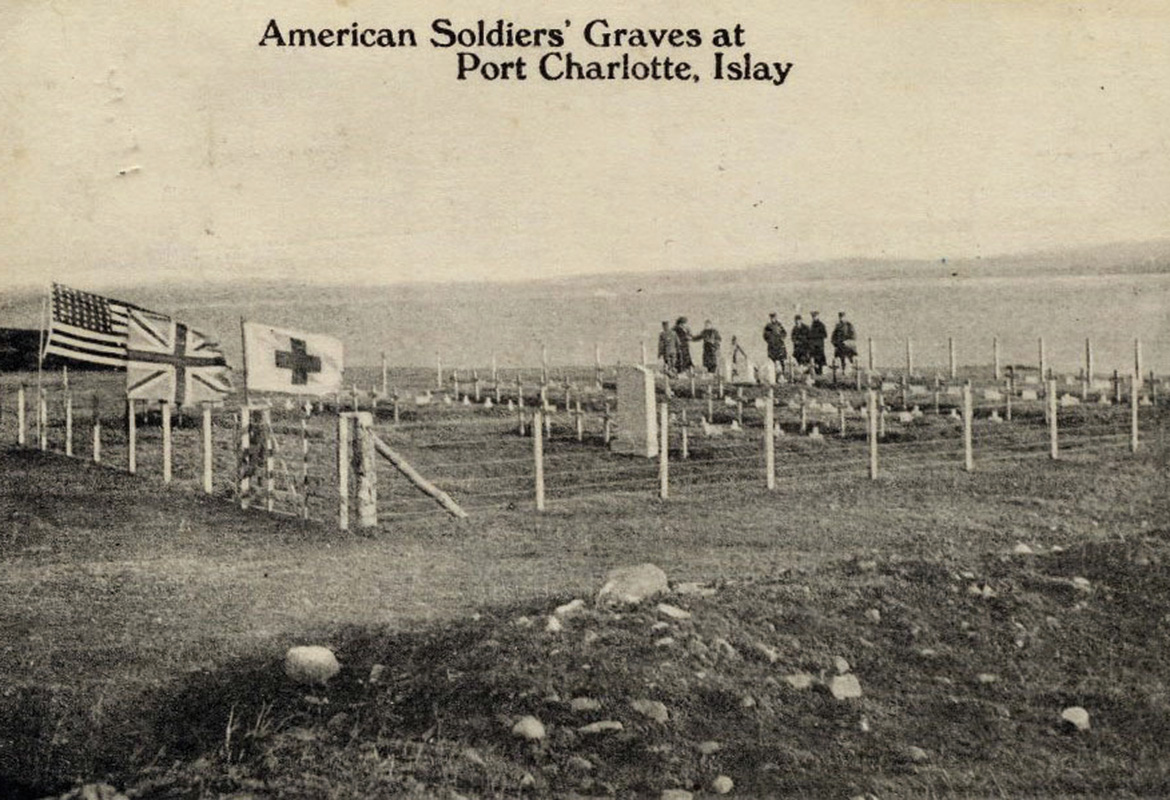

The ship didn’t sink immediately and the majority of its passengers were rescued, however 210 people either died from the initial explosion or drowning. Hurst’s body was found along the Scotland coast. He was buried at Port Charlotte in a small cemetery created for the victims. It took 10 days for the news of his death to reach Stillwater. Two years later, his remains were moved to Oklahoma City, and Hurst was buried with full military honors. Hurst was the first “combat” victim with ties to Oklahoma A&M.

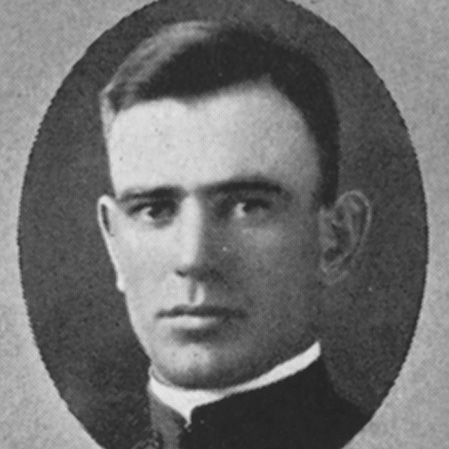

George Price Hays

Hays was born in China where his parents served as missionaries. After completing their mission tour, the Hays family moved to a farm between El Reno and Okarche, Oklahoma, where Hays grew up before enrolling in the engineering school at Oklahoma A&M.

Hays was commissioned as a second lieutenant in 1917 and by July 14, 1918, he was a first lieutenant serving with the 10th Field Artillery Regiment, 3rd Division. The Second Battle of the Marne began late on July 14 with a German advance across the Marne River, roughly 50 miles east of Paris. The records from the official General Order No. 34 (March 7, 1919), War Department state:

“The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to First Lieutenant (Field Artillery) George Price Hays, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on July 14 & 15, 1918, while serving with the 10th Field Artillery, 3d Division, in action at Greves Farm, France. At the very outset of the unprecedented artillery bombardment by the enemy, First Lieutenant Hays’ lines of communication were destroyed beyond repair. Despite the hazard attached to the mission of runner, he immediately set out to establish contact with the neighboring post of command and further establish liaison with two French batteries, visiting their position so frequently that he was mainly responsible for the accurate fire there from. While thus engaged, seven horses were shot under him and he was severely wounded. His activity under most severe fire was an important factor in checking the advance of the enemy.”

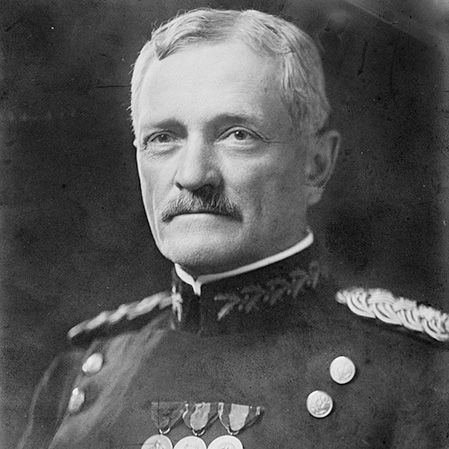

Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing personally awarded Hays the Congressional Medal of Honor. Hays completed his degree and then remained in the military for the rest of his life rising to the rank of lieutenant general and serving in World War II on the beaches of Normandy and in the Italian Alps.

Aldus Clarence Loganbill

Loganbill was born in Missouri, and the Loganbill family moved to Geary, Oklahoma, in February 1907. Two of his aunts served as Mennonite missionaries to the Cheyenne and Arapaho, and the Loganbill family wanted to be closer to them. In 1916, Loganbill traveled to Stillwater to enroll in the practical course in agriculture at Oklahoma A&M. He attended the 1916 fall semester and the 1917 spring semester. While on the wheat harvest during the summer of 1917, his parents received his draft notice. As a Mennonite conscientious objector, he requested non-combatant service and was assigned to take care of horses at Camp Travis near San Antonio, Texas.

There were four other young men from the Geary Mennonite Church in his unit. Their minister traveled from Geary periodically until he was threatened with being tarred and feathered if he returned. The objectors were not given blankets and slept on newspapers. They also suffered ridicule, intimidation and beatings from the other soldiers. The results of this treatment led to kidney problems for Loganbill. After serving 18 months, he was released from Camp Travis in the spring of 1919 and he returned home to Geary. His health never recovered and he died of kidney failure on Jan. 4, 1927. He was survived by his wife and three young children. Loganbill wasn’t listed among the former OAMC students who served their country during World War I. In Oklahoma at that time, conscientious objectors were considered slackers, cowards, disloyal and anti-American.

Loganbill was branded one of these. He didn’t request a deferment to help his father on their farm or to continue his education. Loganbill enlisted when drafted and was persecuted for doing so.

Carter Cary Hanner

Hanner had been a student two decades before the Great War. Born in Illinois, the Hanner family had moved to Stillwater in 1893 when Carter was 14. He enrolled as a student at Oklahoma A&M and then left in 1898 to enlist for the Spanish-American War. He was sent to the Philippines and served for three years. Returning to Stillwater, he joined the Oklahoma National Guard and spent some time on the U.S.-Mexico border before the United States entered World War I. After additional training, his unit sailed for France on July 4, 1918, to join the American Expeditionary Force under the command of Gen. Pershing.

On Sept. 6, he was promoted to captain and placed in command of Company E, 142nd Infantry, 36th Division on Oct. 4. Four days later, Capt. Hanner was killed on the battlefield in the Argonne Forest and later awarded the Croix de Guerre by France for his gallantry in action. Hanner was buried at the American Cemetery in Romagne, France. He was survived by his wife and three young children. The news of his death arrived only days before the announcement of the armistice ending the war.

Seven years later, the college dedicated a new men’s residence hall named in honor of Hanner. Capt. Hanner’s commanding officer and friend, Brig. Gen. Roy Hoffman, described him as “one of the best citizens, soldiers, fathers and friends I ever knew. There is not, was not, cannot be a nobler man than my dead comrade, Carter C. Hanner.”

The Aftermath

After the war, there were other changes on campus. The athletic fields for football and track, known as Lewis Field in honor of faculty member Lowery Layman Lewis, were moved to the northeast. Formerly, it had run north/south just west of where the new gymnasium and armory were constructed. Cantwell saw to it that the college assisted with the vocational retraining of disabled combat veterans under a new law from Congress. Such students each received a federal scholarship. Initially about 200 men came to the college, with more to follow over the next several years. These men and their families became staunch supporters of the institution.

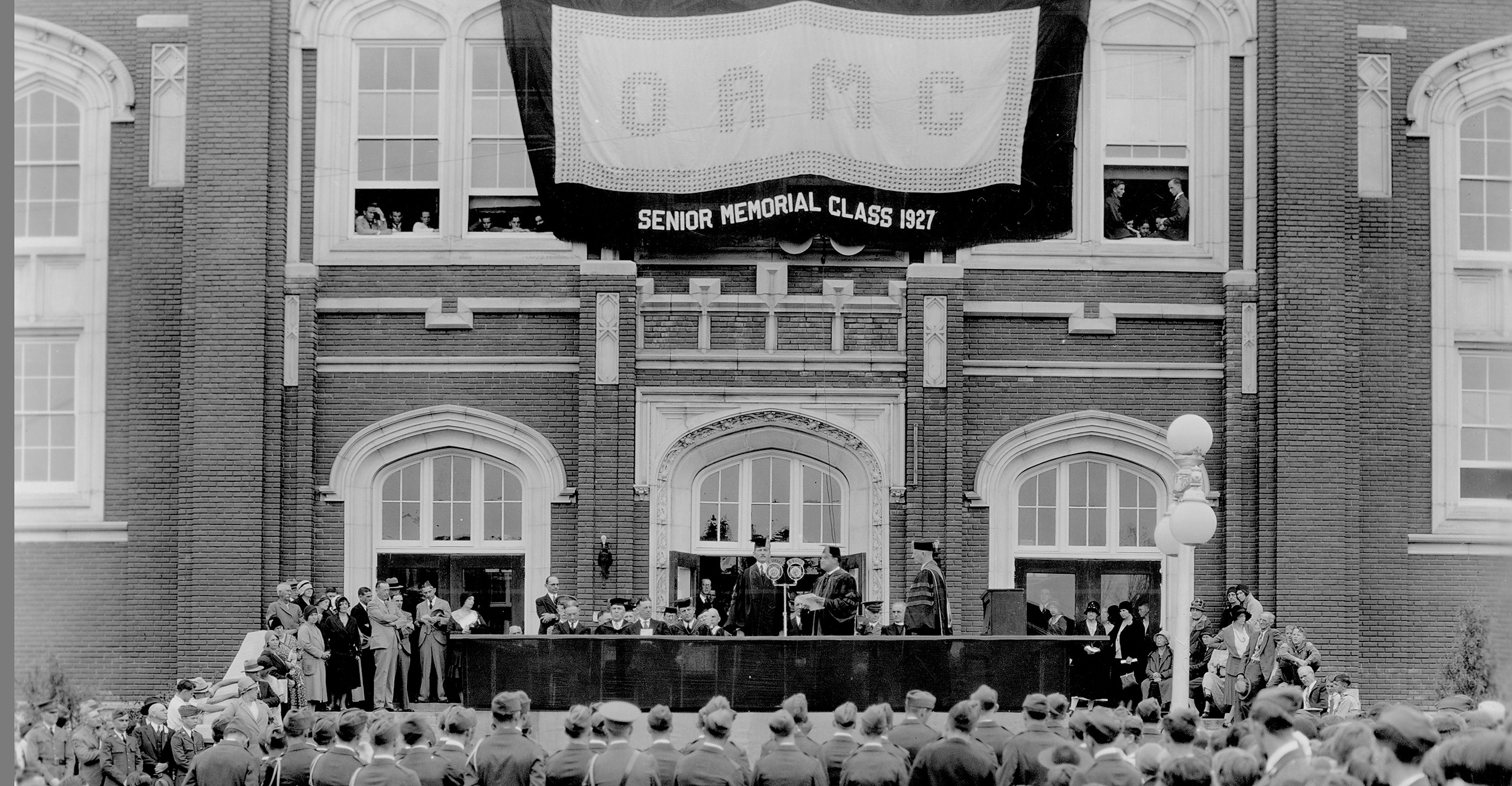

The dedication and sacrifices made during World War I were remembered throughout the years, but especially during annual Armistice Day ceremonies. Soldiers, students, families and friends gathered on campus to share expressions of gratitude for the services performed during and after the war. Many structures were proposed as memorials, but none were ever constructed. In Bennett Memorial Chapel, a plaque was placed in the entry hall listing the names of those from the Great War who lost their lives.

More stories from OAMC participants in the Great War can be found here: okla.st/WW1archives.

Photos By: OSU Archives

Story By: David C. Peters | STATE Magazine